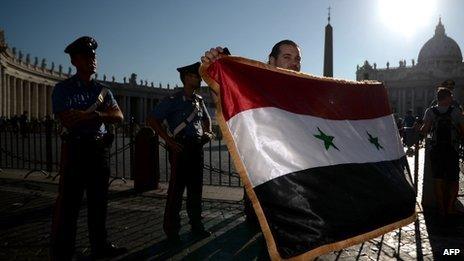

Syria crisis a 'defining moment' for the European Union

- Published

- comments

The response to the Syrian crisis is critical both for the EU and for the US

In the coming days - or perhaps weeks - much will be learnt about the United States and Europe.

In America, with Congress returning this week, the open and underlying question is whether the United States wants to continue as the world's policeman.

The immediate issue is about how to respond to the use of chemical weapons in Syria but what is being debated in town hall meetings across America is whether, after wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the country is inclined to step back from bearing the heavy burden of intervention on the world stage and to become more isolationist.

The days ahead will also define the presidency of Barack Obama and determine what authority he will retain in his final years in the Oval office.

The crisis is also a defining moment for Europe.

It raises again the question of whether the continent can marshal an effective voice when it comes to decisions of war and peace.

After the chemical attack of 21 August it was Europe's two main military powers - the UK and France - which led the way in demanding that the Syrian regime needed to be punished and deterred.

As regards the EU - as an institution - it took almost 15 days to set out its position. The Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta, talking to the BBC, said that European decision-making was "too complex, too long".

The EU has "a lot of problems when there are sudden decisions to make".

Inward-looking argument

At the G20 in St Petersburg four EU countries - Britain, France, Italy and Spain - signed a statement calling for a "strong response" to events in Syria.

There were no indications of what 'a clear and strong' EU response to the Syrian crisis would entail

That did not play well with Angela Merkel and Germany did not sign.

She wanted to wait until the following day when EU foreign ministers were meeting in Vilnius.

"I don't believe," she said, "that it is right for four countries to agree to a united stance without the other 23 that cannot be there, knowing that 24 hours later all 28 will be gathering around the table."

One diplomat pointed out that this inward-looking argument was more about the EU than Syria.

The EU statement, when it came, said "a war crime and a crime against humanity" had been committed.

It said "there was strong evidence" that the Syrian regime was responsible.

It went on to declare that a "clear and strong response is critical to make clear that such crimes are unacceptable and there can be no impunity".

US Secretary of State John Kerry welcomed the statement, particularly the use of the word "strong", but there was no European backing for military action.

Faith in the UN

Indeed much was left unsaid. There were no indications of what "a clear and strong response" should entail.

The French president is under pressure not just from his own public opinion but from his European partners

EU foreign ministers insisted that "the international community cannot remain idle" but set out no course of action.

As an institution, the EU's instinct is to place its faith in the UN.

It wants to see a peace conference in Geneva.

There are, however, no indications that either President Assad, whose forces have made progress recently, or the disparate rebels see much advantage in talking in Switzerland.

Only their sponsors - Russia, Iran and Saudi Arabia - can push them towards a peace conference, and the conditions do not appear to exist for that at the moment.

Sanctions, as shown in the case of Iran and its nuclear programme, are rarely effective.

The problem with the UN is that this crisis has exposed its flaws and limitations. There is a stalemate.

Some leaders at St Petersburg were privately pointing out that many countries are taking cover behind the formula that they would only back military action with the backing of the UN, secure in the knowledge that Russia and China will block it.

So in Vilnius, President Hollande of France was praised for stating he would not engage in military action until the UN inspectors had delivered their report - probably later this week.

They are likely to identify which chemicals were used and which gas was delivered but they will not apportion blame.

The French president is under pressure not just from his own public opinion but from his European partners to try again to seek a UN mandate for military action.

Such a resolution is likely to run up against a Russian veto.

One US official said in reference to the UN: "We have been clear there is not a path forward there."

They question whether, as time passes, President Hollande will be willing to be America's sole European ally in supporting a military strike.

So crises define countries and international institutions.

The EU has proved effective in delivering humanitarian aid and, occasionally, in acting as a diplomatic broker.

What is less clear is whether it has the will or the ability to act decisively in the face of an international crisis.