Pope Francis gives Catholic Church gentle revolution

- Published

In just nine months Pope Francis has almost trebled the size of crowds attending papal audiences, Masses and other events in Vatican City.

Before 13 March last year, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was expecting to spend his next Christmas in retirement - in an old people's home in the Buenos Aires district of Flores, where he was born 77 years ago.

But now he carries the hopes and fears of more than a billion Roman Catholics.

What explains this suddenly renewed interest in Catholicism? What need is Pope Francis meeting in people?

Nine months ago the Church was beset by allegations of scandal and mismanagement in its bureaucracy and its bank, its reputation besmirched by the sexual abuse scandal.

"The dominant narrative about the Catholic Church today is 'rock star Pope takes the world by storm'," says John Allen of the National Catholic Reporter.

"If that's not a revolution, at least at the level of perception, then we have never seen one."

Compassion

The revolution has been forged in gestures, such as the Pope's decision to include a Muslim woman when he washed the feet of young offenders last Easter, and his instinctive hug for a man whose face was badly disfigured by disease.

His refusal to live in the papal apartment or to wear the regal clothes that go with his office has also caught the public imagination.

So has the way he picks up the phone to call people out of the blue.

Sister Teresa, a nun of the Daughters of St Anne, was teaching a class of 11-year-olds at her school in Casal di Principe when her mobile phone rang.

"I saw a very long number," she says. "A voice said, 'I'm Pope Francis', and I said, 'You must be joking, I don't believe it'. He laughed, and said 'I AM, Father Bergoglio'."

Pope Francis called to bless the nuns' campaign against the dumping of toxic waste, touched by photographs they had sent him, each one depicting a mother holding the picture of a dead child.

She said the conversation had left her feeling "serene, because the Pope is thinking of us and loves us and is not leaving us alone".

But not all Roman Catholics welcome Pope Francis's new approach.

Vatican bureaucracy

Some traditionalists say his unwillingness to talk much about the Church's beliefs on issues such as abortion, contraception and homosexuality cedes too much ground to secular values.

Kishore Jayabalan, director of a Christian research organisation, the Acton Institute, says others are uneasy about the effect of the Pope's humble style.

"Some of the more traditionalist critics of Pope Francis are worried about the less regal style of the papacy - the Pope, as a rule, has the trappings of a monarchy," he says.

But the "Francis effect" will not be limited to changes in style and emphasis.

Pope Francis has recruited eight cardinals to help him reform the Vatican bureaucracy and has acted to address mismanagement in the Vatican bank.

Now the Pope could be considering a far bigger step.

"I think the most profound change the Pope is aiming for is revamping the Synod of Bishops," says Robert Mickens, of Catholic journal The Tablet.

"It was set up in the 1960s and has been used to rubber-stamp whatever the Pope wanted to do.

"This Pope wants to expand it, to give it real power and use it to help him rule the Church and eventually to give them the authority to make decisions themselves. That would be a revolutionary change."

The Pope has also suggested that the power and authority concentrated for centuries in the papacy might be devolved to some extent, to conferences of bishops in countries round the world.

"Now we have a pope saying 'we can trust local bishops… to make the decisions,' says Mr Allen.

"In the long run, that shift of power from the centre to the periphery, if Francis pulls it off and makes it real, is a historically significant development in Catholic life."

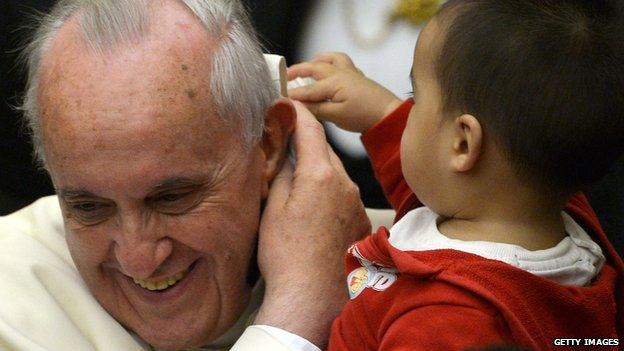

Pope Francis has been praised for his warmth towards children and the poor

But there could be dangers in loosening the reins on a Church of more than one billion people present in widely diverse societies across the world.

Fr Joseph Kramer, priest of The Most Holy Trinity of Pilgrims church in Rome, says the papacy is needed for practical reasons, to unify clergy who have a propensity to disagree.

"You run the risk of schisms and divisions and arguments", he says.

"This unfortunately happens in Eastern [Orthodox] churches and Protestant denominations, where you don't have a central authority."

There could be other reforms - perhaps an end to the ban on divorced and remarried Catholics from taking Holy Communion, perhaps a greater role for women in the Church.

But there will be no change to conservative teaching on fundamental issues such as homosexuality, euthanasia or abortion.

So can Pope Francis succeed in rebuilding Christian faith by simply changing the conversation, or the "narrative" about Catholicism, without real reform of its teaching?

John Allen sees the Francis pontificate as a kind of laboratory experiment.

"There has been a trend in progressive Catholicism that says we don't need to change the doctrines to recapture public interest," says Mr Allen.

"We need people to see the real commitment to human flourishing that is ultimately at the core of these doctrines. What we are going to see on Pope Francis's watch is that he will put a beguiling human face on to the classic message."

The change in tone under the new Pope, it seems, is aimed at a secularising society, one which at least one commentator sees as "post-Christian".

"The Christian epoch is gone, it's all over and Pope Francis knows that," says Mr Mickens of The Tablet.

"A Jesuit leader said the Church has been giving answers to questions people aren't asking. Pope Francis is trying to give answers to questions people are asking - why is my grandmother in a home? Why is there no-one to care for her? Why can't my son find work?"

Pope Francis now has the world's attention, fleeting and fickle though it may be, and a rare opportunity to make significant changes.