ERT closure: Silencing of broadcaster shocks Greece

- Published

Olga Psaridou has lost her job after 15 years at ERT

It took less than five minutes for both Panagiotis Kostas and his wife, Olga Psaridou, to lose their jobs. That was the length of Tuesday's announcement by a government spokesperson that Greece's state broadcaster, ERT, would be shut down at midnight.

The couple, who have one child, are both ERT journalists.

Ms Psaridou, 42, is a news anchor and Mr Kostas, 49, the editor-in-chief of the news programme at ERT's third channel, ET3.

"We are in a state of shock. And we are mad with anger that this could be the way it all ends. I have been working for 17 years for ERT and my wife for 15," Mr Kostas says.

The couple are among the approximately 2,700 employees who have been laid off by ERT.

The decision, which is intended to placate Greece's international lenders and demonstrate the decisiveness of the government to move ahead with reforms, shocked not only ERT employees, but the entire nation.

As Giorgos Toulas, a veteran radio producer at ERT, wrote in an article for the magazine Parallaxi: "This morning, the alarm clock woke me up as it has always done for 25 years. I went to work, but ERT was no longer there. The building was locked, the internet access suspended, telephones dead.

"ERT's radio had been on the air since 1938. It was not silenced during the German occupation or the military junta. But it was last night".

'Easy target'

The leading party in the governing coalition, the conservative New Democracy (ND), insists that ERT was a rotten apple, suffering from chronic mismanagement, lack of transparency and waste.

According to government sources, among the many sins of ERT was that not a single employee had been hired transparently or on merit.

Julie Peacock reports

A completely new ERT, expected to be up and running by the end of summer, is supposed to operate with a third of the staff and half the operating cost. The government promises to model it on the BBC, Italy's RAI and the Germany's ZDF.

Even ERT employees concur that the broadcaster had a questionable past, being used for political appointments and offering exorbitant pay to a few handpicked reporters, executives and advisers.

Mr Kostas, however, says that these were the exception.

"My [monthly] net salary as an editor-in-chief with one child and 17 years of service is 1,440 euros [£1,220; $1,910]. My wife's is 1,350 euros. We are just an easy target," he adds.

'No other option'

Not everyone is unhappy with how things turned out.

Pashos Mandravelis, a prominent columnist for the conservative newspaper Kathimerini and a vocal critic of ERT, says the government made the right decision.

"There was no other option. Every time any restructuring was attempted, ERT unions rebelled. They made the untenable demand of not a single lay-off."

"In a country devastated by the crisis and suffering from such unemployment rates, this was impossible," he explains.

A poster inside an ERT TV gallery reads: "The revolution will not be televised"

ERT's critics recall the failed attempt by the former government of the socialist Pasok party to restructure the broadcaster.

The plan floundered because of hostility from unions. Now, it is the basis of the new bill restructuring the broadcaster, tabled by New Democracy.

Mr Mandravelis says it is paramount that the new state broadcaster is well-run, transparent and independent.

ERT reporters also admit that streamlining the broadcaster was a necessity.

One point that both ERT's critics and supporters agree on is that the same government that has pledged to rebuild the broadcaster contributed to its problems.

"ERT has become worse in the past year. Both in terms of dependence on the government and of staffing choices", says Mr Mandravelis.

Mr Kostas says it was the government that gave a TV programme to the daughter of a former ND minister "with a salary of 3,500 euros a month".

'Bipartisan committee'

Elias Mossialos, a professor of health policy at the London School of Economics, was the minister of state who in 2011 presented the Pasok-led government's plan to reorganise Greece's public service broadcasters.

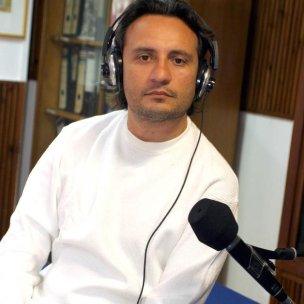

Giorgos Toulas says ERT was not even silenced in WWII

He also says the current government had already "had one year to reform ERT and did nothing".

"ERT should be made fully independent, its staff evaluated by a third-party organisation, and the restructuring must be supervised by a bipartisan committee - not by the same minister who appointed a constituent of his to ERT or gave a TV programme to an ND politician's daughter."

However, the deputy minister who oversaw ERT and announced its closure, Simos Kedikoglou, insists his "hands were tied".

"The culture of unionism meant that ERT even ignored my direct orders to refer employees facing serious charges to disciplinary boards," he says.

He also dismisses claims of ND nepotism and any responsibility for the broadcaster's appointments.

"This is how ERT used to work," he says. "This will not be the case with the new ERT. And besides, it was only a handful of people, whom I did not personally appoint. ERT had its own management and the country is ruled by a three-party coalition."

'Last bastion'

Developments at ERT bode ill for Greece's journalists in general - perhaps the only professionals who are even less popular than its politicians.

Thousands protested outside ERT's headquarters in the capital, Athens

"Employment in the public sector was the last bastion for journalists. The [private sector] has collapsed as advertising revenue has plummeted," says Makis Voitsidis, the head of the Journalists' Union in northern Greece.

According to union leaders, unemployment among journalists currently stands at 50%. Most Greek media companies face tremendous financial challenges and have implemented massive job and salary cuts.

Under these conditions, Mr Kostas fears the worst.

"We are being kicked out on the street, at a time when the job market for journalists is simply dead."

- Published12 June 2013

- Published12 June 2013

- Published28 April 2013

- Published27 November 2012