Vatican denies Dirty War allegations against Pope

- Published

Vatican Press Secretary, Fr Tom Rosica, said the accusations must be "firmly and clearly denied" (Photo shows Pope supporters in St Peter's Square)

The Vatican has denied that Pope Francis failed to speak out against human rights abuses during military rule in his native Argentina.

"There has never been a credible, concrete accusation against him," said Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi, adding he had never been charged.

The spokesman blamed the accusations on "anti-clerical left-wing elements that are used to attack the Church".

Jorge Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, led Argentina's Jesuits under the junta.

Correspondents say that like other Latin American churchmen of the time, he had to contend, on the one hand, with a repressive right-wing regime and, on the other, a wing of his Church leaning towards political activism on the left.

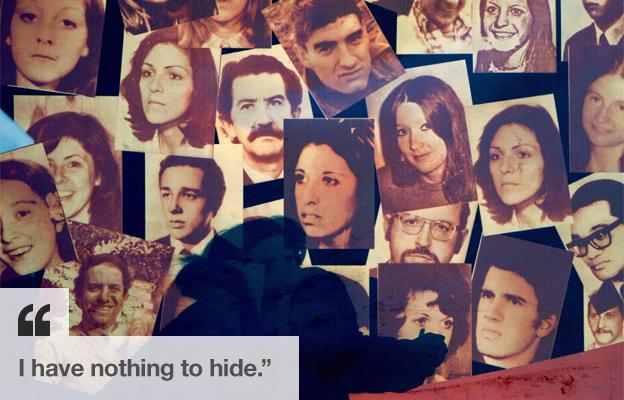

One allegation concerns the abduction in 1976 of two Jesuits by Argentina's military government, suspicious of their work among slum-dwellers.

As the priests' provincial superior at the time, Jorge Bergoglio was accused by some of having failed to shield them from arrest - a charge his office flatly denied.

Judges investigating the arrest and torture of the two men - who were freed after five months - questioned Cardinal Bergoglio as a witness in 2010.

The new Pope's official biographer, Sergio Rubin, argues that the Jesuit leader "took extraordinary, behind-the-scenes action to save them".

Another accusation levelled against him from the Dirty War era is that he failed to follow up a request to help find the baby of a woman kidnapped when five months' pregnant and killed in 1977. It is believed the baby was illegally adopted.

The cardinal testified in 2010 that he had not known about baby thefts until well after the junta fell - a claim relatives dispute.

Turned in?

In his book The Silence, Argentine investigative journalist Horacio Verbitsky says the Jesuit leader withdrew his order's protection from Francisco Jalics and Orlando Yorio after the two priests refused to stop visiting slums.

The journalist is close to Argentine President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who often clashed with Cardinal Bergoglio on social policy.

"He turned priests in during the dictatorship," Verbitsky was quoted as saying by Reuters news agency.

The man who is now Pope once talked about the two priests to his biographer.

"I warned them to be very careful," he told Rubin. "They were too exposed to the paranoia of the witch hunt. Because they stayed in the barrio, Yorio and Jalics were kidnapped.''

Both priests were held inside the feared Navy Mechanics School prison. Finally, drugged and blindfolded, they were left in a field by a helicopter.

Orlando Yorio, who reportedly accused Fr Bergoglio of effectively delivering them to the death squads by declining to publicly endorse their work, is now dead.

AP news agency quoted Francisco Jalics as saying on Friday: "It was only years later that we had the opportunity to talk with Fr Bergoglio... to discuss the events.

"Following that, we celebrated Mass publicly together and hugged solemnly. I am reconciled to the events and consider the matter to be closed."

Adolfo Perez Esquivel, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for defending human rights during the dictatorship, believes Fr Bergoglio "tried to... help where he could" under the junta.

"It's true that he didn't do what very few bishops did in terms of defending the human rights cause, but it's not right to accuse him of being an accomplice," he told Reuters.

"Bergoglio never turned anyone in, neither was he an accomplice of the dictatorship," Mr Esquivel said.

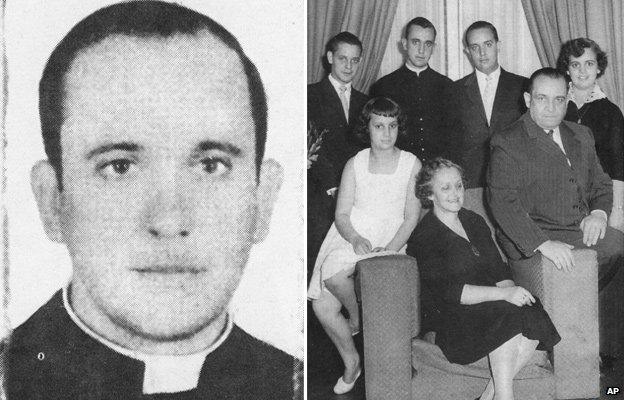

From a humble background in Argentina, Jorge Mario Bergoglio has risen to the head of the Roman Catholic Church as Pope Francis. We look at key moments in his life and career so far.

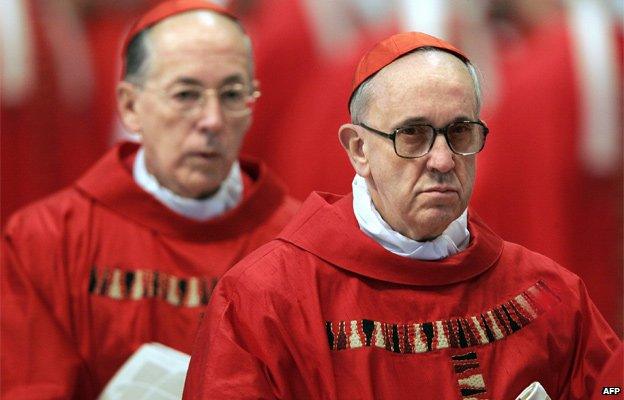

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born on 17 December 1936 in Buenos Aires. His father was an Italian immigrant railway worker. He became a Jesuit priest at 32, a decade after losing a lung due to illness and abandoning his chemistry studies. He became a bishop in 1992 and was made Archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1998.

1970s: Human rights groups have raised questions about his role under the Argentine military dictatorship of 1976-1983 - and particularly about the kidnap of two Jesuit priests. The cardinal's office has always denied his involvement. He told Perfil magazine in 2010 he had helped some dissidents escape the country.

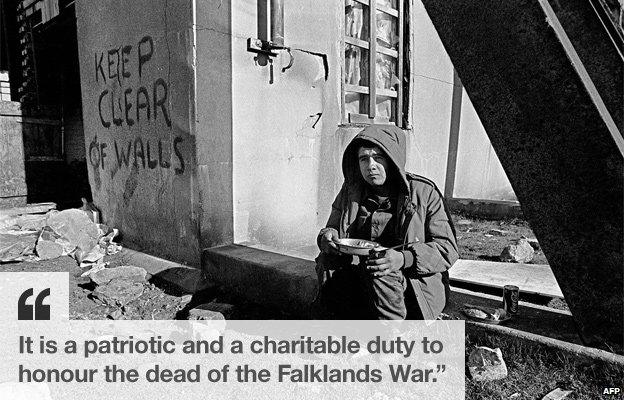

1982: Pope Francis has been a strong supporter of the veterans of the war in the Falkland Islands - referred to in Argentina as Las Malvinas. He has spoken against attempts to "demalvinizar" or gloss over the history of the war.

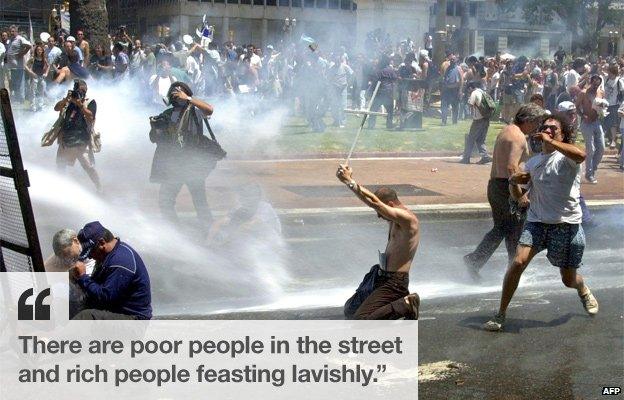

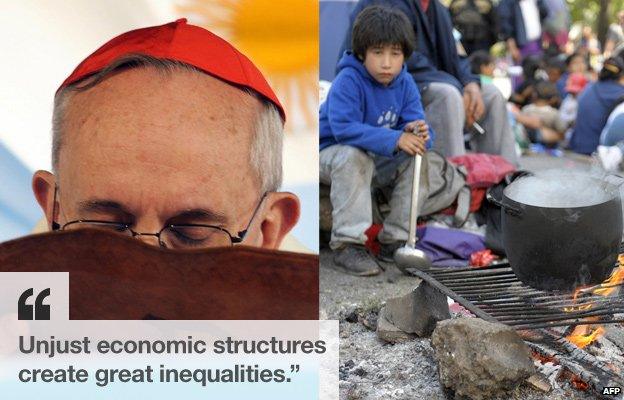

2001: The Archbishop of Buenos Aires became a cardinal in 2001, as the Argentine economy was in crisis. Speaking in Buenos Aires as thousands joined rallies against government austerity plans, he highlighted the contrast between the rich and "poor people who are persecuted for demanding work".

2005: Cardinal Bergoglio was seen as a strong contender to become Pope at the 2005 conclave to elect a successor to Pope John Paul II. He was reported to be the chief rival to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who was duly elected and became Pope Benedict XVI.

2009: As cardinal and archbishop, he stood out for his humility, living in a modest apartment, rather than his luxury official residence. In his sermons, he often stressed social inclusion and criticised governments which did not help those on the margins of society, describing poverty in Argentina as "immoral and unjust".

2010: Although Pope Francis is strong on social justice, he is extremely conservative on sexual matters. He voiced staunch opposition to gay marriage when it was legalised in Argentina in 2010. He said: "Let's not be naive: this isn't a simple political fight, it is a destructive attack on God's plan."

2012: Cardinal Bergoglio preferred life outside the bureaucracy of Rome and he criticised those "who clericalise the Church". In a sermon to Argentine priests, he attacked those who would not baptise children of single mothers. "Those who separate the people of God from salvation. These are today's hypocrites."

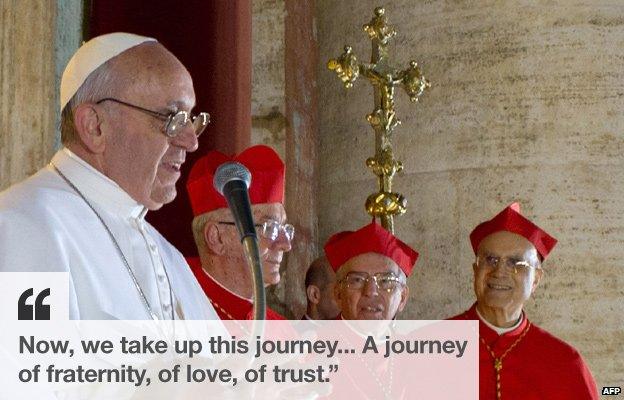

2013: Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio was not seen by the media as one of the front-runners to succeed Pope Benedict. But he is now the first non-European Pope for more than 1,000 years and the first from Latin America, home to 40% of the world's Catholics.