Waiting for the dead of Lampedusa

- Published

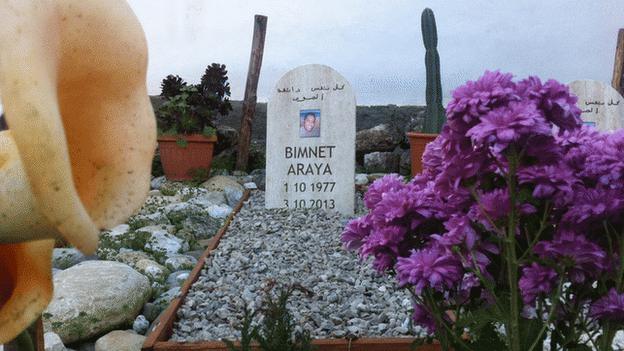

Bimnet Araya's grave bears his name - others have only numbers

Relatives of those who died in one of the worst boat disasters off the shores of Europe in living memory are still waiting to be allowed to take their family members for a proper burial. A total of 366 people - mostly from Eritrea - died when the boat carrying them sank close to the Italian island of Lampedusa.

Church bells sound on the late afternoon breeze as Alem Araya walks through the cemetery in the little Sicilian village of San Biagio Platani.

"Emotional, yes," he says quietly. "It's not easy."

Mr Araya, 49, an Eritrean who has lived in Germany for much of his life, passes row upon row of ornate tombs, pictures of the Virgin Mary and Jesus looking down on him as he heads for the open ground at the bottom of the hill.

There, against a wall, are five basic graves, each with a headstone.

'All just young'

He stops in front of them, crosses himself, bows his head slightly and then, after a moment, breaks down in tears. His sobs echo across the grave of his brother, and the four others lying now at his feet.

"They were all together in the boat from Libya to Lampedusa," he says quietly. "Four persons from Eritrea and one person from Ethiopia. All of them just young people."

His brother Bimnet was 36 years old. A former basketball player for the Eritrean national team. He had studied at university in London.

"He left to make another life in Europe. But that life ended in Lampedusa," Mr Araya says, wiping away a tear.

So Bimnet, like many others, crossed the border into neighbouring Sudan. From there he travelled to Libya to take a boat to Europe.

"I was against this travel to Libya," his brother says.

"I tried to bring him legally from Sudan to Germany. But he has many friends, and they were ready to go to Libya. He decided in a short time: 'No I cannot stay here - I will also take my chance with them'."

Visas denied

There was no morgue big enough to store the bodies from the shipwreck, so for days they decayed in the heat of a hanger at Lampedusa's airport.

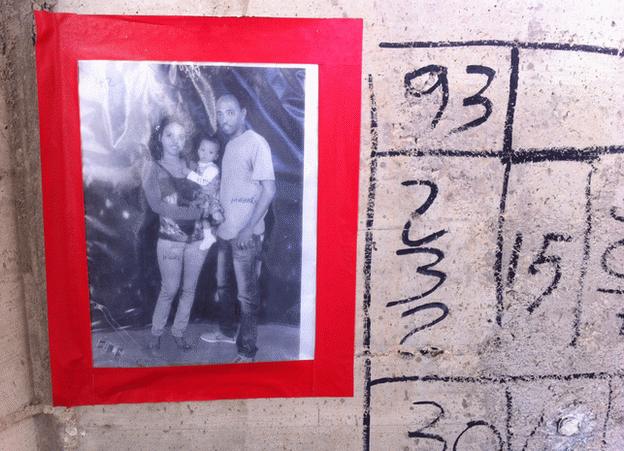

A photo marks the grave of Fthi and her parents

Then they were shipped off to Sicily and buried - stored essentially - at cemeteries across the island.

Most of the dead are identified only by a number - either placed next to their grave or etched into the concrete behind which they are entombed.

Some graves have been decorated with pictures of those buried inside. Next to one is a picture of a young couple and their baby girl. Number 93. Her name is Fthi.

Most likely the pictures were placed there by relatives who live in Europe who can visit, and who have been able to find their family members.

So far though - because there has been no proper identification process - they have not been able to take the bodies home for a proper burial. And most relatives cannot come - they cannot get the visa to leave Eritrea.

A massive DNA-testing programme is needed. In a clinic in the southern Sicilian town of Agrigento, Alem Araya is one of the first to have blood and a saliva swab taken.

He hands over 150 euros (£124; $203) to pay for the test, after struggling to make himself understood by the assistant who does not speak much English.

Some graves have only numbers

He has the money and resources to do this, and because he is a European resident he can come to Sicily. Most relatives of those who died cannot.

But even for him it has been very difficult to get this far.

'Forgotten'

"The problem is the Italian government is not ready to help us," he says. "The situation is very, very difficult and they know that. But I don't think they are ready to help me quickly."

When the boat sank, Italy's prime minister promised to do all he could to help the relatives.

Yet two months later, at the anonymous graves with their scratched in numbers, it is as if they have been forgotten, the evidence of Europe's worst maritime tragedy in years literally buried away.

The Italian government would not comment on Alem Araya's allegations.

He believes local officials are doing all they can, and yet for him and for his elderly mother, who is waiting back home in Eritrea for her son's body to be returned, it is all too painfully slow.

"For my mother when I say one more day, it's for her one year of pain," he says.

"It's too long. And not only for my mother, for all of the victims who have family in Eritrea and elsewhere. They are waiting for all the bodies to go back to Eritrea."

Up on a promenade close to the centre of Agrigento, he leans on a railing, the sun's light bouncing up off the Mediterranean Sea far below him.

"It's hard," he says. "Very, very hard to think about the situation in Lampedusa. I can't forget it."

His voice trails off, as he looks out at the sea. The sea in which his brother died.