The struggle for Cyprus

- Published

- comments

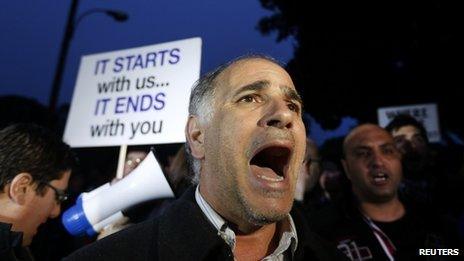

Bank employees are among those protesting outside the parliament in Nicosia

There is a fierce struggle going on between the elected government of Cyprus on one side and Germany and European officials on the other.

The tension is not disguised. Many Cypriot MPs believe they are being blackmailed into doing what the eurozone wants.

European officials are furious. They say the troika (the EU, the IMF and the ECB) has been ignored. They resent the fact that Cyprus turned to Moscow before Brussels this week.

Cyprus has been given a deadline by the European Central Bank (ECB): agree a bailout programme with the eurozone and IMF by Monday or funding for the banks will be withdrawn. The consequence would be the collapse of the banking sector and a possible exit from the euro. This is brutal power politics.

Difficult choices

The Cypriot government is racing against the clock to come up with a plan which will raise sufficient funds for the country to qualify for an EU/IMF bailout. Some of the details are known:

1. Restructuring the banks: Under this plan the Laiki (or Popular) Bank would be split into a "good" and "bad" bank. Deposits under 100,000 euros (£85,269) would be protected in the "good" bank. Larger deposits would be placed in the "bad" bank and would take substantial losses. The Germans favour this idea and want to see larger depositors share in the cost of saving Cyprus.

2. Investment fund: The government wants to set up an investment fund which investors - perhaps Russia - can buy into. The plan is to put pension funds, Church assets and money from future gas reserves into the fund. The Germans are unconvinced by this plan and Chancellor Angela Merkel indicated today that nationalising pension schemes as a way of raising money was not acceptable.

3. Transactions: There would be controls on bank transactions to stop a run on the banks with money being taken out of Cyprus.

The target is to raise 5.8bn euros ($7.5bn; £4.9bn) and so qualify for a 10bn-euro rescue loan from the EU/IMF.

The underlying tension remains. The Germans want large investors - many of them Russians - to share in the cost of bailing out Cyprus. They want the Cypriot banking sector scaled back. The Cypriots are desperate to protect their financial sector, which is so important to the island's economy. If large depositors are hit hard the fear is that the financial industry will be destroyed.

Many Cypriots believe that is precisely what Brussels wants.

Legacy of bitterness

The Europeans believe that no plan is workable unless large depositors face a tax of at least 9.9% on their accounts. Under all the current plans those bank customers with accounts holding less than 100,000 euros will be spared.

Whatever the outcome the legacy will be one of bitterness. I have seen anti-German posters and heard anti-German rhetoric in Greece, Spain, Italy and Portugal. But never has it been so open as in Cyprus. And that resentment extends to the EU. "They've brought us to the brink," said one bank worker this morning, "the Europeans wanted to destroy our economy and they've done it".

Even if the Germans are right - and the Cypriot banking sector needs cutting in half - they are perceived as bullying outsiders.

This crisis has revealed yet again the faultline at the heart of the euro. Economic and monetary union has yoked together very different economies and cultures.

The stress of trying to blend them together is putting the European project under severe strain. Some economies are in a depression and the political fallout from this still lies ahead.