Argentina 'Dirty War' accusations haunt Pope Francis

- Published

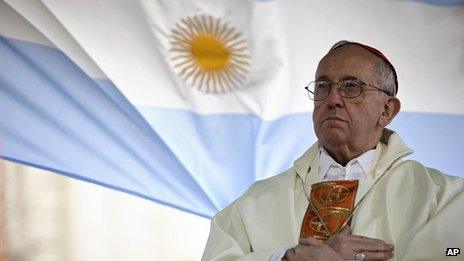

Pope Francis served as Archbishop of Buenos Aires before his accession

"I see a lot of joy and celebration for Pope Francis, but I'm living his election with a lot of pain."

These are the words of Graciela Yorio, the sister of Orlando Yorio - a priest who was kidnapped in May 1976 and tortured for five months during Argentina's last military government.

Ms Yorio accuses the then-Father Jorge Mario Bergoglio of effectively delivering her brother and fellow priest Francisco Jalics into the hands of the military authorities by declining to endorse publicly their social work in the slums of Buenos Aires, which infuriated the junta at the time.

Their kidnapping took place during a period of massive state repression of left-wing activists, union leaders and social activists which became known as the "Dirty War".

Orlando Yorio has since died. But, in a statement, Fr Jalics said on Friday he was "reconciled with the events and, for my part, consider them finished".

The Vatican has strenuously denied Pope Francis was guilty of any wrongdoing.

"There has never been a credible, concrete accusation against him," its spokesman, Fr Federico Lombardi, told reporters in Rome.

'Stolen babies'

For Estela de la Cuadra, the election of Cardinal Bergoglio as Pope, was "awful, a barbarity".

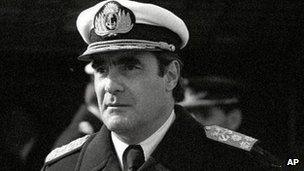

Tens of thousands of Argentines were kidnapped and killed by the military junta

Her sister Elena was "disappeared" by the military in 1978 when five-months pregnant. Their father asked Fr Bergoglio for help in finding her.

"He gave my dad a handwritten note with the name of a bishop who could give us information on our missing relatives," Ms de la Cuadra says.

"When my father met the bishop, he was informed that his granddaughter was 'now with a good family'," she adds.

In 2010, then-Cardinal Bergoglio was asked to testify in the trial over the "stolen babies" - children born to the regime's opponents who were taken and handed over to be raised in suitable military families after their mothers were killed.

The cardinal said he had only known about that practice after democracy returned to Argentina in 1983.

Ms de la Cuadra believes the handwritten note contradicts this account, and testified under oath on the subject in May 2011.

'Collaborationist'

Argentina's last military government left a deep scar on Argentine society that has still not healed.

Almost every day there is a judicial hearing where former officials are tried for human rights abuses. More than 600 have been convicted of charges including torture, the theft of babies, illegal arrests and murder.

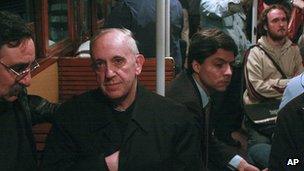

Cardinal Bergoglio, pictured on the Buenos Aires underground in 2008, was known for his humility

Pope Francis has testified twice in two separate cases, but has never been formally investigated. There is no evidence that he was in collusion with the regime.

But the actions of the Roman Catholic Church during the Dirty War are still being called into question.

In February - for the first time - the Argentine judiciary issued a ruling which stated that the Church was complicit in the abuses, and added that the Church was still refusing to investigate those believed responsible.

Pope Francis was not part of the Catholic hierarchy at the time, but he was head of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, in Argentina.

Two journalistic investigations - one in 1986, the other in 2005 - argued that the new Pope was a "collaborationist".

The first was published by a lawyer Emilio Mignone, who founded the Centre for Legal and Social Studies (CELS), an Argentine human rights NGO.

The second investigation was carried out by the current president of CELS, Horacio Verbitsky.

Both stated the view that Fr Bergoglio was close to the military.

'Tried to help'

The cardinal rarely gave interviews, but in a conversation with his biographers in 2010 he strongly rejected the allegations.

Cardinal Bergoglio told his biographers he had asked Navy chief Emilio Massera to release the priests

"On the contrary, I tried to help many people at the time," he insisted.

Alicia Oliveira, a former Argentine judge, says she has been friends with the man who became Pope Francis for 40 years.

"He was very critical of the dictatorship," she says, rejecting claims that he might have had links with the former military regime.

"He would come to my house twice a week and tell me about his concern for the priests who did social work in slums."

"When the priests were kidnapped, he met [the then head of the navy] Emilio Massera to ask for their release," Ms Oliveira adds.

Fr Yorio and Fr Jalics were eventually freed in October 1976 after suffering months of gruesome torture at the notorious Navy School of Mechanics, the main clandestine detention centre.

'No link'

The Argentine Nobel Peace prize winner, Adolfo Perez Esquivel, knows well this period of Argentine history.

He was a human rights activist at the time, and was arrested by the military in 1977. He suffered 14 months of clandestine detention and was tortured severely.

Families of Argentina's "disappeared" have long campaigned for justice

Mr Perez Esquivel told BBC Mundo: "There were some bishops who were in collusion with the military, but Bergoglio is not one of them."

A religious person himself, Mr Perez Esquivel strongly supports Pope Francis.

"He is being accused of not doing enough to get the two priests out of prison, but I know personally that there were many bishops who asked the military junta for the release of certain prisoners and were also refused."

"There is no link between [the Pope] and the dictatorship."

To be accused in Argentina of having had links with the military regime is something extremely sensitive. After all, almost 20,000 people are still listed in official documents as "disappeared", while human rights groups put the figure closer to 30,000.

Cardinal Bergoglio was never investigated as there has been no strong evidence that links him in any way to one of the darkest chapters of Argentine history.

He has certainly made no friends among members of liberal and social activist groups with his staunch rejection of issues such as gay marriage or the legalisation of abortions.

According to the Vatican's official spokesman, the accusations against Pope Francis "come from parts of the anti-clerical left".

Fr Lombardi pointed out that the Argentine justice system had "never charged him with anything".