Nazi trove in Munich contains unknown works by masters

- Published

Artworks were looted from occupied countries or confiscated for being "degenerate"

Previously unknown artworks by masters are among more than 1,400 pieces found in a trove of Nazi-looted art in Munich, German officials say.

As slides of the paintings were shown at a news conference, an expert said the works had been seized from private individuals or institutions.

Previously unregistered works by Marc Chagall, Otto Dix, Max Liebermann and Henri Matisse were found.

Prosecutors said the issue of ownership was still being clarified.

The total value has been estimated at about 1bn euros (£846m; $1.35bn).

Reinhard Nemetz, head of the prosecutors' office in Augsburg, said that 121 framed and 1,285 unframed works had been seized in the flat of Cornelius Gurlitt in Munich in March of last year.

It was not yet clear if any offence had been committed, he added, stressing that the legal position was extremely complex.

Investigators, he said, had turned up "concrete evidence" that at least some of the works had been seized by the Nazis from their owners or had been deemed "degenerate".

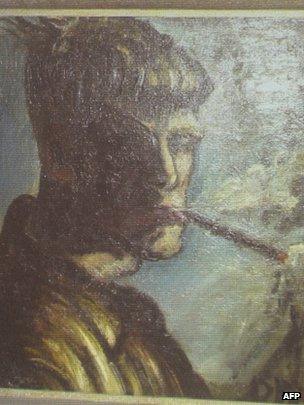

This self-portrait by Otto Dix was found

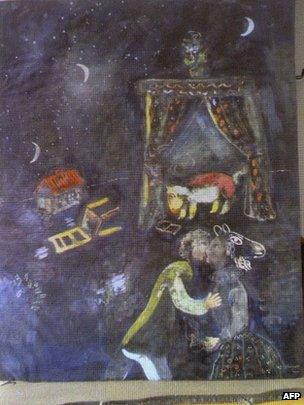

This previously unknown Marc Chagall painting was also recovered

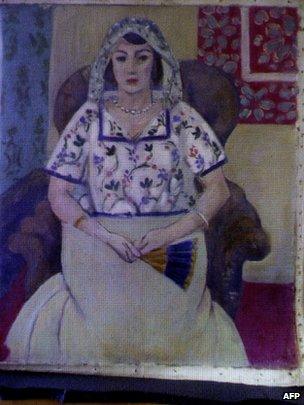

This painting was attributed to Henri Matisse

Art expert Meike Hoffmann said some of the works were dirty but they had not been damaged.

'Extraordinarily good'

"When you stand before the works and see again these long-lost, missing works, that were believed destroyed, seeing them in quite good condition, it's an extraordinarily good feeling," Ms Hoffmann said.

Art expert Meike Hoffmann: "An emotional discovery"

"The pictures are of exceptional quality, and have very special value for art experts. Many works were unknown until now."

Other artists whose works were found include Pablo Picasso and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as Canaletto and Gustave Courbet.

The paintings were found in March of last year after Mr Gurlitt was investigated for tax evasion.

The framed pictures were stacked on a shelf, like in a museum storeroom while the unframed works were piled up in drawers, said customs official Siegfried Kloeble.

According to a report by Germany's Focus magazine, Mr Gurlitt, the reclusive son of an art dealer in Munich, would occasionally sell a picture when he needed money.

"We don't have any strong suspicion of a crime that would justify an arrest," said Mr Nemetz, adding that the current whereabouts of Mr Gurlitt were unknown.

Asked at the news conference why the German authorities had taken so long to reveal the paintings, the prosecutor said it would have been "counter-productive to go public" with the case earlier.

Mr Kloeble refused to say where the artworks were being stored.

Mr Gurlitt's father Hildebrand collected early 20th Century art regarded by the Nazis as un-German or "degenerate", and removed from show in state museums.

He was recruited by the Nazis to sell the "degenerate art" abroad but also bought privately.

After the war he told investigators that his collection had been destroyed during the Allied bombing of Dresden in 1945. He also said he had been persecuted himself for having a Jewish grandmother.

Resuming his work as a dealer, he died in a car crash in 1956.

A Jewish group has questioned the length of time it took Germany to unveil the artworks and called for them to be returned to their original owners.

"It cannot be, as in this case, that what amounts morally to the concealment of stolen goods continues," said Ruediger Mahlo, speaking for the Conference on Jewish material claims against Germany.

'Justice denied'

Stuart Eizenstat, a former US ambassador to the EU, told the BBC that time was running out, and the details of the artworks should be published.

"Victims of the Holocaust are aging, even the families of those who did not survive are of an age," he said.

"It's important that this be publicised. But the longer one goes... the more difficult it is for people to prepare potential claims... Justice delayed is justice denied."

However, prosecutors say it would not be proper procedure to put things on the internet and people who want to make a claim should contact them directly.

The BBC's Stephen Evans in Munich says that descendants of owners of art taken by German forces in occupied Europe may be able to make claims.

However, there are suggestions that art taken in Germany itself may not be reclaimable because of a 30-year statute of limitations.

Mr Mahlo said that private collections of such art under the Third Reich had been almost all Jewish.

However, auctioneers have argued that at least some of the works were purchased cheaply in 1938 by Mr Gurlitt's father from a collection of state-owned art.

In 1990, Cornelius Gurlitt auctioned works for 38,250 Swiss francs (31,000 euros) in Galerie Kornfeld, an auction house and gallery in the Swiss city of Bern.

In a statement quoted by Reuters news agency, Galerie Kornfeld said: "Cornelius Gurlitt inherited the works after the death of his mother Helene. Basically this is a case of undeclared inheritance."

- Published5 November 2013

- Published4 November 2013

- Published4 November 2013

- Published4 November 2013