The EU's curious silence over Spain's Rajoy

- Published

- comments

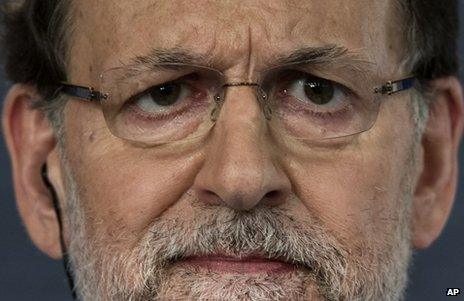

Mr Rajoy was challenged by a reporter on Monday

Spain is the fourth-largest country in the eurozone. Although there are some more optimistic signs - like an increase in exports - the country remains in recession.

In the past year the economy has shrunk by 1.8%. Unemployment is close to 28%. Debt is still rising. The IMF has warned that although Spain's banks are stronger than a year ago they still face high risks. The banks' bad loans are still rising. In other words, although there are slender signs of a recovery, Spain remains close to the casualty ward.

Europe's leaders, including Angela Merkel, have placed a lot of faith in Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy. He has a strong majority in parliament and is regarded as a safe pair of hands. The word of his government, when it commits to reforms, is respected.

But Mr Rajoy is facing serious allegations of corruption. The former treasurer of his party alleges that they ran a slush fund fed by illegal donations from construction companies. Some of that money, he says, was passed to Mr Rajoy and other party leaders. He has testified that 25,000 euros (£21,500; $33,000) was handed to Mr Rajoy as recently as 2010.

The treasurer, Luis Barcenas, has changed his story. He was detained last month while under investigation for running the slush fund and for holding secret Swiss bank accounts. Yet he has provided a detailed record of these transactions which have been published.

More than six out of ten Spaniards now believe Mr Rajoy accepted some of these undeclared cash payments, a recent opinion poll suggests. More than 80% believe his Popular Party was involved in illegal financing, according to the same survey.

The opposition leader is Alfredo Perez Rubalcaba. Although he stands to gain from Mr Rajoy's discomfort he makes the point that "until he answers these questions, Rajoy cannot govern". He has demanded that he go before parliament before the summer recess to explain himself.

Mr Rajoy has dismissed the allegations and seems irritated that questions are being asked. He has repeatedly said he will not stand down. To date he has seen no need to provide a detailed explanation.

'Bad communicator'

In most democracies that would not wash. He would have faced forensic questioning and his job would have been on the line. Earlier this week, during a visit by the Romanian prime minister, it was a Romanian journalist who asked Mr Rajoy about the corruption scandal.

Tom Burridge reports on Spaind "most angry" demonstration since reports of the scandal broke

"Well I normally respond in parliament," replied Mr Rajoy. "I answer questions, I take part in debates and I always answer to journalists when I'm asked about it."

That is a rather generous interpretation of what has happened. The prime minister has not faced a forensic cross-examination. The Spanish people need to know whether over a 20-year period he received any extra money from a party fund that was not declared. It would be interesting to know whether he would agree to an independent judicial enquiry to establish the truth of these allegations.

So after much prompting, Mr Rajoy will appear in parliament next week on 1 August, when most Spaniards are on vacation. The question is whether he will continue with a broad dismissal of the allegations or whether he will be able to lay this scandal to rest with a point-by-point rebuttal.

Mr Rajoy's reticence is in character. The view in Brussels is that he is a bad communicator. When the Spanish banks were bailed out he did not appear before the cameras until the following day.

Unusual silence

European officials, however, give him high marks for committing to far-reaching reforms. But Europe's leaders and officials have also been unusually tight-mouthed over this corruption scandal - considering the importance of Spain to the eurozone.

On Tuesday, EU Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding waded into Bulgarian politics by saying "my sympathy is with the Bulgarian citizens who are protesting against corruption".

Also the leaders of the various political groups in the European Parliament are never shy in commenting on prime ministers who they suspect of flouting European values. Hungary is a case in point.

On several occasions, Europe's leaders have chastised the Greek government and, in no uncertain terms, have told the Greeks what they should do. But on Spain there is a curious silence.

It may be that Mr Rajoy is entirely innocent but, at a critical moment for his economy and for the eurozone, many of his own people do not believe him.