Clock ticks on Swiss banking secrecy

- Published

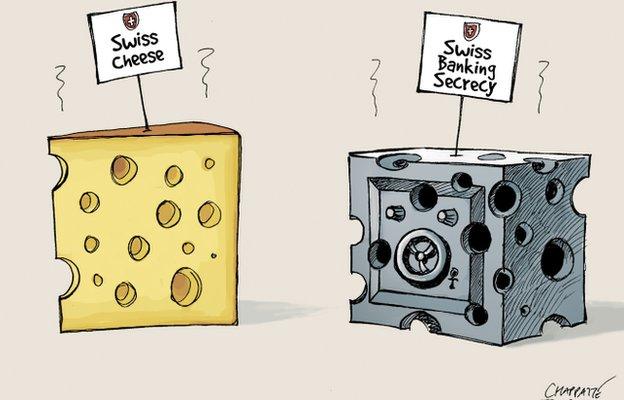

Many Swiss believe banking secrecy cannot be sustained (Chappatte in NZZ am Sonntag, Zurich - www.globecartoon.com)

Switzerland is facing mounting pressure finally to abandon its long tradition of banking secrecy. The United States has already told the Swiss government it expects Swiss banks to provide the US authorities with automatic information about US clients.

Now the European Union is demanding the automatic exchange of information too, a policy non-EU-member Switzerland will have difficulty avoiding if it wants access to Europe's financial markets.

But giving up banking secrecy is likely to be a painful process for the Swiss. While other countries see the practice as a way to hide the ill-gotten profits of crime, corruption, or tax evasion, in Switzerland it is viewed as an honourable policy which illustrates the relation of trust between state and citizen.

"The origin of Swiss banking secrecy... is really a professional secrecy like that of a doctor or a lawyer," explains Michel DeRobert, head of the Association of Swiss Private Bankers.

"He is not supposed to give out the data of his clients, he's not supposed to repeat it to other people."

Honourable history?

Those who want to keep the current secrecy often claim that it was first introduced in the 1930s in order to protect German Jews, who were investing their assets in Swiss banks in order to stop the Nazis seizing them.

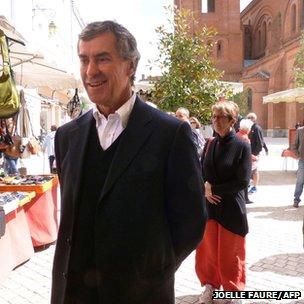

French minister Jerome Cahuzac had to step down after it was revealed he had a secret Swiss bank account

Although this certainly happened, in fact the Swiss Banking Act of 1934 was introduced in the wake of a scandal in which a number of French politicians and businessmen were publicly identified as having hidden their money in Switzerland. The act was designed to protect client privacy in the future.

If the recent events surrounding France's disgraced former budget minister Jerome Cahuzac are anything to go by, some European politicians have continued to benefit from the secrecy.

Mr Cahuzac, charged with sorting out tax evasion in France, was recently revealed to have put hundreds of thousands of euros in a secret Swiss bank account, in the hope of escaping the attentions of the taxman.

Examples like these are causing fury in cash-strapped European capitals. Greece, too, has seen much needed tax revenue disappear into Swiss banks, and a desire to reclaim as much unpaid tax as possible, as soon as possible, is a big reason the pressure on Switzerland is now so great.

Swiss soul searching

Within Switzerland itself, there has been much soul searching over the years, as the Swiss ask themselves whether a policy that seems to work quite well at home, where Swiss citizens pay their taxes themselves rather than at source, is really suitable for foreign clients.

"I think as long as there are places where people can hide their money, it will be really difficult to tackle corruption," says Jean-Paul Mean, who is head of Transparency International Switzerland.

"And," he adds, "Switzerland has certainly profited [from banking secrecy]. A lot of money has come into the country which would not have come without it."

Law professor Philippe Mastronardi agrees. He and a number of other leading Swiss academics have just published a manifesto calling for an end to banking secrecy.

"Is it ethical? No," he says. "For me there is a very important principle, which is the rule of law, and principles of transparency and honesty, which are being violated by the use of the banking system in Switzerland."

'Economic war'

For the Swiss government, the issue has become a political hot potato. Ministers are caught between the reality of needing good relations with Europe and the United States, and a domestic mood that is not inclined to submit to foreign demands.

Yves Nidegger, a member of parliament for the right-wing Swiss People's Party, says the issue is whether Switzerland can set its own laws.

"Are we an independent state where the rules of the parliament apply on our territory or are we a colonial state whose laws are determined by the mighty neighbours?"

Mr Nidegger sees the pressure from Europe and the US as an "economic war", fuelled primarily by jealousy at Switzerland's success in managing so much of the world's private wealth.

He for one is not ready to surrender, and seems prepared to go to quite astonishing lengths to keep Swiss banking secrecy.

"I think Switzerland still has a few cards to play," he says.

"We could for example offer to guarantee the Greek debt, not to pay it, but to guarantee it. We are the only ones able to do that, the Greek debt would be triple A, it would be sellable, and the guarantee would be maintained as long as our banking secrecy is respected."

It is perhaps not an entirely realistic scenario, but it does reflect a widespread resentment over the way in which the EU and the US are seen as dictating Swiss policy.

Negotiated solution?

But while Mr Nidegger seems ready to fight on, many in Switzerland, most notably the bankers themselves, seem ready to settle.

"We cannot be at war with our neighbours on these issues, that is very clear," says Michel DeRobert.

"We see the world, the whole world, moving towards a single standard. If that's the case then obviously we will have to adjust to that standard."

The fact that a leading banker like Mr DeRobert wants to negotiate is the clearest indication yet that Switzerland is now getting ready to accept what was once unthinkable: the end of banking secrecy.

- Published19 May 2013

- Published23 November 2012

- Published5 December 2012

- Published11 April 2012