'Meat Atlas' charts a changing world of meat eaters

- Published

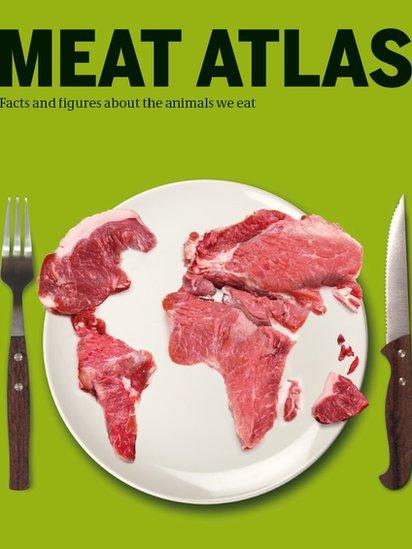

If anything is going to put you off eating meat, a map made out of a raw bloody steak might just do the trick.

That is the cover of the Meat Atlas, external, a yearly publication by the Heinrich Boell Foundation - a German environmental NGO - and Friends of the Earth. The first English version for the international market was released on Thursday.

But the Meat Atlas is not necessarily meant to turn you veggie - although the cover title "facts and figures about the animals we eat" might appear blunt to the more squeamish.

The aim is to inform consumers about the dangers of increasingly industrialised meat production, says Barbara Unmuessig, the foundation's president, herself a self-confessed enjoyer of the occasional organic steak.

"In the rich North we already have high meat consumption. Now the poor South is catching up," she said. "Catering for this growing demand means industrialised farming methods: animals are pumped full of growth hormones. This has terrible consequences on how animals are treated and on the health of consumers."

In the United States more than 75kg (165lbs) of meat is consumed per person each year. In Germany that figure is around 60kg. Huge amounts compared to per capita meat consumption rates of 38kg in China, and less than 20kg in Africa.

But whereas in the developed world meat consumption has stabilised - or in some countries such as Germany, is even falling - in other parts of the world, particularly in India and China, consumers are taking enthusiastically to a meat-heavy Western diet.

There are social consequences, according to the Meat Atlas: the more meat we eat, the more animals we have to feed.

As a result increasing amounts of agricultural land are being given over to grow animal feed, such as soya. Globally 70% of arable land is now being used to grow food for animals, rather than food for people, says the Heinrich Boell Foundation.

This is undermining the fight against starvation and poverty, says Barbara Unmuessig, as individual farmers are pushed off their land by huge competitive corporations. And industrialised methods have led to an overuse of damaging chemicals, she believes.

Guilt-inducing

But Germans are torn.

On the one hand, this is a country with a powerful meat industry which slaughters 700 million animals a year - as well as a strong tradition of eating meat: wandering round chomping on a sausage is a normal part of most street festivals, and dried pieces of salami, wrapped in plastic wrappers like chocolate bars, are popular snacks.

German consumers are also used to the cheap food which is a direct result of industrial farming methods. The average German household spends around 10% of its entire income on food today, one of the lowest figures in the world, compared to more than 30% three decades ago.

At the same time, though, environmental concerns rank high in Germany. The Green Party is a powerful political force here, with 63 seats in the national parliament.

And saving the planet is not just a left-wing or fringe issue: it was a centre-right government, led by Angela Merkel's Christian Democrats, which decided to phase out nuclear power within the next decade because of fears of damaging the environment.

And culturally, German society has an almost fetishised love of all things deemed to be natural.

So eating meat has become a guilt-inducing balancing act for your average socially conscious, environmentally aware German consumer.

But attempts to force the issue have fallen flat. An initiative proposed by the Green Party before the recent election to introduce a weekly vegetarian day in work canteens was ridiculed by opponents as an unwarranted infringement of personal choice.

Steffen Hentrich from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, a free market think-tank, disagrees with the connection made by the Meat Atlas between meat-eating and environmental damage.

"We all want a cleaner environment. But meat-eating in itself is not the problem. It's rather the political frameworks in developing countries which cause the environmental damage. So we shouldn't have a bad conscience."

He says that meat-eating is being stigmatised in Germany, and that a lot of the statistics in the Meat Atlas are interpreted in a subjective political manner - criticising phrases like "in slaughterhouses the battle for the lowest prices is being fought on the workers' backs" as politically-biased anti-capitalist language.

And he believes that too often in Germany there is a romanticised idea of the traditional meat industry which ignores the reality of the past.

"A complete rejection of modern farming methods is just not legitimate," he argues. "I grew up near a sheep slaughter house. I saw how sheep were killed. And it wasn't kind or pretty. In the past the welfare of the animal was the bottom priority."

"Our aim is not to make anyone feel guilty," counters Barbara Unmuessig. "It's not about preaching or moralising to people. What we eat is a private matter. But it's important to remember that what we put on our plates has political consequences."

Eat less and eat better, appears to be the message for tortured environmentally conscious meat-eaters.

- Published17 December 2013

- Published16 March 2012

- Published30 June 2013

- Published8 April 2013

- Published4 March 2013