Q&A: Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Russia

- Published

December 2010, behind glass in a Moscow courtroom

Mikhail Khodorkovsky went from being Russia's richest man to its most famous prisoner in a life that has to some extent mirrored the changes in modern Russia.

The former oligarch was suddenly pardoned by President Vladimir Putin and flown to Germany after spending a decade in custody on charges some believe were fabricated to block any serious political opposition to the strongman of the Kremlin.

How rich was richest?

.gif)

October 1992, at home with his family

Forbes magazine put his net worth at more than $15bn (£9.1bn) before his arrest in 2003. By comparison, today's richest Russian citizen, Alisher Usmanov, is valued at $17.6bn, external.

In the early 1990s, other Russians watched their savings eaten by inflation and the assets of their state sold off at bargain prices to those in the know.

Khodorkovsky, a former star of the Moscow Communist Youth League, was making his first millions through his own bank, Menatep.

The really big money came in 1995 when he bought the Yukos oil company at the knockdown price of $350m.

When was the Kremlin good for business?

June 1998 (first from right), waiting to meet Boris Yeltsin at the Kremlin. Other tycoons present: Vladimir Gusinsky, Mikhail Fridman and Vladimir Potanin

Khodorkovsky had been close to the centre of power since Soviet days, when he worked as an aide to the last prime minister of the USSR, Ivan Silayev.

In the chaotic years of Boris Yeltsin's rule, Khodorkovsky became one of the oligarchs, a small group of fabulously rich tycoons who kept close to the Kremlin as they built their businesses.

They bankrolled Yeltsin's re-election in 1996 - arguably the last presidential election in Russia where voters were offered a real choice.

Meanwhile, all around them, ordinary Russians watched the continuing decline of their living standards and their country, shaken by a disastrous war against separatists in Chechnya.

Where did it all go wrong?

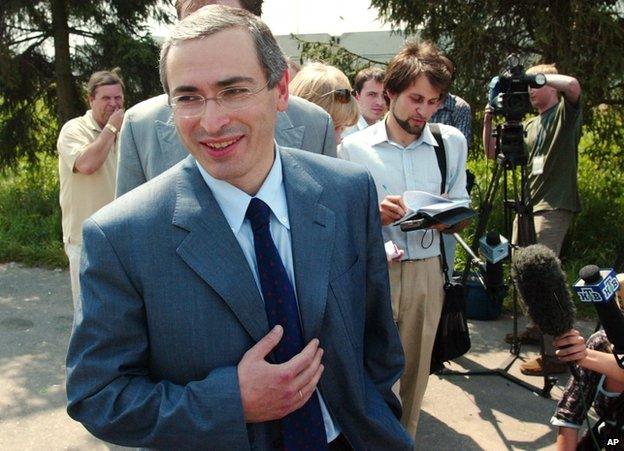

July 2003, by the end of the year he will be in custody

When Vladimir Putin won the 2000 election, he set about rebuilding a strong state that paid people's wages and pensions on time, and he restored an order of sorts in the war-torn south.

But there would be no going back to communism and tycoons who kept out of the new leader's political path were tolerated, even as Yeltsin's political reforms were rolled back.

Khodorkovsky is credited for his efforts to modernise Russian business practices at that time, introducing unprecedented transparency to the accounts of Yukos.

Sensing a return to one-party rule, he also funded liberal opposition parties. In February 2003 he openly sparred with Mr Putin at a televised meeting, accusing government officials of taking huge bribes.

That October, he was arrested at gunpoint and charged with tax evasion.

Six months later, Mr Putin was re-elected president, increasing his share of the vote from 53% to 71%.

What has changed in a decade?

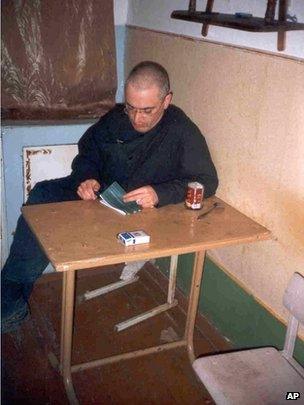

November 2005, in his YaG-14/10 prison camp, Siberia

Convicted of tax evasion in 2005, Khodorkovsky was sent to prison. The billionaire found himself in a Siberian prison camp, external where inmates could expect to earn $0.81 a day for their labour.

Passionately denying the charges against him, he devoted his energies to clearing his name, his campaign backed by advocates worldwide.

Even when he was tried and sentenced to a second term in 2010, this time for embezzlement and money-laundering, he persevered, releasing statements from his new prison near the Arctic Circle.

In the outside world, Vladimir Putin and his allies saw their iron grip on Russia briefly loosened in 2011, when indignation at corruption boiled over into the biggest street protests since Soviet times.

Mr Putin reasserted his authority and key figures in the protest movement were hounded through the courts, on charges again seen by many as politically motivated.

What now?

December 2013, reunited in Berlin with his parents Marina and Boris, and son Pavel

After arriving in Germany, he said he would not return to Russia until he was confident he would be able to leave it again. Before his release, there had been rumours of new charges being drawn up to keep him in prison even longer.

He stressed he had been released on humanitarian grounds, and that the issue of his guilt had not been discussed, but his conviction still stands.

Khodorkovsky's fortune apparently crumbled long ago, with his business empire effectively seized by the state, but the former oligarch may have amassed moral capital in the eyes of some as a victim of injustice.

However, he said in Berlin he would stay out of Russian politics and instead work as an advocate of political prisoners in Russia and other countries.