Tremor from Italy amid political crisis

- Published

- comments

Days of negotiations dawn as Enrico Letta tries to avoid elections

Prime Minister Enrico Letta will try to save his government over the next two or three days but Italy is in political turmoil.

During the recent election campaign in Germany, the Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble said: "The world should rejoice at the positive economic signals the eurozone is sending almost continuously these days."

His comments attracted some criticism; after all, rejoicing seemed a touch inappropriate when some countries had youth unemployment around 50%.

Others like Mario Draghi, the president of the ECB, had sounded a different note. "I am very very cautious about the recovery," he said. "I can't share the enthusiasm ..."

It is hard to know but some of his caution may have had its roots in his native Italy.

Italian politics are never far from crisis. The political caste that inhabits the Palazzo Montecitorio revels in intrigue. Italy has had over 60 governments since the World War II.

For a long period the comings and goings of prime ministers passed without much comment. Not any longer.

Italy is the third largest country in the eurozone. It has debts of 2 trillion euros and is the world's third largest bond market. It remains true that despite the European Stability Mechanism (the eurozone's giant rescue fund) that Italy is too big to be bailed out. The country is still in recession; the longest since World War II.

Seven months ago Italy fought an inconclusive election campaign. There was no clear winner. President Giorgio Napolitano, mindful that the markets could turn against Italy, helped forge an unlikely coalition between the left and the right.

Crying out for reform

Suddenly the Partito Democratico - the social democrats - were in partnership with Silvio Berlusconi's People of Freedom Party.

Italy was crying out for reform. It had a political system that did not function with an over-paid political class. (At the election the comedian Beppe Grillo had won over 20% of the vote on a platform to dismantle political corruption.)

Under the previous Prime Minister Mario Monti there was an attempt to free up the labour market but more radical reforms were needed. A start had been made on clamping down on tax evasion but often the actions seemed like high-profile stunts; pulling over Ferrari owners and asking them to explain how they afforded their vehicles.

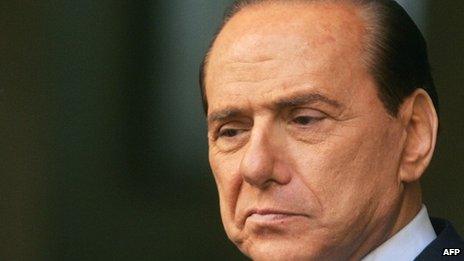

Berlusconi pulled his ministers out of the government

Above all Italy needed growth. The economy had been flat-lining for a decade and had racked up huge debts. From the start the new coalition was a fragile marriage, marked by political bickering.

There were uneasy compromises and differences of substance. Berlusconi and his allies fought hard against a property tax but, without it, there was a 5bn euro hole in the finances. Other measures, including an increase in VAT, were needed if Italy was to meet its spending commitments.

Whatever the disagreements, Berlusconi seemed to understand that the voters wanted stability and had no appetite for another election.

Strains

A strained relationship soured after Berlusconi's conviction for tax fraud was upheld by the Supreme Court at the start of August. He faced expulsion from the Senate, house arrest for a year and a ban on holding public office.

For the past two months his supporters have been trying to find a way around these penalties. There were numerous threats to bring down the government, although it was never clear how that would help Berlusconi. At times the Letta government seemed paralysed.

At the end of last week Mr Letta concluded no further legislation could be enacted unless the political crisis was resolved. He decided to hold a vote of confidence.

A committee of the Italian Senate will decide on Berlusconi's expulsion this week

Berlusconi did not want that and urged five of his ministers to resign their cabinet posts, so bringing down the coalition. Mr Letta called it ' a crazy gesture" to cover up Berlusconi's personal affairs. In his view it had nothing to do with opposition to the increase in VAT.

The future is now uncertain. Italian ministers are wary of the response from the markets. Some say if there is a long period of instability then the credit ratings agencies will downgrade Italy.

President Giorgio Napolitano says that he will only dissolve Parliament "as a last resort". He is exploring whether another coalition can be scrambled together. Silvio Berlusconi wants a vote "as quickly as possible". On his 77th birthday he seems determined to bet his future on increasing his influence at the polls.

Risky

It is a risky bet. He may even struggle to hold his party together. Some of his ministers opposed the collapse of the coalition.

Almost certainly there will be days of attempted deal-making and a vote of confidence. Italy's Labour Minister Enrico Giovannini said: "If instability were to persist and affect the eurozone, then international authorities could put much stronger pressure on national authorities".

It was a warning that Brussels and Berlin could start flexing their muscles if the euro-zone crisis returned.

Italy - as it has been for the past year - is protected by Mario Draghi's promise to do whatever it takes to defend the euro. Those words, never tested, have kept the markets at bay, unwilling to bet against the central bank. Mr Draghi will be watching to see whether last year's promise still deters the markets.

It has been said many times before that we are witnessing the final act in Silvio Berlusconi's career. His political influence is on the wane and it may just be that the voters are no longer willing to risk stability as part of a battle over his legal convictions.

Yet once again the future of Italy is tied into the personal drama of the man who likes to call himself Il Cavaliere, but if the markets turn against Italy, Berlusconi and his allies could yet be forced into making a compromise.