Alexei Navalny convicted: The fates of Putin's enemies

- Published

Russian opposition leader and blogger Alexei Navalny (C, front) and his wife Yulia (R, front)

Russian anti-corruption blogger and opposition politician Alexei Navalny has been jailed for five years for fraud, after a trial he says was politically motivated.

Mr Navalny could now be barred from running in the Moscow mayoral election set for September. He also joins a growing list of opponents of President Vladimir Putin who have ended up on the wrong side of the law or in exile, or have met their deaths in suspicious circumstances.

Oligarchs

When Mr Putin first became president in 2000, he immediately set about curbing the power of the oligarchs - the group of billionaires who exerted huge influence over Russia's political system and media.

His first victim was media magnate, Vladimir Gusinsky, the owner of NTV, a station that at the time was highly critical of Moscow's war in the breakaway republic of Chechnya and was home to the satirical puppet show Kukly, which mercilessly mocked the new president.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky could face further charges

When Mr Gusinsky refused to allow the Kremlin to influence NTV's editorial policy he quickly found himself charged with fraud in June 2000, and fled the country shortly afterwards.

Within months, he was joined by his fellow media magnate and political fixer Boris Berezovsky.

Mr Berezovsky is believed to have played a key role in helping Mr Putin into power in 2000. But he quickly fell out of favour with the new regime and sought refuge in the UK.

Mr Berezovsky continued to plot against Mr Putin and to be held up as a bogeyman by the Russian media until he was found dead in the bathroom of his Berkshire home in March this year. Police have said that there is no evidence of anybody else being involved in his death.

Perhaps most famously Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the former head of the now defunct oil company, Yukos, was targeted when (like Mr Navalny) he accused Mr Putin and his associates of conniving in massive corruption.

He has subsequently been convicted in two trials of tax evasion and fraud. Following his second trial in 2010, Amnesty International recognised Mr Khodorkovsky and his co-defendant, Platon Lebedev, as "prisoners of conscience".

Mr Khodorkovsky is due for release in 2014, but there are signs that he could face further charges.

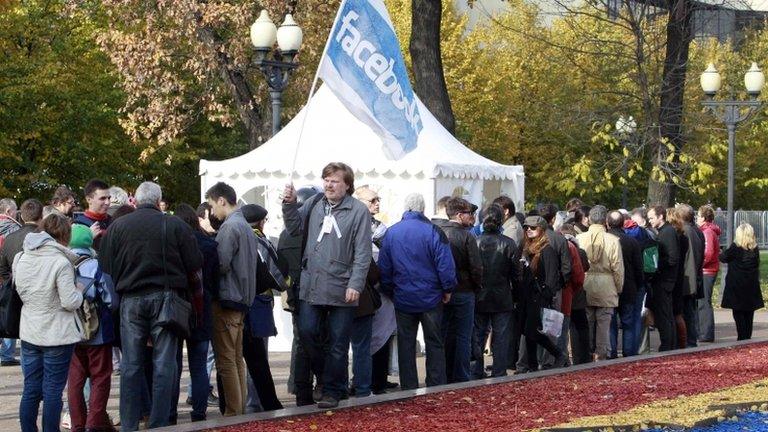

Politicians and protesters

Pussy Riot protested against President Putin's running of Russia's oil industry

Political opposition to Mr Putin is becoming an increasingly risky business, with numerous activists facing charges or in jail.

Two members of feminist band Pussy Riot are serving two-year prison sentences for "hooliganism motivated by religious hatred" after performing an "anti-Putin punk prayer" in Moscow's main Orthodox cathedral in February 2012. A third member of the band had her sentence suspended on appeal.

Meanwhile, criminal charges of affray, incitement to violence and assaulting police officers are pending against more than 20 activists involved in disturbances at a demonstration in Moscow on the eve of Mr Putin's inauguration as president for a third term in May 2012.

Sergei Udaltsov, a left-wing leader of the protest movement, is under house arrest after being charged with incitement to mass disorder on the basis of video evidence shown on Russian TV. If found guilty, Mr Udaltsov (like Mr Navalny) could face a substantial prison sentence.

Some members of the Russian opposition, such as former Deputy Prime Minister Boris Nemtsov, continue to defy Mr Putin despite regular harassment and detention for public order offences.

Sergei Udaltsov appeared in court in May 2013

Like Mr Navalny, Mr Nemtsov is a member of the opposition's alternative parliament, the Coordination Council. He is also co-author of a report accusing Mr Putin of leading Russia to ruin.

Another member of the Coordination Council, former world chess champion Garry Kasparov, has joined the growing list of Russia's political emigres.

But, as the fate of former FSB (Federal Security Service) officer Alexander Litvinenko showed, even exile carries risks for Mr Putin's opponents.

Mr Litvinenko died in London in 2006 after being poisoned by radioactive polonium.

Media

It is not just oligarchs and politicians who have to fear Putin's disfavour. Journalists and TV presenters, too, have to be wary of offending the Kremlin.

Ksenia Sobchak, whose father Anatoly was Mr Putin's political mentor, was a familiar face on light entertainment shows on Russia TV until she joined the protest movement following the disputed parliamentary election in 2011.

Ksenia Sobchak

Since then, her lucrative contracts on mainstream TV have dried up and her appearances have been confined to the niche liberal channel Dozhd - a refuge for several dissident journalists.

Mr Putin makes little secret of his hostility to journalists who challenge his authority.

Shortly after the murder in 2006 of Anna Politkovskaya, a reporter with opposition newspaper Novaya Gazeta and fierce critic of the Kremlin's policies in Chechnya, Mr Putin dismissed her political influence as "negligible".

Ms Politkovskaya is one of five Novaya Gazeta journalists who have been murdered or died in suspicious circumstances since 2000.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. For more reports from BBC Monitoring, click here. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter , externaland Facebook, external.

- Published18 July 2013

- Published10 July 2013

- Published23 October 2012

- Published25 March 2024