Q&A: What benefits can EU migrants get?

- Published

Migration to the UK from Poland was much greater than expected after 2004

The benefits that EU migrants can claim in another EU country vary across the 28-nation bloc, but certain basic rules are enshrined in EU law.

The issue became a hot topic in the UK because in January 2014 the remaining labour market restrictions on citizens of Bulgaria and Romania were removed across the EU.

After EU enlargement in 2004 the UK experienced a far greater influx of East Europeans than had been anticipated.

Can EU migrants easily claim benefits when they arrive in another EU country?

No - there are conditions, depending on an individual's circumstances.

They can stay for three months, but to stay longer after that they have to be: in work; or actively seeking work with a genuine chance of being hired; or be able to show they have enough money not to be a burden on public services. Apart from that, evidence of benefit abuse or fraud is grounds to exclude or expel a person.

Many German farms rely on seasonal workers from Eastern Europe

If an EU migrant has permission to stay, can he or she then claim benefits?

Not automatically - a migrant still has to pass a "habitual residence test" under EU law.

The test covers factors such as the duration of the migrant's stay; their activity, including their source of income if they are students; their family status; and their housing situation. The migrant has to demonstrate a sufficient degree of attachment to the host country. The amount of time already spent in the country is not sufficient qualification in itself.

If a jobseeker satisfies the test in the UK then that person can claim Jobseekers Allowance - up to £72.40 ($116) weekly for a single person, £113.70 for a couple.

An EU migrant who is in work in the UK, or self-employed, and who passes the test, can claim housing benefit and council tax benefit. The amounts vary, depending on the local authority.

The UK applies an additional "right to reside" test, going beyond the standard EU test. The European Commission says the UK test is unfair and has taken the UK to the European Court of Justice over it. The Commission argues that EU migrant workers, who have paid UK taxes, should not be subject to the extra test in order to claim certain benefits.

Are EU migrants entitled to the same benefits as citizens of the host country?

Yes, if they are workers or self-employed - and their family members are entitled too. However, access to certain benefits can depend on the amount of time a worker has been paying contributions. So a native of the host country may have more entitlements.

Jobless migrants are not entitled to the same range of benefits - mainly those which are funded from salary contributions. Workers pay social security contributions, to cover sickness, unemployment, maternity or paternity, invalidity or occupational injuries.

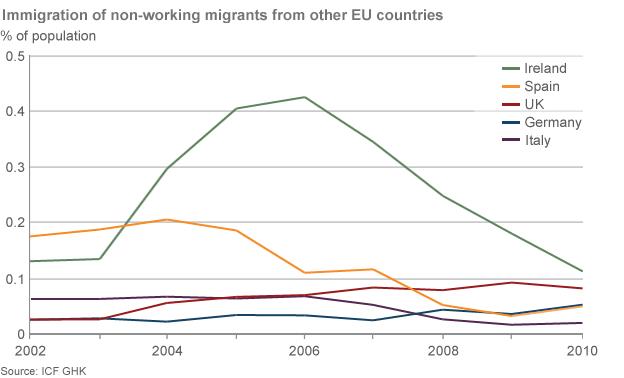

The graph above includes jobseekers. Per head of population Ireland had the biggest influx of East Europeans after EU enlargement in 2004, but the UK took in the biggest numbers. Net migration to the UK from EU states in Eastern Europe reached nearly 400,000 in 2004-2011.

Is the UK benefits system more generous than those in other EU countries?

The systems are very diverse, so comparisons are difficult.

In terms of total spending on social security per inhabitant, the UK does not rank highest. In the UK the figure for 2010 was nearly 8,000 euros (£6,660; $10,880), the EU statistics agency Eurostat reports. In France and Germany it was nearly 9,000 euros, while in Denmark and the Netherlands it was above 10,000. At the other end of the scale, spending in Bulgaria and Romania was below 2,000 euros.

The Open Europe think-tank, campaigning for radical reform of the EU, says some countries have more flexibility than the UK in the area of "social assistance" benefits. Such benefits - targeting people in need - are usually means-tested and come out of general taxation, rather than salary contributions. In the UK, income support and housing benefit fall into that category.

In the UK, a bigger portion of welfare is funded by the state than is the case in Poland, France, Germany or the Netherlands. In those countries, more is funded from individual and employer contributions. In other words, more benefits are linked to previous earnings.

On the other hand, in several countries, including the Republic of Ireland, Sweden and Denmark, the share of state funding is higher than in the UK.

In Germany, there is a two-tier welfare system - part based on contributions, part non-contributory. An EU migrant made jobless in Germany would get up to 70% of current salary in the first year of unemployment. After that, the unemployed go onto a non-contributory system called Hartz IV. Germany has objected to paying those benefits to EU migrants who have not made sufficient contributions through work. But that policy has been challenged in the courts.

In Spain, welfare payments depend to a large extent on where you live as payments are handled regionally, rather than centrally. In Madrid there is a two-year residency test for RMI, which is paid to unemployed jobseekers. The benefits system in the Basque Country is rather less restrictive.

In Bulgaria, the EU's poorest country, you do not qualify for unemployment benefit unless you have been working for at least nine of the last 15 months.

What about healthcare?

Under EU law, EU citizens visiting for short periods can receive basic and emergency care with a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC).

It is the host country's responsibility to get the treatment costs reimbursed by the health service in the patient's home state. The UK government says the National Health Service needs to do more to get such costs reimbursed.

The UK is not the only EU member state to have a free, "universalist" health service, funded by taxpayers. Scandinavian countries have similar models, but most EU countries fund healthcare through medical insurance systems.

At least 400,000 Britons live in Spain full-time, a quarter of them pensioners, and they have free access to Spanish local doctors. The Spanish health service recovers the cost of their hospital treatment from the NHS - unless they have permanent residence status, in which case Spain pays for it.

.gif)

- Published28 November 2013

- Published27 November 2013

- Published14 October 2013

- Published16 August 2013