Could protests be Erdogan's undoing?

- Published

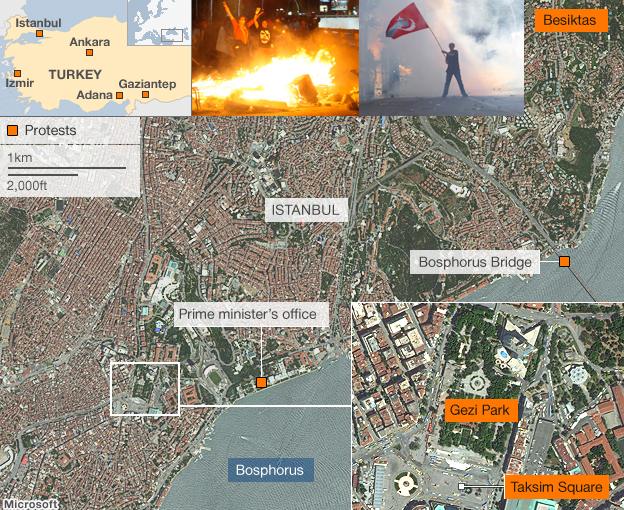

Protesters across Turkey have been rallying for nearly a week now

This week Turkish Prime Minister Recip Tayyip Erdogan decided the crisis at home did not merit cancelling a trip he had planned to North Africa.

He left his deputy to look after damage control in Turkey, and instead presented an unruffled face to the world, surveying guards of honour at airports through his sunglasses, laying wreaths and talking trade and business.

Mr Erdogan has worked hard during his 10 years in office to make the most of one of Turkey's greatest strategic assets - its position between Europe and the Middle East.

When the European Union was at best lukewarm about Turkish membership, it made even more sense to turn towards the Arab world.

Until the Arab uprisings began in 2011, he seemed to be on to a winner. While Brussels struggled with the euro crisis, Turkey projected power, and created jobs at home by doing business in Arab countries.

Big deals were done with Col Gaddafi's Libya. Mr Erdogan cultivated President Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Throughout the region, there was a good chance that the contractors' boards outside major construction projects would display the names of Turkish companies.

Protesters in Turkey and abroad accuse Mr Erdogan of usurping the power

Reaching the limit

But one important rule for an elected leader is never to take your position at home for granted, even if - like Mr Erdogan - you have secured a string of handsome electoral victories.

The first President Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair and others before them became so caught up in foreign policy that they were all eventually undone by what might have seemed the less momentous business of what happens at home.

Mr Erdogan is fond of pointing out that half the Turkish electorate voted for him. He seems to have forgotten, or to have ignored the fact that the other half of the electorate did not.

What has not helped him is that what had been a relatively benign political climate for Turkey before 2011 has changed, for the worse.

Characteristically, Mr Erdogan has not retreated.

He was quick to visit Egypt and Tunisia after they overthrew their leaders. Turkey has tried hard to revive the contracts it had with Libya.

Despite its traditionally secular ideology, Turkey was suggested as a model for a Muslim democracy. Some Arabs, who took to the streets against their own leaders, are having second thoughts about that as they watch pictures of Turkish riot police attacking demonstrators.

When the war in Syria started, Prime Minister Erdogan's Turkey became a leading supporter of the Syrian armed rebels, simmering close to a state of undeclared war with the Assad regime.

Mr Erdogan seemed unconcerned that he was alarming and alienating important sections of his own population by getting so involved in the Syrian war.

That is one of the factors, though far from the only one, influencing the protests on Turkey's streets. It feeds into the perception that the prime minister believes he knows what is best for Turkey, and will not tolerate dissent.

Mr Erdogan needs to attend to affairs at home. He has reached the limits of what is possible without the consent of those who did not vote for him.

He is still Turkey's most popular politician. But if the country continues to polarise, that might end up counting for less.