Italy election: Rivals battle it out on and off-air

- Published

The candidates' differing characters have produced contrasting media strategies

From a media baron's on-air antics to a comedian who shuns television, the campaign strategies employed by contenders in Italy's election have been poles apart, reports the BBC's Alan Johnston in Rome.

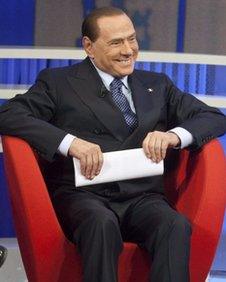

Silvio Berlusconi is in a live television studio, half out of his seat and bellowing furiously at the audience about the Communist past of his left wing opponents.

It is just one moment in a typical media performance by Italy's former Prime Minister.

He had gone into what was for him a lion's den; the Servizio Pubblico political talk show.

It airs on a channel beyond the control of Mr Berlusconi's Mediaset television empire.

Some of his sharpest critics were lying in wait for him.

Silvio Berlusconi has mainly waged his campaign from Italy's TV studios

And over more than two hours they launched attacks aimed at exposing Mr Berlusconi's many failings.

It was a chance to almost put him on trial, and the bookmakers were suggesting he might storm off the set.

But he stayed in his seat, and rose to the occasion. He twisted and turned, counter-attacked and blustered and ranted and joked and charmed.

"It became a one-man show, said Filippo Sensi, a communications expert. "He took over the broadcast."

And in the days afterwards, Mr Berlusconi's poll ratings continued to climb.

"He's shaped the history of Italian television over the last 30 years," said Mr Sensi.

"He's not someone who appears on TV: he is TV!

"It's his natural environment, his political arena. When he's on TV, he's happy - in his element."

It's hardly surprising then that Mr Berlusconi has waged his campaign for this weekend's election almost entirely from the nation's television studios.

There's been almost nothing in the way of public rallies, or moments when he might have "met the people".

Economics professor Mario Monti has not always engaged the masses effectively

"He's capable of speaking to a part of Italy that no one else seems capable of reaching," said Professor Giovanni Orsina, of Rome's LUISS University, who has written extensively on "Berlusconism"

"A part of Italy that has very little faith in the state.

"They're people who don't act politically because they don't have faith in politics."

Professor Orsina argues that these disaffected conservatives lie largely beyond the reach of newspapers and traditional party political mobilisation.

Television is the key.

And night after night Mr Berlusconi has spun his message on screens in countless Italian living rooms.

Tax bomb

You never know quite what might come next on the Berlusconi show.

Viewers who might normally flip channels when a politician appears stay tuned.

There are rows and jokes. There is political theatre. Or at least pantomime.

Pier Luigi Bersani is resolutely un-flashy

At one point during a live television discussion Mr Berlusconi picked up a big cardboard poster that was lying on the studio desk and started banging an enemy journalist on the head with it.

And he has dropped a tax bomb on his opponents.

Not only would he scrap a much-hated tax on homes. He would pay back the hundreds of euros that every Italian family was forced to pay towards it last year.

Mr Berlusconi began the campaign 15 to 20 points behind his opponents in the centre-left Partito Democratico.

But he is now reckoned to have crept up to within about 5 points of the PD.

Its leader, Pier Luigi Bersani, could hardly be more different from Mr Berlusconi.

A former Communist in his early sixties, he projects an image of down to earth, solid dependability.

He is resolutely un-flashy, and his electoral media performances have reflected his personality.

Sitting on a lead in the polls, he has defended rather than attacked.

There have been no really memorable performances.

'Tsunami tour'

Another contender, the outgoing Prime Minister, Mario Monti has certainly tried to play the campaign game, but with mixed results.

The economics professor who has led Italy's government of unelected experts for more than year is now trying to win an electoral mandate at the head of a centrist coalition.

Comedian Beppe Grillo has combined town square gatherings with social media campaigning

And this naturally remote, austere figure has sometimes looked awkward as he has attempted to engage with the masses.

Not least when he actually adopted a puppy, live on television.

"What Monti's experience has shown is that you need political skills to be a politician," said Professor Orsina.

"He's a university professor, so he's used to speaking to university students - not a very wide audience. He's stiff."

And perhaps his strongest card in government, his commanding, authoritative air, has not always come across well on the campaign trail.

"He's also basically saying I know better than you do - and this isn't particularly good in propaganda terms," said Professor Orsina.

The only campaign to have really radiated energy and enthusiasm has been conducted by the "Five Star" citizens' movement, headed by the comedian-turned politician, Beppe Grillo.

His "Tsunami Tour" has swept the length of Italy, filling piazzas with huge crowds that have gathered to hear his lacerating attacks on the traditional parties.

Mr Grillo refuses to appear on the television channels, which he regards as an integral part of the established order that has comprehensively failed the nation.

Instead his campaign has cleverly combined the use of the shiniest new social media tools with gatherings in that oldest of democratic arenas - the Mediterranean town square.

The last published polls suggest that the Five Star Movement is probably in third place, ahead of Mr Monti's coalition.