Spain dispute over Eta militant's early release from jail

- Published

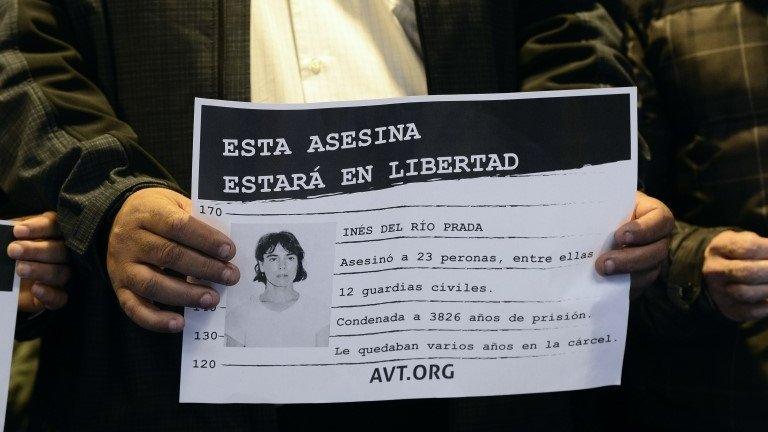

Ines del Rio (2nd right) served 26 years of a 40-year prison term

Ines del Rio was a leading member of the militant Basque separatist group Eta. In the eyes of most Spaniards she is a "terrorist", whereas her supporters controversially refer to her as a former "political prisoner".

Wording, however important, aside, Del Rio's release from a prison in Galicia this week, after serving 26 years for involvement in several bombings in the 1980s which killed a total of 24 people, has caused anger and disbelief, especially among government ministers and many of the families of Eta's more than 800 victims.

But others believe the ruling by the European Court of Human Rights is a victory for the rule of law. Eta is all but finished, but its violent legacy still looms large over Spanish politics.

'Never forgive'

On a Spanish early morning chat show this week, the voice of a 78-year-old woman, joining the programme on the telephone, echoed around the brightly lit, glitzy TV studio.

Consuelo Fenollar spoke eloquently for five minutes uninterrupted, and emotion ran through her frail voice.

"I don't understand it… all this talk of human rights," she said in reference to the Strasbourg-based European Court of Human Rights ruling that the convicted bomber Ines del Rio should be freed.

"All I ask is that if it's 40 years, they stay in prison for 40 years."

Her son, Gregorio Ordonez, a member of the centre-right Popular Party in the Basque country, was murdered by Eta in 1995.

"I will never forgive them. I'm left looking at photos all over the house, as if he's here."

The disgust of the relatives of people killed by Eta has reverberated throughout Spanish media.

"How can a woman, convicted of the deaths of 24 people, serve 26 years?" some people have asked.

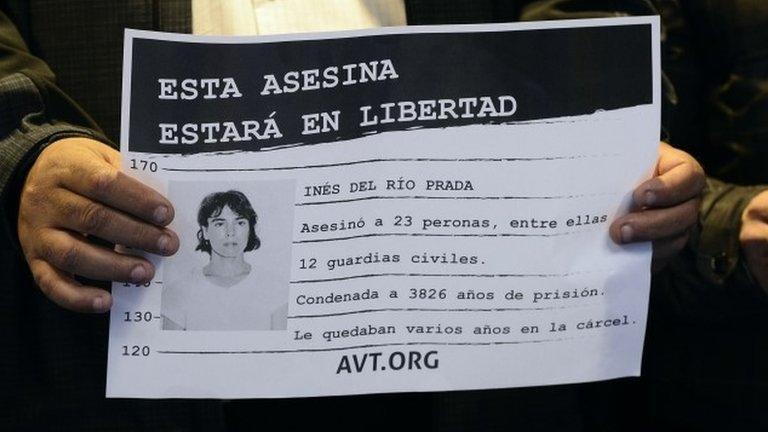

Ines del Rio's early release has caused anger and disbelief in Spain

Put simply, the answer, implicit in the ruling by the European Court of Human Rights, is that anyone who commits a crime, including terrorism offences, should be punished in accordance with the law, at the time when the crime was committed.

"At the moment when they carried out these horrific attacks, they had the right to know the punishment that would apply," says Victor Moreno, president of the Spanish Union of Penal Lawyers.

The European Court of Human Rights decided that a ruling by Spain's Supreme Court in 2006 could not be applied retrospectively.

The 2006 ruling meant that the most serious criminals, serving sentences for multiple crimes, could not be eligible for early release.

But the Strasbourg court said Ines Del Rio, convicted at the end of the 1980s, should have been set free in 2008 because under Spain's former penal code she had worked while in jail and reduced her maximum 30-year sentence to 21 years.

'Act of propaganda'

The controversy surrounding the release of Eta prisoners has been a long time coming.

Spain has no life sentence, and until 2003 the maximum jail term was 30 years.

So, given that the majority of Eta's attacks were carried out between 1970 and 1985, some of the people convicted of those killings, who qualified for early release, began to be released from prison in the early 2000s.

Public opinion in Spain at the time thought this was unjust.

Lawyer Victor Moreno describes the 2006 ruling, designed to keep Eta prisoners behind bars until the end of their full sentence, as "an act of propaganda to calm social alarm caused by the release of Eta prisoners".

Ines del Rio's supporters believed she was a political prisoner

He and other lawyers believe it is now "inevitable" that other convicted criminals, including dozens of members of Eta, could now be eligible for release, and that is causing further unease.

Juan Moscoso, an opposition Socialist MP, believes the decision by the European Court of Human Rights, however difficult for the relatives of Eta's victims, is a "victory for the rule of law".

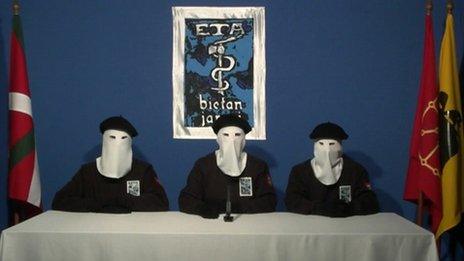

"The Eta that we suffered… no longer exists. It has been defeated. It will not return," said Spain's Interior Minister Jorge Fernandez Díaz following the Strasbourg ruling.

Eta called a permanent ceasefire in 2011 and over the past two years 58 alleged members of the group have been arrested.

It's true therefore that Eta is increasingly weak and irrelevant in Spain today.

That said, the case of Ines del Rio, and the likely release from prison of more members of Eta in the coming weeks, shows how the shadow of its past looms large over Spanish politics.

Juan Moscoso and other politicians on the left of Spanish politics believe it is time to end the policy, under which the majority of the 600 or so Eta prisoners in Spain are kept in jails outside the Basque country and in many cases in faraway parts of Spain or in France.

They think that if Eta prisoners were moved closer to their relatives, it's likely that the militant Basque group would disband and hand in whatever arms it still has.

But the position of Spain's ruling Popular Party is unflinching.

"The prisons policy of the government is not going to change," said Spain's interior minister.

The PP has always taken a very tough line over Eta. It is something its voters expect, and the PP-led Spanish government says it is not willing to negotiate with what it calls "terrorists" even though dozens more of them could soon be free to walk Spain's streets.

- Published22 October 2013

- Published21 October 2013

- Published20 October 2011

- Published16 May 2019