Kosovo violence leaves election in tatters

- Published

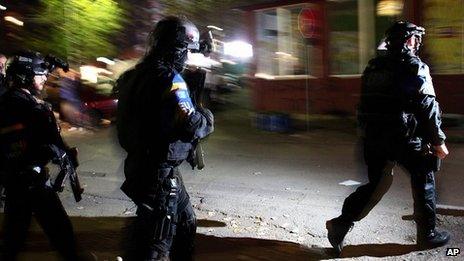

EU (Eulex) police arrive at the vandalised polling station in Mitrovica

It was a local election that was supposed to have an international impact. But it started with farce and ended with chaos - amid tear gas, smashed ballot boxes and accusations of "dark forces" at work.

The votes from the majority ethnic-Serb, four most northern municipalities in Kosovo were supposed to have been tallied up on Sunday evening.

But by Monday morning they remained uncounted, and it was unclear whether the abruptly curtailed election could be declared valid.

Trouble had been brewing ever since Serbia agreed to normalise relations with the Republic of Kosovo in April. That was a key condition for the European Union to approve the start of membership talks with Belgrade - but it was greeted with dismay by the 50,000 or so ethnic Serbs who live in Kosovo's four northern municipalities.

The deal spelled the end of the "parallel institutions" in which Belgrade funded healthcare, education and judicial systems for the North Kosovo Serbs. Instead there would be an association of Serb municipalities within the Republic of Kosovo.

The municipal polls were supposed to make that possible. The Serbian government said the ethnic Serbs could only benefit by electing mayors and councillors who would be recognised in Pristina as well as Belgrade.

It was never likely to be an easy sell. The Serbs in North Kosovo have been steadfast in their refusal to recognise the legitimacy of the government in Pristina. And for that matter, despite the normalisation agreement, Belgrade still says it will never recognise the Republic of Kosovo's unilaterally-declared independence.

But Serbia was under pressure to keep its EU membership ambitions on track by showing that it was co-operating with the elections. So it tried to persuade the North Kosovo Serbs to vote.

It formed a list of candidates under the banner "Srpska" (Serbian) - and promoted it with posters of Serbia's most powerful and popular politician, First Deputy Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic. Then it started appealing to people's pockets - suggesting a high turnout of Serb voters was the best way to ensure Belgrade continued payments to public sector workers.

As polling day approached, the arm-twisting became ever more explicit. The implication was that if the people of North Kosovo were so proud to be Serbs, then they should follow the instructions of their government - or pay the price.

Observers quickly left the polling station in Mitrovica after it was attacked

"If you don't believe your own country, then don't believe your own pocket," said Danijela Vujicic, a senior member of the "Srpska" list in North Mitrovica, the largest municipality in North Kosovo.

"If you don't want to accept your own country's message, please be good enough not to go and get a salary from the Republic of Serbia every month."

But there were other arm-twisters at work. A campaign to boycott the vote was particularly well-organised in North Mitrovica, where the "No" banners and posters far outnumbered the publicity for any of the candidates.

One of the boycott organisers, Nebojsa Jovic, said no-one was listening to the people whose lives would be most affected by the new system.

"I invite all sides - the Serbian government, international community and Kosovo institutions - to understand the reality on the ground. Ninety-five percent of Serbs don't want to live in the state of Kosovo. We demand the same rights that the ethnic Albanian people had when they declared independence from Serbia."

On election day, it seemed the boycott campaign was poised to score a spectacular success. There was a farcical start when some of the ballot boxes marshalled by the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) were not ready for the early voters. But after that the polling stations in North Mitrovica were extremely quiet.

With two hours to go before they shut, it seemed that very few Serbs had voted - raising the possibility that an ethnic Albanian mayor might be elected in North Mitrovica. That would have been an untenable - if darkly comic - proposition. More importantly, the whole idea of an association of Serb municipalities would have been in tatters.

Staff attacked

But an incident at a polling station at St Sava primary school prevented that scenario becoming reality. Masked intruders smashed up ballot boxes and assaulted staff.

OSCE staff made a dramatic exit from North Mitrovica in full body armour and a convoy of Land Cruisers immediately after the intrusion. They said other polling stations in North Mitrovica were also attacked - and called a halt to the vote in nearby Zvecan.

In a late night press conference, the head of the OSCE in Kosovo, Jean-Claude Schlumberger, said that "indications that the elections would be a success were obviously not acceptable news for everybody".

With no count in the four northern municipalities, no-one could claim victory - or suffer defeat. The government swiftly placed the blame for the fiasco on "extremists" - but the "No" campaigners claimed the polling station attacks were ordered when it was clear the boycott had succeeded. They condemned the incidents, and suggested the "dark forces of the official political agenda" were responsible.

Now the question is whether there will be another attempt to persuade North Kosovo's Serbs to vote in an election called by a state which they fervently believe should not exist - and to which, they insist, they will never belong.

- Published3 November 2013

- Published28 June 2023

- Published19 April 2013

- Published17 February 2011

- Published2 September 2014