On Russia's controversial Arctic oil rig Prirazlomnaya

- Published

The BBC's Daniel Sandford reports from onboard the Prirazlomnaya oil platform which was targeted by Greenpeace activists.

Remote and buffeted by icy waves, the Prirazlomnaya oil rig in the Arctic is the focus of a bitter dispute between Greenpeace and the Russian government - now an international court case.

The journey to the rig starts in Arkhangelsk, one of Russia's historic northern ports. From there it is a two-and-a-half hour flight in an old Soviet propeller plane - an Antonov 26-100 - to the tiny settlement of Verandey, where the oil companies have built a small airstrip by the shore of the Arctic Ocean.

From Verandey to the offshore oil platform is a half-hour helicopter ride, if the weather is good. But there was low cloud the first day we were there, so there were no helicopters and we spent the night in oil-workers' accommodation before trying again the next morning.

When we made the flight the helicopter was an old Mi-8, but the safety equipment was good. We were all given survival suits for the journey, just as you would find in the North Sea.

Soon we left the flat swampland behind and were out over the Pechora Sea.

Spill risk

The Prirazlomnaya rig, when it comes into sight, is a sturdy structure set about 20m (66ft)-deep on the seabed. The visible part of the platform - the "topside" - sits on a massive concrete and steel structure. The weight of this box is what keeps it in position.

Gazprom, the Russian state-owned company which operates the rig, says that this base is so heavy that it cannot be moved, even by thick ice. The company insists that drilling here is no different just because it is in the Arctic. It says there are many rigs - off Sakhalin Island in the far east for example - which have to cope with frozen seas.

But environmental campaigners - and not only Greenpeace - insist that the Arctic is different. They say the nature here is unique. The polar bears, walruses, narwhals that live there have nowhere else to go. They warn that the Arctic Ocean only has two narrow entrances - one by Iceland and the other by Alaska. That means there is little mixing with other seas, so any oil spill would not disperse. Then there is the cold.

Igor Chestin, chief executive of the environmental group WWF Russia, warns that because of the low temperatures an oil spill in the Arctic could be catastrophic.

"If you look at oil spills which happen in tropical waters, normally within a few years you don't find the oil anymore," he said, "because there are bacteria which actually absorb the oil and the oil disappears.

"But if you look at the northern environment, and for example the famous Exxon Valdez accident near Alaska, you still find the oil there. It's still poisoning the environment 24 years after the accident happened. It's still there. It didn't disappear - there are no micro-organisms which can absorb the oil."

He says that an oil spill that might disperse in three years in warmer waters might take 100 years to disperse in the Arctic.

"Not a single oil company currently has the technology to deal with an oil spill under the ice. Some of them know how to collect oil from the surface of the water, or from the surface of the ice, which is like land. But under the ice? There are no technologies which can deal with that, and that means that the oil can spread over the place."

The wellhead is encased inside the rig, protected from the harsh weather

Fire hoses

In response Gazprom claim they have done everything they can to prevent a spill. The shallow waters mean the wellhead is actually inside the rig. They have a sophisticated cut-off system on the hoses which will offload the oil into tankers. It detects any movement by the tanker, if it is pulled away by ice for example. If there is too much movement it stops the flow of oil.

Gazprom also insists that it could cope with a spill under the ice. It says two icebreakers are near the rig at all times, which could smash the pack ice and allow modern skimmers to clean up the oil.

The workers on the Prirazlomnaya have been targeted by Greenpeace two years in a row. This year they were ready. The chief of the platform, Artur Akopov, showed us his defences - the fire hoses that his crew used to spray the activists who were trying to tie themselves onto the rig.

It was used to deter the activists, and to make the side of the platform more slippery, and so more difficult to climb, he said.

The campaigners had put his oil rig and the environment at risk, he claimed.

"By coming so close Greenpeace could have damaged the base of the platform. When they threw up their equipment they could easily have hit somebody. Or they might have ruptured one of the pressurised pipes and caused a diesel spill."

That is something Greenpeace categorically deny. They used inflatable boats, and lightweight ropes.

Dutch challenge

When the activists started climbing the platform, the Gazprom staff on the rig called their headquarters in Moscow. Artur Akopov said this was part of a pre-agreed response plan to any protest action. Within hours the FSB arrived. They are responsible for Russia's international security and borders, and are one of the successor agencies to the Soviet KGB.

The FSB officers, who wore face masks, pulled the activists off the rig, pointed guns at them, and opened fire into the water, as can be seen on video released to the media by the FSB themselves.

Given the changes in how Russia has dealt with activists in the last two years, perhaps Greenpeace should have expected a strong response.

The Pussy Riot punk protest case last year put everyone on notice that long prison sentences are now a possibility.

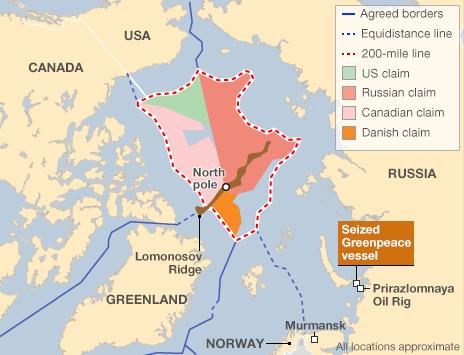

The 30 Greenpeace activists, six of them British, are now in jail in Murmansk on charges of "piracy as part of an organised group". The Netherlands - where the Greenpeace ship Arctic Sunrise is registered - has challenged the arrests. It is using the Convention on the Law of the Sea to argue that the activists were illegally detained and should be released.

"Do you think they were pirates or protesters?" I asked Artur Akopov.

"That's for the court to decide" he said.

- Published5 October 2013

- Published4 October 2013

- Published3 October 2013

- Published26 August 2013