Bulgaria's chalga pop-folk: A cultural rift

- Published

Bulgaria's sex-soaked pop-folk music culture known as chalga has come under the spotlight following the controversial decision to award EU development money to a top producer. Ina Sotirova, in Sofia, finds out why it has caused such a storm.

It is late Wednesday night at Student City, a neighbourhood notorious for its nightlife, and pop-folk superstar Andrea performs at Plazza Dance Centre. Clad in a glamorous black dress and red stilettos, she is surrounded by fans. In what has become a tradition, napkins shower over revellers and cover the floor like a thick layer of snow underneath high heels and little black dresses.

Chalga combines modern dance beats with Balkan, Gypsy and Middle Eastern rhythms. It is a cultural phenomenon - upbeat, fun and controversial - and is sweeping across the post-communist Balkans with its catchy tunes and silicone everything.

From its inception in the 1990s, pop-folk has glamorised easy money and shady deals, aggressive men and promiscuous women. Although the genre has evolved and diversified over time, its explicit lyrics and videos continue to idealise a femininity marked by an incessant sexual and material appetite, artificial looks and submissiveness.

So when word got out that European funds would subsidise Payner Media's plans for market expansion, it scandalised and polarised the country. As the leading producer and distributor of chalga and owner of three music channels on cable television, Payner is among Bulgaria's most successful businesses.

Its pop-folk empire includes not only a full arsenal of superstars, but a chain of nightclubs across the country. "It's accessible and melodic," Payner spokesman Lyubomir Kostadinov says, "a culture for the masses."

But critics have asked why Payner, which holds 80 to 90% of the Bulgarian music market, is being awarded subsidies meant for small and medium-sized business. Mr Kostadinov points out that the EU funds were meant for the technology upgrade of its TV offshoot, Planeta HD. Of the 1.6m euros (£1.4m; $2.1m) earmarked for the project, 60% was to come from the EU.

Following the outcry, the European Commission called for an investigation to inquire whether the funding decision - made in Bulgaria - met its rules.

But even before local authorities published their findings, Payner withdrew from the programme, claiming it was unable to wait for the protracted EU procedures, and would purchase the equipment independently.

'Confused values'

Yordan Mateev, editor-in-chief of Forbes Bulgaria, believes the company's decision was prompted by public pressure.

"Whether we like it or not, chalga is a legitimate business," he says.

"[Payner] would have got the money but they chose to be less hated, at the price of 1m euros."

In his view, the Payner case was an an opportunity to re-evaluate "the misguided philosophy of EU subsidies", which redistributes taxpayers' money to bureaucratically selected projects and priorities.

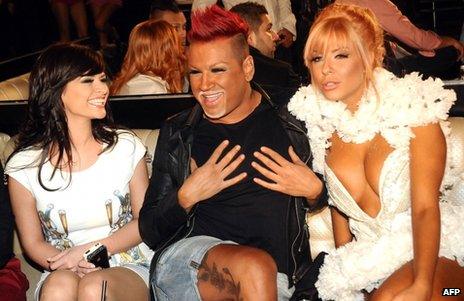

Payner Media has been promoting pop singers like these for years

Instead, it caused tensions over Bulgarian culture, morals and values, that have divided the nation for two decades, to explode. A renowned theatre director, Tedi Moskov, called for a "rebellion" against the continued popularisation of chalga, which for many symbolises everything that is low, shameful and wrong with Bulgaria's post-socialist reality.

The fall of communism was marked by a chaotic transition from a system of absolute control to the complete collapse of economic, political, social and moral structures. Back then, pop-folk music and its lifestyle were associated with the mafia-dominated nouveau-riche class that sprung out of the marriage between capitalism and lawlessness in the region's nascent democracies but, over time, it crossed over into the mainstream.

The culture has glorified the new-found "heroes of our time" says ethnomusicologist and chalga expert Ventsislav Dimov. These new identities are characterised by the "material signs of capitalist prosperity", he explains, but its "confused value system" is not a product of the industry, rather, an existing reality that chalga amplified and solidified.

Chalga everywhere

Advertising and news, politics and entertainment, and even school textbooks, according to a 2012 study, reflect the pop-folk reality, which also dictates the standards of fashion and beauty, especially among adolescents.

"It's appealing because it displays glamour and a luxurious lifestyle that are out of reach for the vast majority of people in the unstable post-communist economies," Rada Elenkova, formerly project coordinator at the Bulgarian Gender Research Foundation, says.

Bilioner is another chalga club

Even people who do not usually listen to this music - like 25-year-old Elena Ivanova - enjoy drinking and dancing to chalga on a night out with friends.

At 03:00 on Saturday night, and despite the high prices, Sin City nightclub - famous for its pop-folk parties - is packed.

"I go to these places because there isn't much elsewhere to go," Ms Ivanova says. "I don't see myself in this music. It doesn't bother me and it doesn't bring me anything, but I know people my age who compare themselves to the singers."

The ethnomusicologist, Mr Dimov, worries about this danger: "If you're born post-1990 and your life has been filled with [chalga's] dirty fairy tales, you may mistake it with reality."

Kristina Despotova, 24, is a fan, but one who holds reservations. Although she sees it as a matter of conscious choice, she realises the strong influence pop-folk culture can have on Bulgaria's youth.

"After all," she says, "we're all searching for our heroes."

- Published16 January 2013

- Published11 November 2012

- Published26 April 2012