Poverty in Bulgaria drives more to make ultimate sacrifice

- Published

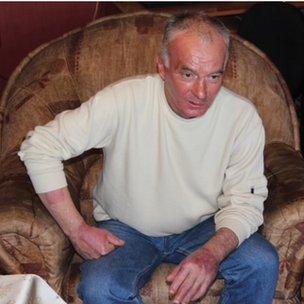

Dmitar Dimitrov says he set himself on fire for the sake of his people

In Bulgaria, six people have burned themselves alive in protest at worsening poverty levels since the start of the year. Ahead of parliamentary elections this weekend, the BBC's Tom Esslemont meets some of those affected.

Dimitar Dimitrov did not just want to die. He wanted to sacrifice himself for his country.

On 13 March, the unemployed 53-year-old set off from his apartment in the capital, Sofia, and headed for the presidential offices in the city centre.

When he arrived, he doused himself in petrol and set himself alight.

Presidential guards rushed to put out the flames.

After three weeks in hospital and a number of operations to repair his face and limbs, he is home and telling the tale.

"It was excruciating. People who have had minor burns will know how bad that pain is," he says. "But they don't know what it is like when your whole body, your flesh, is on fire. Now I realise why the church used to burn people at the stake."

Mr Dimitrov still bears the scars. He has several large blisters and the skin on his arms is patchy from the skin grafts used to repair his face.

His protest happened weeks after thousands of Bulgarians took to the streets, demanding an end to falling wages and rising energy bills.

The demonstrations led to the resignation of the centre-right Prime Minister, Boiko Borisov.

Mr Dimitrov wanted the world to understand the predicament of the EU's poorest member.

He sees what he did not just as a protest against his own drop in salary, but also as a moment of self-sacrifice for his compatriots.

Tens of thousands of Bulgarians joined protest rallies in March

"I believe I achieved what I set out to achieve. I might have been a fool, but I hope it will change things for the better here," he says.

Mr Dimitrov is not alone.

Rampant unemployment

Drive two-and-a-half hours east from Sofia and you get to the town of Radnevo.

Rows of concrete apartment blocks welcome you, transporting you back to Bulgaria's communist era.

Visually, this town has changed little in the two-and-a-half decades since independence. Coal mining and manufacturing provide some of the few jobs going. Unemployment is rampant. Officially, the national figure is close to 12%. Some analysts say the real tally is much higher.

Roma are the poorest community in Bulgaria

Here, trust in regional and national government has largely broken down.

Vechislav Arsenov, from Radnevo, was 53 and unemployed the day he set fire to himself.

Handouts from the local authority were drying up.

On the day he died, Vechislav Arsenov rang each of his five grown-up children to tell them he was sorry for what he was about to do.

Then he went to the mayor's office to ask for money. He insisted that the mayor come and talk to him, shouting to the receptionists that, if no such meeting were granted, he would light a match.

Hero

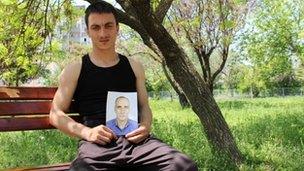

"We were desperate," his son, Txumir, explains. "My father had recently lost his job. We could not pay our bills or our debts and he could not afford to buy food for us."

Txumir is now trying to keep his impoverished family alive. He, too, is unemployed and relies on summer work as an agricultural labourer.

Eleven of the family (six children and five adults) share Txumir's two-bedroom flat.

Txumir Arsenov remembers his father, Vechislav

He used to be angry with his father, but now he says he feels his protest was heroic.

National tributes were paid to him and the four other Bulgarians who have died, since January, by burning themselves.

One of them, Trayan Marechkov, was 26. Another, Plamen Goranov, a mountain climber and photographer, was 36.

But what do politicians make of this disturbing pattern of self-harm and suicide?

I asked Boiko Borisov who, two months after resigning, is running for parliament once again and hopes to be re-elected prime minister.

He is proud of his first term, taking credit for a string of building projects his government completed, including a metro line in Sofia and a new road connecting the capital with the Black Sea.

Prime Minister Boiko Borisov announced his government's resignation on February 20, 2013.

He does not not want to dwell on the subjects of poverty and protest.

"We already had a day of grief for the victims of self-immolation. We are very sorry for the people, but changing Bulgaria cannot be done in the space of a few weeks," he says.

"During my time in office we have successfully built several new infrastructure projects. I believe these help stabilise our economy."

Voice of the people?

Back in Dimitar Dimitrov's apartment on the outskirts of Sofia, the evening television news is on.

A glamorous woman introduces items on the election and the economy. A few weeks ago, as he lay recovering in hospital, Mr Dimitrov was the main story.

"I never thought there would be so much media attention," he says.

"Now I see that, having survived setting myself on fire, I can be the voice of those experiencing what I have experienced. I hope that by telling my story I can make more people aware of the situation here in Bulgaria."

Back home with his wife and daughter, Mr Dimitrov hopes to return to work as a blacksmith.

Weary of earning the lowest wages in the EU, Bulgarian people are hoping whoever wins this weekend's election will put an end to the misery that has tipped those like him over the edge.

- Published8 May 2013

- Published13 March 2013

- Published13 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013