EU leaders gamble in Cyprus bank bailout

- Published

- comments

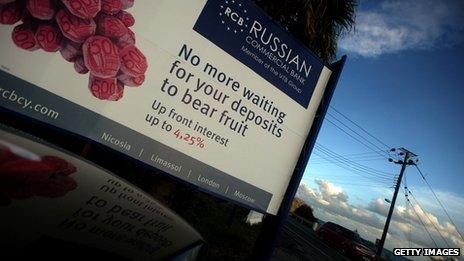

Half the money in Cypriot banks is thought to be Russian - much of it laundered

Once again - faced with a crisis - Europe's leaders have gambled.

As part of a bailout deal for the island of Cyprus they have decided to impose a tax on savers. It has not been done before in the eurozone crisis, its legality may be questioned and the risks and consequences are unknown. Savers with deposits of over 100,000 euros ($130,000, £86,000) will face a one-off tax of 9.9%. For those with less funds in their accounts the tax will be 6.5%.

This was the price for a 10bn-euro bailout. Without it Cyprus risked defaulting by May.

The Germans, however, were not prepared to support a larger bailout. They suspected that half of the deposits in the island's banks were held by Russians with much of the money being laundered. Rescuing high-rolling Russians could not be sold to German taxpayers.

But there are an estimated 25,000 British residents in Cyprus. Many of them have bank accounts in Cypriot banks. There are 3,500 British troops stationed there with savings in Cypriot banks. It is estimated that British savers have 2bn euros on deposit. They too will see their funds taxed - although Chancellor George Osborne has said he will compensate UK government employees and service personnel.

It shows how sensitive this issue is that the UK government has taken this action. There will be those who say that the government is indirectly funding a eurozone bailout.

Monday is a holiday in Cyprus and the banks won't re-open until Tuesday. Already savers have been trying to withdraw their funds. Although it will be too late to avoid the tax, the banks are expecting a difficult day on Tuesday.

Poor forecasts

The EU commission has said this has no implication for banks in Spain and Italy but a message has been sent. For the first time in an EU state - during this crisis - deposits are being seized.

There are plenty of voices saying this poses a threat to the Cypriot economy. Fiona Mullen, an economic analyst, predicts "the damage will be long lasting. Business and financial services were the only sectors generating jobs and tax revenue."'

Sharon Bowles, who chairs the European Parliament's Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee is appalled. "This grabbing of ordinary depositors's money is billed as a tax," she said, "so as to try and circumvent the EU's deposit guarantee laws. It robs smaller investors of the protection they were promised."

The EU has a poor record in predicting the consequences of its bailouts. Time and again it has under-estimated the impact of austerity. Even though the Cypriot economy is tiny - what will be the impact of this on its GDP? How will the bailout loan be re-paid, or will Cyprus - like Greece, Spain and Portugal - end up facing years of hardship?

Portugal should give the EU Commissioners pause for thought. Only five months ago the prediction was that the economy would shrink by 1% this year. Now the prediction is that it will contract by 2.3%. So its bailout terms have been eased.

Greece is struggling to meet the conditions of its second bailout. There is already a shortfall in the revenue that was supposed to be collected. The governing coalition is fragile and may not survive the year.

Italy is in a volatile mood, facing months without a stable government.

No wonder the former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti sent a four page letter to other EU leaders warning that "public support for the reforms, and worse for the European Union, is dramatically declining."

At last week's anti-austerity protests in Brussels Bernadette Segol, the General Secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation, said "the doubt about the benefits of the EU is showing more and more...the burden is being put on the people."

Eurozone finance ministers and EU officials have gambled again. Have they saved a small country from bankruptcy and applied a Band-Aid to yet another crisis or have they sent a dangerous message to savers elsewhere?