How Greece's once-mighty Pasok party fell from grace

- Published

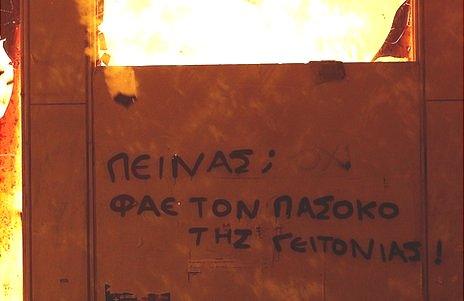

"Hungry? Eat your local Pasok politician" - a message scrawled on a building set ablaze during anti-austerity riots in Athens in 2012

The endless empty rows said it all. For a political party struggling to survive, the choice of a huge Athens stadium for its annual congress was probably a bad one.

A few thousand loyal supporters gathered, but the tens of thousands of vacant seats spoke of a party nearing oblivion.

The Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok) has dominated the Greek political scene for more than three decades. It soared to power in 1981. The dictatorship had just ended here; Pasok created a welfare state, transforming Greece into a modern, European country.

But today it languishes at around 6% in the polls, widely reviled for corruption and for accepting hated austerity while in power in 2009. At the congress, it still inspires some loyal supporters.

"The party has been misrepresented," says Panagiotis Alamanas. "Any government would have had to cut wages and pensions. Everyone is trying to accuse Pasok of all the mistakes Greece made in the past 40 years."

"It is really difficult to explain to someone today that you support Pasok," admits Marina Mithou, a student. "It's like a dirty word. But we will try to revive it."

'Love affair'

For now Pasok is on life support as part of the coalition government. But few expect it can truly rise again. At its height, it was backed by almost half the Greek electorate under the adored leadership of Andreas Papandreou.

"He was a genius," recalls Sifis Valirakis, one of the founding members. "Pasok was a love affair. It was about a dream of freedom, democracy and a better future."

The 70-year-old pauses, his smile fading. "But I feel a little disappointed, because the dream was not realised as we expected. We have a country bankrupt, corrupt and not functioning as it should."

Is Pasok to blame, I ask?

"Among others, yes. It is no longer the party we fell in love with."

Pasok modernised Greece, enriched it, but then mismanaged it. The country racked up vast debts while Pasok and the centre-right New Democracy alternated in power. Both parties have been shaken by corruption and clientelism.

"Pasok isn't to blame for everything that went wrong here," says political commentator Pavlos Tsimas, "but being the natural party of government for over three decades, it is now being punished".

The party is criticised for sowing the seeds of future problems by building a bloated public sector based on patronage. Tens of thousands of jobs were created in state companies and then given to Pasok members: a system that continued under New Democracy.

The notion of meritocracy was pushed aside as senior positions in universities and local councils became party appointees. Public construction licences were often decided on the basis of political support, with MPs lining their pockets through kickbacks. Corruption blossomed - even Andreas Papandreou himself went on trial in 1991 accused of embezzlement. He was narrowly acquitted.

But Pavlos Tsimas says that the investment Pasok made in the country was essential, despite the extravagant way it was handled.

'Shock'

A statue of George Papandreou senior stands in Kalentzi

"When Pasok took over, Greece was not a European state," he says. "It had no public services to speak of. Pasok installed the national health system and free education. So it was a shock to its voters when the party of the welfare state suddenly said it was cutting pensions, salaries and jobs."

The collapse of Pasok has gone hand-in-hand with the decline of the Greece it created. And with it has fallen the once omnipotent Papandreou dynasty: George senior, Andreas and George junior were all prime ministers here, the former leading a party that preceded Pasok. Nepotism has long had a grip on Greek politics.

But in their family village of Kalentzi in the Peloponnese, the name is still held high. The tiny community of 600 people nestles in the mountains, overlooking a lush valley. In George Papandreou Square, an iron statue of Andreas faces another of his father, George senior.

The Papandreou home has become a cafe. Inside, I meet a cousin, Vasilis Stavropoulos. "The Papandreous are a great political family," he says proudly. "But perhaps democracy shouldn't be about dynasties."

Maria Leventi remembers the Papandreous fondly. "All of them are beloved here," she tells me, "because they gave us a better life when we were poor. They gave us the money to buy food and clothes. We could buy four televisions for one house, four cars for one family," she adds with a smile.

Did they make Greece feel richer than it actually was, I ask?

"Yes - a little," she confesses.

'Corpse'

So what is replacing Pasok's Social Democracy? The answer is clear in nearby Patras. The city was always a party stronghold. But in last year's election, it ditched Pasok for the first time, backing the new anti-bailout leftists, Syriza. Its leader is often compared to Andreas Papandreou for his firebrand rhetoric.

Alexandros Liakopoulos and his family were among those who switched sides. Former staunch Pasok supporters, they are now suffering as many Greeks are, with two family members out of work and his mother's pension slashed by 60%.

"Now the party has destroyed our national identity, our social and business environment. It has destroyed everything," Alexandros says.

Would the Liakopoulos family ever return to Pasok?

"Of course not. It's a corpse."

One of Europe's leading left-wing parties has fallen far. Its destiny has been tied to that of Greece: a confident European nation that has now lost its way.

Pasok dreamed of a different legacy, to be remembered for its considerable early achievements. But instead it has become the political victim of a crisis it helped create. And one which might bring it down for good.

- Published29 January 2013

- Published28 June 2023