Germany's new anti-euro AfD party causes political stir

- Published

Nobody doubts the intellectual clout of Germany's newest political party. Alternative fuer Deutschland has enough heavyweight economists to keep a decent-sized university going.

If doctorates meant votes, it would be home and dry in the elections. After all, it's been called a "party of professors".

Its difficulty is that the label is usually meant as an insult. Its detractors portray it as a party of naïve academics who have waded into the rough seas of politics only to sink without trace at the federal election in September.

And it is true that sometimes its press conferences seem disorganised. Speakers turn up late or go to the wrong venue.

But, on the other hand, the AfD (as it calls itself) is starting to make waves. Not tidal waves big enough to sweep Chancellor Angela Merkel from power, but a swell of opinion large enough to make the established parties feel uncomfortable.

'Bourgeois protest party'

Its openly anti-euro message has prompted a debate in the governing Christian Democrat (CDU) party, for example - is silence the best policy or should the party's pro-Deutschmark message be addressed head-on?

And the main opposition party, the Social Democrat SPD, is turning increasingly to the euro as a potent stick with which to beat Chancellor Merkel. "Germany will have to pay for the stability of Europe and the eurozone," as the SPD chancellor candidate Peer Steinbrueck put it over the weekend.

The AfD usually gets 2-3% support in the opinion polls. If it can raise that to 5%, under the electoral laws of Germany it gets seats in the Bundestag (lower house), and in a coalition system, small parties then have power.

The issue of the euro is back on the political agenda in Germany after Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble said that Greece might need another bailout. And a recent poll of Germans conducted by the University of Hohenheim put the euro crisis at the top of people's concerns, ahead of wages and unemployment.

So the AfD leadership says that the polls understate support - their theory is that many people do not admit that they might vote for them, because the party is outside the mainstream.

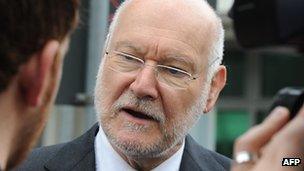

Economist Joachim Starbatty, one of the AfD's senior members, wants Germany to quit the euro

It is certainly getting respectable crowds at public meetings. Last weekend, hundreds turned up to listen to AfD speakers at the Saengerhalle, a social club in Stuttgart.

Alternative has been called a "bourgeois party of protest", and you could see this "buergerlich" aspect in the audience - solid German citizens, enjoying beer and sausage as they listened to speeches.

The main speaker was Joachim Starbatty (or, to give him his full academic title: Prof Dr Joachim Starbatty, an economist at the University of Tuebingen).

With a neat beard, scant grey hair and glasses, he looked every inch what a studious academic is meant to look like. He did not look like a rabble-rouser, yet on stage he was transformed into a passionate and effective speaker.

He made the case against Germany staying in the euro. If his party gets into the Bundestag, he said, "we will have a platform to articulate our ideas, because now the old parties are silent concerning the problems of Europe. But we can say the truth to the people".

Far-left 'attacks'

On the streets, the leadership says campaigners are generally met with polite curiosity and genuine interest, but occasionally with outright hostility and even violence from the far left. Their founder, Professor Dr Bernd Lucke, an economist from the University of Hamburg, was attacked on stage.

The Stuttgart candidate, Prof Dr Lothar Maier, of the University of Stuttgart, told the BBC: "Most reactions are positive or, at least, they are asking serious questions. People start to realise that AfD is becoming a serious alternative."

Prof Maier did not accept that the party was a party of professors. "They call us a party of professors but if you look at the structure of our membership, this is not so. Maybe, it's 2% or 3% who are professors at the most," he said.

"We have 20,000 members in Germany and there aren't so many professors in Germany. Our membership is coming from all strata of the population.

"Maybe we should argue in a more aggressive way but we avoid it to maintain our serious image. We don't want to appear as a rough-type party, because we are doing serious politics. We don't want to mobilise the street. We don't want violence, though we are sometimes the victims of violence."

The AfD says its political agenda appeals to members from the left and the right

Apart from the attack on the party's leader, Prof Maier said posters were routinely torn down: "We put up 1,000 posters in Stuttgart and within 24 hours, 80% were destroyed. So there is some political force organising violence against us.

"The most probable explanation is from the extreme left. Our people have been attacked in Goettingen."

The far left sees AfD as an anti-immigration party. The AfD denies this, saying it is in favour of a system of immigration control, which allows people in on the basis of needed skills.

The party, though, does not seem like other anti-immigration parties in Europe, where there often seems to be an undercurrent of racism, and in which immigration is the big issue. For the AfD, the euro is the big issue.

Whatever the views on the benefits or not of the euro, it is now on the political agenda in the forthcoming elections. Chancellor Merkel may have decided that it was best left alone - let sleeping dogs lie, as it were - but the euro dog is now barking.

Nora Hesse of the Open Europe think-tank in Berlin argues that it is now best addressed.

"Maybe politicians are avoiding the topic because it is dangerous for them as they try to be re-elected," she said. "But, at the same time, politicians have to realise that they are running the risk of people - citizens - not feeling they are represented by the politicians that they vote for."

The likelihood remains that AfD will not get the requisite 5% it needs to get a seat in parliament. But that is not certain. The debate is fluid. Don't write off the Alternative yet.

- Published14 April 2013

- Published23 August 2013

- Published4 September 2023