Why chemical weapons provoke outrage

- Published

Even coming amid Syria's bloody conflict, the 21 August attack shocked many

It has been just over three weeks since the world woke up in horror to what appears to have been a mass chemical attack on residential areas in the suburbs of Damascus on 21 August.

Yet some are asking why, in a conflict that has already killed at least an estimated 100,000 people, many in the most barbaric way, should the use of chemical weapons be any more abhorrent?

After all, long before that dreadful early Wednesday morning in August, Syria's ever-growing list of atrocities already included reports of the indiscriminate shelling of residential areas, suicide bombings, beheadings, fatal torture, even napalm dropped on a school playground. So why the crescendo over chemical weapons?

Legacy of WWI

"Chemical weapons are unacceptable," says Thomas Nash, an arms monitor with Article 36, a UK-based body "working to prevent unacceptable harm caused by certain weapons".

"But it's equally unacceptable, I would say, to be shelling areas with explosive weapons where people are living.

The experience of poison gas use in WWI helped form the taboo on their use

"I think we should remember that all of these rules and regulations about which weapons are allowed are a means to an end. They are a means to alleviating and preventing humanitarian suffering that we've been seeing. And it applies to cluster munitions, incendiary weapons, explosive weapons in populated areas, as well as chemical weapons," Mr Nash adds.

But chemical weapons hold a special horror, partly because poison gas is often invisible, partly because of the indiscriminate way it can seek out every hiding place, and partly because of the agonising death it can cause.

The horrors of gas attacks in the trenches of World War I were supposed to teach the world: "Never again".

Yet before chemical weapons were outlawed by the Geneva Protocol of 1925, the British government approved the use of poison gas against rebel tribesmen in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Historians say mustard gas was used at that time in northern Iraq.

Winston Churchill was said to be an advocate and it was feared Hitler would use them against Britain. In the end, this country was spared but others were not.

The gas Zyklon B was used on a massive scale by the Nazis against Jews and other victims in extermination camps.

Kamran Haider: "It was a miracle I survived"

Japan used poison gas against the Chinese in the 1930s and is still paying for the clean-up, Mussolini used it in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) during WWII and the Egyptian air force used it in Yemen in 1967.

The US also drenched vast areas of south-east Asian jungle with the chemical defoliant Agent Orange, which reportedly killed thousands, during the Vietnam War.

Miracle escape

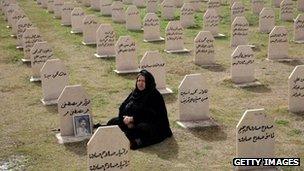

No single chemical attack in recent years compares to the horror of Halabja. In March 1988, Iraq's President Saddam Hussein ordered a Kurdish town in northern Iraq to be drenched with mustard gas and nerve gas, killing over 5,000 people almost immediately.

The Kurdish town of Halabja became a byword for the brutality of Saddam Hussein's regime

Kamaran Haider was 11 at the time. When the bombardment began, he, his family and others rushed to their shelter.

Mr Haider told me that at first it was conventional bombs that fell. Then they smelt a strange odour of fruit and garlic and they knew at once what had happened.

"When we felt that smell, especially my mum and dad when they smelt it, we knew that's a chemical weapon.

"Then they started shouting and crying. It was very horrible because chemical weapon is very different from other bombs. Other bombs you can hide yourself in a shelter or mountain or somewhere but chemical is mixing with the air, you cannot hide.

"So when my mum knew that it was chemical weapon she ran up to the kitchen which was upstairs and she brought some towels... with a bucket of water. And she said: 'Put it on your face... to prevent from burning', because chemical burns the skin or makes you go blind."

Mr Haider's mother rushed outside with his brother to try to find a boy who had run outside.

They found him lying already dead and seconds after she came back into the shelter she too succumbed to the effects of the poison gas. That day Haider lost his father, mother, only sister, both brothers and a cousin.

"It's a miracle I survived," he said, "because of the 35 people in that shelter only me and my friend Hoshyar survived.

"Because I stayed in the shelter among the bodies for 3 days without water, food, electricity, nothing in the shelter and I was severely poisoned by chemical weapons, I was completely blind, my skin burned, and I felt many times sick and lost consciousness," Mr Haider says.

So it's the prospect of another Halabja - or indeed another attack like the one in those Damascus suburbs - that is spurring so much of the international community to prevent it recurring.

Col Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, a former chemical weapons inspector, fears that what happened last month around Damascus could set a precedent for worse to come.

"I think the urgency is the future potential. In the attack of 21 August maybe 100, maybe 200 litres of sarin were used," Col de Bretton-Gordon says.

"We believe that he [President Bashar al-Assad] has anywhere between 400 to 1,000 tonnes of sarin remaining, which could kill many tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of people if used. So it's the future potential that we must guard against".