Lampedusa disaster: Europe's migrant dilemma

- Published

Lampedusa: Migrants risk their lives to reach Italy and start a new life

The migrant boat disaster off Lampedusa has highlighted Europe's struggle to deal with boatloads of migrants - many with legitimate asylum claims - heading across the Mediterranean from North Africa.

For years the tiny Italian island - closer to North Africa than Italy itself - has been the destination for many African migrants fleeing poverty, conflict or persecution.

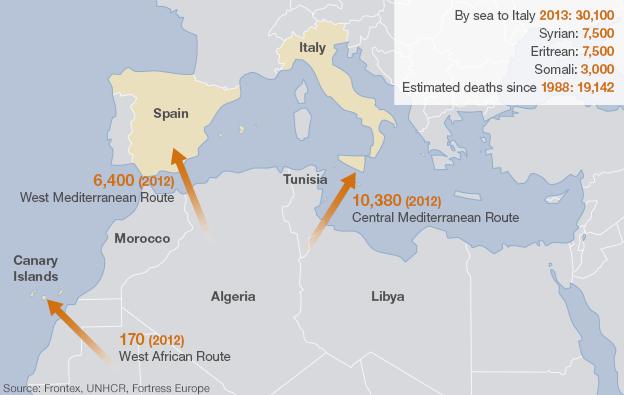

Between 1 January and 30 September this year, 30,100 migrants reached Italy on boats from North Africa, the UN's refugee agency UNHCR says. The biggest groups were from Syria (7,500 in total), Eritrea (7,500) and Somalia (3,000).

Both Syria and Somalia have been ripped apart by war, while in Eritrea thousands are either imprisoned on political grounds or face conscription into the army.

Under international law refugees fleeing persecution have a right to asylum, but when hundreds of migrants come ashore the authorities have the difficult task of identifying the genuine asylum seekers. Often they lack papers to prove their nationality or place of origin.

Lampedusa is overburdened with migrants - the island's normal population is just 6,000 and its migrant reception centre has a capacity of just 250. The capacity was reduced after a fire there in 2011.

Reception centres in Sicily and mainland Italy are better equipped, but "there is always a need to enlarge the centres because the system is under a lot of pressure now", Federico Fossi of the UNHCR in Rome told the BBC.

He said the Lampedusa centre provides basic help for migrants - food, clothes and medical attention, including psychological care. Many have survived ordeals at sea, or at the hands of ruthless people-traffickers, and are traumatised by that and the abuses they have fled in Africa or the Middle East.

Libya hotspot

The UNHCR has urged Italy to transfer Lampedusa migrants from the centre there to others in Italy after 48 hours maximum. It has welcomed an Italian plan to expand those centres to a capacity of 16,000, from the current 3,000.

"Italy needs more money from the EU - this year we are witnessing a large number of arrivals, but every year in the summer we have a peak and we have to be ready for that," Mr Fossi said.

The migrant influx is a headache for struggling Italy at a time of budget cuts aimed at reducing the country's colossal debt burden.

The EU's border agency Frontex says "the institutional capacity to tackle irregular migration in North Africa remains limited" and "Libya is of the biggest concern in this respect" because Libya remains plagued by violence, kidnappings and fragmented institutions.

In its report on illegal migration to the EU in 2012 , externalFrontex said Libya was the main departure point for migrants heading across the Mediterranean to Italy.

But in 2011 there was a surge in migrant boats arriving from Tunisia, because of the Arab Spring uprising which toppled the country's president. More than 64,000 Tunisians came ashore in Italy and Malta that year.

The exodus from there dropped sharply after September 2012, when Tunisia agreed to take back up to 100 Tunisians per week from Italy.

Now Frontex and the UNHCR are worried about a marked increase in the numbers of Syrians arriving in overcrowded boats after days at sea in the Mediterranean.

In 2011 Italy housed thousands of Tunisian migrants in tents near Taranto

Michal Parzyszek, a spokesperson for Frontex, said 2012 saw the biggest number of asylum claims in the EU since 2005 - a total of 272,208.

Frontex is helping Italy to intercept migrant boats, but the two EU operations in the southern Mediterranean have limited resources - a total of four ships, two helicopters and two planes, Mr Parzyszek said.

The Tunisia emergency was followed by the Libya emergency, when thousands of African migrants fled the war which eventually crushed Col Muammar Gaddafi's regime.

According to Mr Fossi, the 2011-2012 wave of migrants from Libya consisted mostly of Africans who had been working there and were economic migrants, rather than people fleeing persecution.

The Libya exodus was a new phenomenon - the migrant boats from Libya had dwindled to a trickle under a deal between Gaddafi and former Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Italy had helped Gaddafi to prevent the boats leaving Libya's shores.

Many migrants who reached Italy from Libya have since moved on to other EU countries. In May this year German officials accused Italy of giving African migrants up to 500 euros (£420; $680) each as well as Schengen zone visas, enabling them to leave Italy and head north.

Schengen visas allow holders to travel to most EU countries without having their passports or other documents checked at the border.

Italy gave the migrants some money to help them integrate after the Libya emergency was declared over at the end of 2012, Mr Fossi told the BBC. The migrants had to leave the reception centres, but it was not official policy to encourage them to leave Italy, Mr Fossi said.

Heading north

For many migrants the goal is to travel north in the EU, for example to Scandinavia, the Netherlands or UK, where they hope to find jobs and less hostility from anti-immigration groups.

Nigerian refugee on living homeless in Germany

Greece, Italy and Malta have complained that the EU's current asylum system puts an unfair burden on them.

Under the EU's Dublin II Regulation , externalasylum requests have to be handled by the country where the asylum seeker first arrived in the EU.

Some EU countries, including Finland and Germany, have stopped sending asylum seekers back to Greece because the country's reception centres are overcrowded and Greek officials have said they cannot cope with the numbers.

Greece's land border with Turkey was the main entry point for illegal migrants entering the EU, but the numbers dropped sharply there after Frontex sent police to help Greek border guards in 2010.

However many migrants, including Syrians, are still arriving on Greek islands by boat.

The Dublin II Regulation is under review, along with the rest of the EU's asylum policy, as the migration issue has become divisive in Europe and worries many voters.

The EU's Home Affairs Commissioner, Cecilia Malmstroem, has said , external"there is a strong need for a common European asylum policy", as 90% of asylum seekers are taken in by just 10 EU countries.

"That means that 17 countries could do much more...

"Equally, member states differ very much in the way they assess asylum requests. In fact, the situation is extremely arbitrary. The recognition rates differ seriously: for Sudanese asylum seekers the rate is 2% in Spain, whereas it is 68% in Italy.

"Such disparities are not acceptable in an EU where we have signed the same international conventions and unite around the same values," she said.