EU migration: Bulgaria's departing doctors

- Published

In Bulgaria (from left) Radislav Nakov, Vladimir Bashliyiski and Kamen Dimitrov would earn a fraction of what their EU counterparts make

On 1 January 2014, Bulgarians and Romanians will be able to work anywhere in the European Union as the last of their membership restrictions are lifted.

Research suggests that few will migrate abroad without a firm job offer but many Bulgarian doctors are already actively seeking work in other EU countries, particularly in Germany, Austria and the UK. Spurring them on is the hope of earning 10 times their Bulgarian salaries.

In the empty lecture room at Aleksandrovska Hospital Medical School in Sofia, newly qualified doctor Kamen Dimitrov laughs when I ask him if he is thinking about doing his Foundation Programme (houseman years/ internship) in Bulgaria.

"I've already got an invitation to study a specialism in Vienna," he tells me, "so of course I am leaving."

He shrugs. "Each person wants the best he can get for himself and I researched the possibilities in the whole of the EU - maybe I will come back to Bulgaria after my specialist training but probably I'll stay in Vienna or go to the UK."

His friends Vladimir Bashliyiski and Radislav Nakov are also thinking of leaving. A recent study by the department of social medicine and public health at the Medical University of Sofia suggests that in fact more than 80% of newly qualified doctors plan to leave Bulgaria.

"There's so much corruption in the health service," explains Dr Nakov.

"We still live under something similar to communism in Bulgaria. It sounds awful but we are losing hope in the future. Our only advantage is that we are now members of the European Union and can move abroad easily."

Dr Bashliyiski is trying to get work in a Birmingham hospital.

"I thought a lot about my choice," he says. "Really a lot. But I don't want to stay in Bulgaria. The system is rotten in Bulgaria. I don't find any light in the tunnel. I hope to find it in Birmingham or London, in Belgium or somewhere else."

'Moral choice'

In the neighbouring lecture room, Professor Maria Vlaskovska, their former tutor and former minister for public health, is doggedly setting up her projector to teach yet another set of students she knows will probably leave Bulgaria.

Vascular surgeon Dimitar Balezdrov plans to move to the UK in search of work

"Most of my PhD students have already gone abroad," she smiles wryly.

"Last term, 75 of my final year students already had places in another EU country or the US. It's a very big problem but we do our best. I just hope that they'll come back. And that more and more students will try to improve the situation here."

At the Tokuda hospital, 34-year-old vascular surgeon Dimitar Balezdrov patrols the wards in his sky-blue scrubs, checking the blood pressure of an elderly patient he has just operated on. He is only half way through a 24-hour shift and he already looks tired.

"I don't want to fight anymore," he tells me wearily. "I just want to leave. It's sad. It's a kind of surrender but I will go to the UK."

Bulgaria has the lowest wages in the EU and doctors' salaries are no exception. Dr Balezdrov earns around £800 a month (950 euros; $1,280). If he worked in the same field in the UK, he would earn £60-70,000 a year.

Young doctors like Dr Dimitrov, Dr Nakov and Dr Bashliyiski would earn about 10 times more in Germany or the UK than they would in Bulgaria.

"But it's also an ethical choice, a moral choice", insists Dr Balezdrov.

"If I stay here, sure, with so many doctors leaving Bulgaria, I could make more money. But I will have to do things I don't want to do. I will have to operate on people for money - people who don't really need operations. Yes, that's the way it is here with corruption. And if I don't do it, I won't survive as a doctor in Bulgaria."

'No guilt'

The Bulgarian health ministry is aware of the impending brain drain and insists it is doing its best to reform the health care service and to boost doctors' wages. In a written statement to the BBC it said: "Currently in Bulgaria there are changes in the legislation, creating favourable conditions for the retention of junior doctors in the country.

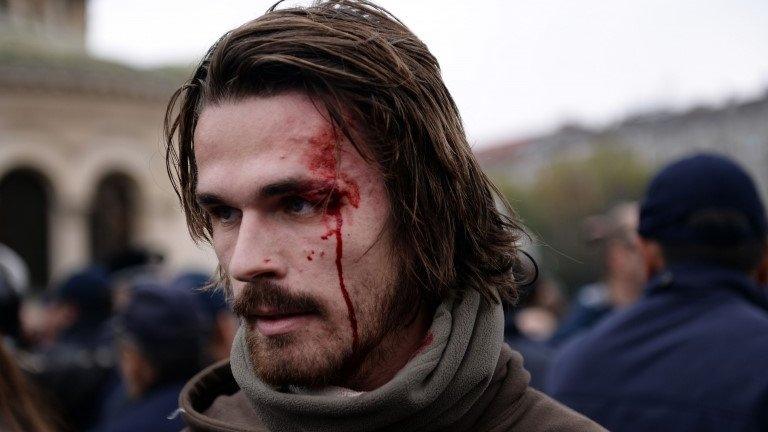

Student-led protests against corruption have continued for months in Bulgaria

"On the whole, study programmes are improving and the requirements for specialisation are becoming more accessible. Medical standards are optimising for different specialties…

"In the new budget are set parameters to increase the salaries of doctors in the psychiatric clinics and those working in the emergency medical centres."

From outside their lecture hall, loud whistles and drums sound the start of a spirited student protest against corruption.

Radislav Nakov and Vladimir Bashliyisk have regularly taken part in such marches but when I ask the young doctors if they do not have a bad conscience about leaving the country whose taxpayers have just funded five years of their medical training, they are adamant.

"I really don't feel guilty," says Dr Bashliyiski emphatically. "Because if the government doesn't support and cherish its young minds, this is the result. If things change maybe I will consider coming back. Just maybe."

Ironically, Dr Nakov is the chairman of a body termed the "foreign affairs committee of the association for the development of the medical community".

"What development?" he asks me drily.

"We are not asking for Western European salaries - but just let us live a better life by making them the same as other post-communist countries like the Czech Republic or Poland.

"In the UK when you say you are a doctor, you are respected by society and that's absolutely not true here. I think countries like Germany and the UK will welcome educated immigrants like us."

- Published12 November 2013

- Published23 July 2013

- Published20 January