How Croatia and Serbia buried the hatchet

- Published

Serbian guns fire on Croatian targets during the 1991 conflict between Croatia and Serbs

In 1991 Croatia was in flames. Montenegrin troops from the Yugoslav army were bombarding the historic city of Dubrovnik and, with its backing, rebel Croatian Serbs were carving out one-third of the country.

One day, the rebel Serbs hoped, the areas of Croatia they controlled would become part of a Greater Serbia.

The following year Croatia was helping Bosnian Croats fight Bosnian Serbs and later Muslim Bosniaks.

The Yugoslav wars cost tens of thousands of lives and made refugees of millions.

A tale of two pictures

And yet today, the region has been transformed and on 1 July Croatia will enter the European Union.

Symbolic of the change perhaps are two photos, which have been in the Balkan press and on social media recently.

One shows a happy-looking pair travelling together on a coach. They are Croatian Foreign Minister Vesna Pusic and her opposite number from neighbouring Montenegro, Igor Luksic.

They were both in London on their way to the funeral of Lady Thatcher.

The second picture shows a young couple kissing, external. The boy is draped in a Serbian flag and his girlfriend in a Croatian one. The photo was taken in Mostar, in Bosnia-Hercegovina, during a school parade.

The story is that the Croatian girl was allegedly berated by an old woman for having a Serbian boyfriend. This prompted her to turn and kiss him.

Two images that have sparked interest and comment in the Balkans

Both pictures say a lot about how far Croatia, Croats and their neighbours have come since the end of the wars in Croatia and Bosnia in 1995.

Apology

Today, while no one has forgotten the enthusiastic participation of Montenegrin troops in the attack on Dubrovnik, relations with Croatia could not be better.

In 2000, Milo Djukanovic, Montenegro's prime minister during the Dubrovnik campaign, apologised. In 2005, compensation was paid for stolen cows. A dispute over a maritime boundary remains to be settled, but is not a major issue of discord.

When it comes to Serbs and Bosnians, relations are more complicated.

Mostar in southern Bosnia, is a town where Serbs, Croats and Muslim Bosniaks all lived before the war.

When the Bosnian war broke out in 1992, Croats and Bosniaks first fought the Serbs here and then Croats fought Bosniaks, with the occasional help of the Serbs.

The kiss picture has elicited mixed reactions. Some were enthusiastic, seeing it as symbolic of young people leaving the past behind. Others were more sceptical.

In a way both were right.

Croatia's relationship with Serbs and Serbia has been long and tortuous. The two languages are very close. Croats are mostly Catholics though and Serbs are Orthodox. Croats write with the Latin alphabet. Serbs use both that and Cyrillic.

A role for Serbs

Since 1995, however, relations between Serbs and Croats have been transformed beyond recognition, and for the better.

Yet a new survey of young Croats shows a relatively high level of antipathy towards Serbs.

In 1991, just before the war, Serbs were 12.2% of the population of Croatia. Now they number a third of that proportion, around 4.3%.

Areas such as the former breakaway region of Krajina, from where Serbs fled or were ethnically cleansed in 1995, remain depopulated, as few returned after the war.

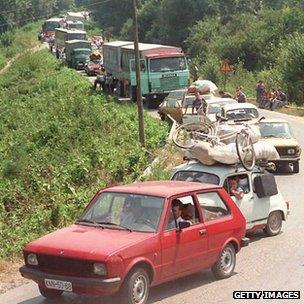

Thousands of Serbs fled from Croatia after Croat troops retook breakaway areas

According to Prof Tvrtko Jakovina, a historian and member of the Croatian president's Foreign Policy Council, many Croats would say privately, "probably we are better off like that".

The reason is that without a substantial minority of Serbs many Croats feel more secure and have less reason to fear a new conflict.

But Prof Jakovina notes that, at the same time, Serbs in Croatia now play a significant role.

In the last government a Serbian party was part of the ruling coalition, while today several Serbs are ministers or in prominent roles.

Croatian businesses are also investing heavily in Serbia, though Serbs complain that it is harder for their companies to break into Croatia.

Croatian music is popular in Serbia, and Serbs have returned to holiday in Croatia, though they are always nervous that a disgruntled person will vandalise their car, identifiable by its Serbian number plate.

Friends again

From 2004 until last year, when President Boris Tadic, who came to power promising reform, was at the helm, relations between the two former enemies flourished.

But at the same time, there were difficult moments.

Both Croatia and Serbia have lodged cases at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, accusing each other of genocide. Neither has come to court yet.

Last year relations chilled when the new Serbian President, Tomislav Nikolic, formerly an extreme nationalist, said that Croats should not return to the town of Croatian town of Vukovar, which was virtually levelled by Serb and Yugoslav forces in 1991. He said it was a Serbian town.

Then, last November, two Croatian generals charged with ethnic cleansing of Serbs from Croatia in 1995 were acquitted by the UN's Yugoslav war crimes tribunal in The Hague.

Croats were triumphant, Serbs embittered. It became fashionable to talk of a new "ice age" in relations.

But it did not happen.

Today, despite tensions, the trend is upwards towards more co-operation, not downwards towards conflict.

Milan Pajevic, the director of the Serbian government's European Integration Office, says his Croatian counterparts are offering to help Serbia with its application to join the EU.

They are "very motivated to help us" and "on the working level, relations are just fantastic", he says.

Football tensions

It is clear though that relations depend on the circumstances.

Recently Serb fans were barred from attending a Serbia-Croatia World Cup qualifier match in Zagreb, for fear of violence.

The Croatian fans then booed the Serbian national anthem and some chanted "Kill a Serb!" during the match.

Also, Croatia's nationalist right has mobilised demonstrations against the recent erection of Serbian Cyrillic road signs in Vukovar, where many Serbs still live.

Happier times: Stipe Mesic (right), Croatia's president until 2010, with Montenegro PM Milo Djukanovic

Croatia's relations with Bosnia-Hercegovina are also complicated.

Virtually all Bosnian Croats, who account for perhaps 14% of the population, hold Croatian citizenship, as do many others who can claim a Croatian link. This means that when Croatia joins the EU they will be EU citizens, while most others in Bosnia will not.

Bosnia's Croats have always voted in Croatian elections, but in recent years there has been a growing political estrangement with Croatia, whose leadership during the Bosnian war sought to create an effective Greater Croatia.

Since 2000, Croatia has cut funding for their institutions and made it harder for them to vote. The so-called nationalist "Hercegovinian lobby" is now far less influential in Croatia than it used to be.

Stability

Progress has been made in resolving some outstanding issues between Croatia and Bosnia, but some problems Croats are at a loss to help with.

As Bosnians cannot agree amongst themselves over sanitary and veterinary certification, their exports of meat and dairy produce to the EU, which in this case means mostly Croatia, will cease on 1 July when it enters the EU.

The export issue, quite apart from questions about the future of the Croats in Bosnia, has left most Croats and not least the government at a loss.

"It's so complicated that no one really knows what to do," says Prof Jankovic.

When Croatia joins the EU a new line, that of the Union's external border, will change the Balkan map.

But, as Mrs Pusic put it in a recent interview, that does not mean that Croatia will have less to do with its former Yugoslav neighbours.

"The way I see it," she says, "yes, we are entering the EU but we are not moving anywhere. Look at the geography and demographics.

"Our stability depends on the stability of the region and that depends on our capacity to contribute and we can contribute to the stability of our region. That is our European task."