Europe and Baroness Thatcher: The great divide

- Published

Over the years, Margaret Thatcher became viscerally opposed to handing over more sovereignty to Europe

Europe's leaders both resented her and admired her. Francois Mitterrand said she had "the eyes of Caligula and the mouth of Marilyn Monroe".

Another French President Jacques Chirac said: "She was one of the most feared figures on the international stage."

He went on to say: "What made her great in my view was above all her conviction... She never doubted being in the right."

At the same time he once asked about Margaret Thatcher: "What does she want from me, this housewife? My balls on a plate?"

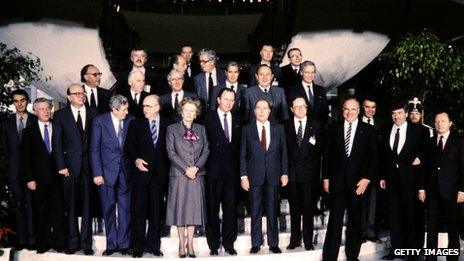

The caricature of Margaret Thatcher was of a UK prime minister constantly "hand-bagging" other European leaders.

The story was often told of her attending a summit in 1984, banging the table, and demanding: "I want my money back."

She fought fiercely for a British rebate, but she actually said: "We are simply asking to have our own money back."

'Greatest folly'

There were, however, many sides to Margaret Thatcher's relationship with Europe.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, she was opposed to German reunification. Helmut Kohl, the German chancellor at the time, recalls her saying: "We beat the Germans twice and now they're back."

In time she understood that Germany could not remain divided and supported the need to embed the new Germany inside Europe and its institutions.

She became a strong supporter of eastern and central European countries joining the European Union.

So today the current German Chancellor Angela Merkel recalled her as "one of the greatest leaders in world politics of her time. The freedom of the individual was at the centre of her beliefs so she recognised very early the power of the movements for freedom in Eastern Europe... I will never forget her contribution in overcoming Europe's division and the end of the Cold War."

Margaret Thatcher was a strong supporter of the single market in Europe and signed the Single European Act.

Her critics say that she saw the benefits of an open market but failed to appreciate that the management of that market would inevitably lead to handing over of some sovereignty.

What she opposed was using the single market as a stepping stone to closer political union.

In her keynote speech on Europe, delivered in Bruges in September 1988, she said: "We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level with a European super-state exercising new dominance from Brussels."

That became the great divide.

Many of Europe's leaders were committed to closer integration. They believed in it, with the single market but a staging post.

Margaret Thatcher became viscerally opposed to handing over more sovereignty. In her book Statecraft, she described the European Union as "perhaps the greatest folly of the modern era".

The former Czech President Vaclav Klaus - and an avowed Thatcherite - said: "Many of us will never forget her famous speech in Bruges, where she clearly said that the suppression of nation states and the concentration of power in Brussels will destroy Europe."

It was her rejection of further integration at an EU summit in Rome that prompted a rebellion and resignations within her own cabinet and led eventually to her downfall.

Divisions over Europe to this day have become embedded in the Tory party.

Conviction politician

On the whole, Europe's leaders have been warm with their tributes.

Ex-French President Jacques Chirac said of Lady Thatcher that "she never doubted being in the right"

French President Francois Hollande described her as "a great figure who left a profound mark on the history of her country".

The president of the European Commission, Jose Manuel Barroso, described her as a "circumspect yet engaged player in the EU".

But he also added: "Her legacy has done much to shape the United Kingdom as we know it today, including the special role of the UK in the European Union that endures to this day."

Britain's current ambivalence towards the EU is part of Margaret Thatcher's legacy: the totemic role of the rebate; the insistence on opt-outs; the belief in British exceptionalism; the profound unease at power slipping away to a bureaucracy in Brussels.

Britain has never committed to the idea of Europe. It is indifferent to the dream of ever-closer union. It fears the weakening of its own power as more and more decisions are taken at a European level in Brussels.

European officials recognise that it was Margaret Thatcher who shaped many of the UK's instincts towards Europe.

They learnt early that Lady Thatcher was a conviction politician. She approached every meeting or summit with passionate intensity.

Europe's leaders had built their project on compromise, on trade-offs, on bargaining. The first British woman prime minister came from a very different tradition; arguments were to be won.