Kindertransport: Children who fled the Nazis to Britain

- Published

It is 75 years since Britain sanctioned a mission to bring Jewish children to the UK after the devastation of Kristallnacht, when the Nazis organised anti-Semitic attacks in Germany and Austria, including smashing windows of Jewish-owned businesses.

Ten thousand children were evacuated by parents desperate to get them to safety. Acts of commemoration are taking place this week, but as survivors grow old, how should their stories be remembered? BBC Newsnight hears the stories of four of them.

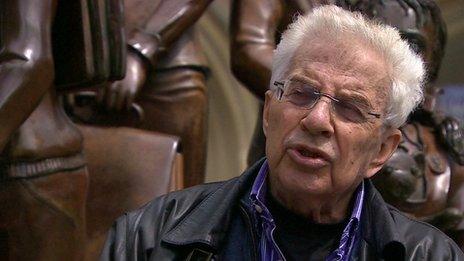

FRANK MEISLER, TRANSPORTED FROM DANZIG, AGED 12

I slept through the actual night of Kristallnacht and in the morning as I walked onto the streets there was glass everywhere, and crowds, and I realised something very sensational had happened.

There were Nazis standing around in uniform and big smears all over the walls saying "Die, Jews" and so forth. And through all of this I walked to the school.

It was from Kristallnacht on that the Kindertransport started.

I don't remember my parents discussing the decision to send me, although they must have. My father was abroad at that time because Jews had been made to leave their businesses, and my father had transferred his truck business from Danzig [now Gdansk] across the border into Poland.

My mother had two sisters and her mother living in London at that time, so it was arranged that I would be taken in by my mother's family.

'Totally disorientated and hungry'

My group was the last of three that left Danzig. I was one of 18 children, and we travelled for three days, passing through Berlin, at Friedrichstrasse station, with a Gestapo guy who accompanied us, and a member of the Jewish community who took us all the way to London.

In Berlin we had arrived at around four or five in the morning, and an aunt of mine was standing in the station with bananas for all the children because she had heard that we were passing through.

The Gestapo guy got off at the railway station at the border between Holland and Germany, and we then went on to the Hook of Holland, and from there by ferry to Harwich and from Harwich to Liverpool Street station in London.

By the time we arrived in Liverpool Street we had been sleepless for three days and three nights and we arrived totally disorientated. We were hungry and didn't know the language, and it was a strange world to us.

There was a mixture of emotions, a combination of excitement at being in a strange place and of sadness at having parted with one's parents. We weren't aware, and I think maybe many parents weren't quite aware, that this was the last parting ever, because of course the [concentration] camps had not been built.

That's what I wanted to show in the sculpture that I did for Liverpool Street station - disorientated, tired, slightly elated, somewhat depressed, bewildered children coming into a wartime England not knowing a word of the language, I wanted to show it the way I remember it was.

My mother's two sisters were at Liverpool Street station and off I went. Others were taken in by people who had previously agreed to accept children to their homes. Where there was no place for the children in homes, they were taken to some kind of hostel.

One of my aunts was married to a Bavarian doctor who had resettled a year or two before and had a practice in Harley Street. They lived with my grandmother, so there was my mother's sister, her husband, their son and my grandmother.

When my parents said goodbye to me on the platform, my father said: "Whatever happens, study, go to university," which I tried to do and did. That's the advice I got, and for better or worse I carried it out.

'I'm an orphan'

I had to learn English first, for which I got private lessons, and then was accepted into a boarding school in north London.

In terms of what was happening back home during the war, I think the British government suppressed a great deal of what they knew concerning the concentration camps. They had their own reasons to underplay this, but the German refugees here knew all about it.

The rumours were rife there, and people knew what was happening in Auschwitz and in Buchenwald, that something terrible was happening there, which the British authorities did not want known.

I remember being taken by the school to a play in the West End, and it was in the middle of the play that I was sitting there with all the other students, when I suddenly said to myself: "I'm an orphan."

I suddenly realised that the chances of my parents still being alive after what I had heard were minimal. I don't know why it came to me in the theatre, but I remember sitting there in that chair and coming to that understanding.

I got the confirmation of this from the Red Cross after the war, and also from my father's brother, who had survived and had himself passed through Poland during the war and looked for them.

When I try to piece together what there would be in common between all of us who were on the Kindertransport, it would be that, as I wrote in a book, we entered the train in Danzig as children; we disembarked in Liverpool Street Station as adults, because we were now responsible for our own lives.

We experienced too much too soon. I think that probably is the epitaph of our youth.

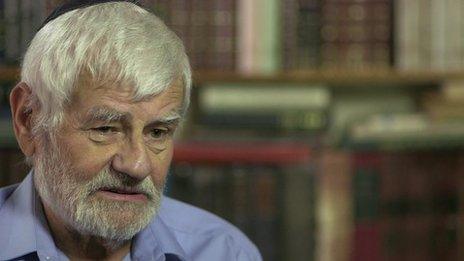

BERND KOSCHLAND, TRANSPORTED FROM BAVARIA, AGED 8

There are a number of things that often play in the back of my mind as I think about the transports, the feeling that parents must have had to make that decision to send their child away; added to that, the promise of "we'll see you again shortly, hopefully", which of course in many cases never occurred.

I was a young child and I cannot remember my reaction to being told I was going abroad. I know my parents made me a promise. They promised me a suit with long trousers, because in those days boys wore shorts only, when I had my bar mitzvah.

But of course the promise was unfulfilled as they didn't survive.

I cannot remember much of how I felt at my time of leaving for England. It's almost like a curtain came down and blacked it all out.

I didn't know the language except one sentence. Interestingly my parents taught me a sentence in English, which was: "I'm hungry, may I have a piece of bread?", or words to that effect, which I've fortunately never had to use.

Prayer books and a photo album

All of the children were allowed only one small piece of luggage. I still don't know to this day why, but I was able to take two cases with me: an ordinary big case and an old-fashioned trunk.

I had clothes and a hairbrush, which mother packed to make sure that her darling little son kept his hair tidy, and a shoe bag and other bits.

Father would have probably left most of the packing to mother, but he ensured that I took things that were important from a Jewish point of view. He came from an Orthodox Jewish home and he made sure that I had prayer books. And there was a photo album that was given to me, a little tiny one.

I don't really remember saying goodbye to my father and sister. My mother came with me to Hamburg and we boarded the liner and I said goodbye to her there.

When I got to England I was sent to Margate, where I lived in a group of 50 youngsters up to the age of about 16 or 17. I was the youngest. I learned English and learned to play games which I'd never heard of, such as hopscotch.

I was lazy when it came to writing to my parents, and also I had to choose whether I would use my pocket money to buy sweets or stamps, but I did write and I got letters back.

Unfortunately I destroyed all those letters when war broke out. An older child said: "You can't keep those, if the Germans come here it's no good," so sadly I destroyed all my parents' letters.

Once the war broke out there was no further communication. Around about 1942-43 we tried to contact them via the Red Cross, as a number of people did, but we heard nothing, as by that time they were no longer alive.

My father died in January 1942 and my mother in the March. I heard about my parents' death in 1945. My sister met me from school and told me and I just went on with my life. There was nothing much more I could do and that was that.

I'd already sort of lived with the loss in my own mind because I'd not heard from them since the war began.

GERTUDE FLAVELLE, TRANSPORTED FROM VIENNA, AGED 11

I remember it was night when we went to the railway station because, I think, they didn't want the population to know what they were doing.

In a way I didn't understand it all. I wasn't stupid or anything, but it was just a thing that you couldn't comprehend. I remember my father telling me that I would like it in England because I would be able to ride the horses, but the reality wasn't like that at all.

The journey was such a blur. On the boat we had bunks because we crossed in the night. I remember going to the toilet, and when I was out of the compartment I cried and one of the helpers who was on the journey said: "Don't do that, you'll set the young ones off."

When we arrived in England we stayed overnight in London with the uncle of Eve, the friend I had travelled with. In the morning we took a train to Hinckley in Leicestershire, where we were both due to go.

I remember my foster parents coming in. He wore a bowler hat, which he took off. He was quite an elderly gentleman and she was a fairly stern-looking lady.

'I was basically a maid'

I don't know whether they were just the type of people who didn't hug or kiss or anything. I can't ever remember being hugged, you know? Of course we couldn't talk together either, which I suppose was a hindrance.

I went to school for a couple of years, and my foster parents went to work, both of them.

I was basically a maid, hoovering and polishing and washing up, and I was a young pair of legs for going shopping.

Then of course we come to the time when I left school at 14. On the very next Monday I was introduced to my first factory job, where I promptly ran the needle of the sewing machine through my thumb. I don't think I lasted very long in that factory.

But then there was always another one. And so it went until I was 18, when I decided to leave my foster parents. I took lodgings with one of my workmates.

Until I left my foster parents, I was sort of continuously homesick, and it's a horrible feeling. You know, it was always there.

We didn't part on terribly good terms, because I think they thought I would live there for ever. I suppose they were fond of me. I just don't know.

It was a matter of luck who you went to and I just wasn't that lucky. But then again you've got to think that they saved my life.

EVE WILLMANN, TRANSPORTED FROM VIENNA, AGED 5

I came to England in April 1939 and I was five and a bit years old. The passport I travelled on was issued by the German Reich, and on the front page there was a J in red to designate that I'm Jewish.

My father was a doctor and he had his practice near the showbiz part of Vienna. My mother worked as a dancer in one of the theatres and she went to him as a patient and they fell in love. Since she wasn't Jewish, she converted.

I don't remember getting on the train, but I do remember the train stopping and people coming in and giving us a sweet drink and then we carried on.

First I stayed with quite a strict family. I recall silly things, like having to wear a straw bonnet and being forced to make my own bed with hospital corners. I don't think I stayed there that long. It probably wasn't more than a year or so, and then I moved to Cambridge.

'A lovely holiday'

I remember at one point a card coming from my parents, and rushing down the stairs and then being quite emotional. I think that must have been the first contact then, since I remember it as an event.

In Cambridge I moved to a very nice family. They had a son about the same age as I was, a beautiful house and a big dog, and I started school. I think the family would ideally have adopted me because they had a boy and I was a girl, but then the mother had to go into hospital to have an operation and so I went to another family in Cambridge.

After that I was in a hostel and another family, until eventually I moved to stay with my uncle from Moravia and his family, who had settled in Hartlepool.

The refugee committee hadn't wanted me to go to them until they had a stable set-up, but when they became established in West Hartlepool and my uncle got a steady job as a teacher I was allowed to have a holiday with them there to see how I liked it.

I had a lovely holiday and my aunt said to me: "You know you're going back now, but when you come back it will be for ever," and so it was.

My mother was working in a factory during the war and she was killed when it was bombed. I felt sad, but I didn't really know her. I just sort of had flashes of memory of her.

My father managed to survive the war and in 1948 he came over, full of hope, to see his only child, but it was quite a traumatic experience because I'd more or less got a new father. Things did thaw during his stay but it was quite hard because for him it was a continuation, but for me it was something new.

I was all geared up to go to Vienna the following year, but unfortunately in the February of that year he had a massive heart attack and died.

WATCH NEWSNIGHT'S FULL FILM ON THE KINDERTRANSPORT

Newsnight meets four of the thousands of Jewish children sent to the UK from Germany and Austria 75 years ago, in the wake of the devastation of Kristallnacht.