President Francois Hollande's ' affair' tests French privacy limits

- Published

President Francois Hollande has said the pictures are an invasion of his privacy

After the bombshell, the silence.

Perhaps the most noticeable thing about the presidential love scoop is the near absence of a reaction.

The main French television stations are treating the story with coy disinterest. For most of them it is way down the running order: a bit of muck dug up by their (distant) cousins in the "people" press.

Mid-morning, no-one had even sent a crew to film the alleged trysting-place. When I arrived, I was expecting hordes. But only I and a Belgian snapper were present.

Even on the French version of Google News, you have to look hard to find the latest on the Hollande-Gayet match.

Either there is genuinely no interest in the story; or there is a vast conspiracy to pretend no-one's interested.

From an Anglo-Saxon perspective, of course it looks faintly ludicrous - as if the French can't spot a good tale when it's staring them in the face; or else are too scared to tell it.

But from a French point of view it is different.

So much of the French way of doing things is conditioned by their horror at what they see when they look across the Channel. This nostrum certainly applies in the world of the press.

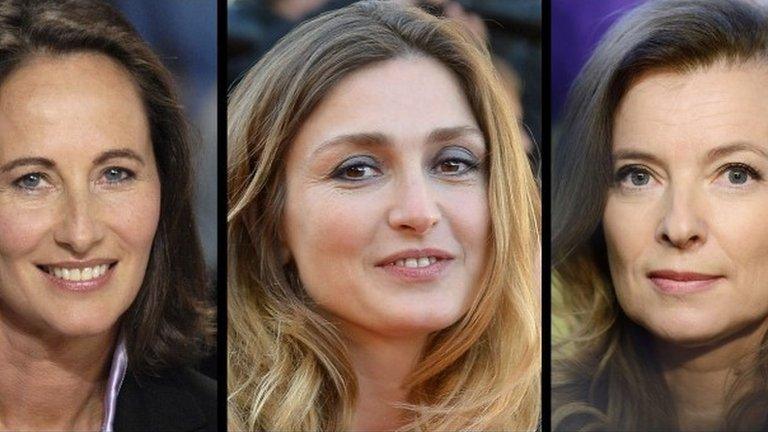

Mr Hollande - pictured here with partner Valerie Trierweiler - will now find it difficult to relaunch his presidency, as he had been planning to do this month

'People' watching

The French are brought up to believe in the appalling intrusiveness of the British and American tabloids. They also like to nurse the notion that - being open-minded types - they don't give a hoot about politicians' private lives.

All of which explains why - if you ask them - most French people will agree that the Hollande love match is a non-story which their newspapers are quite right to treat with disdain.

And yet.

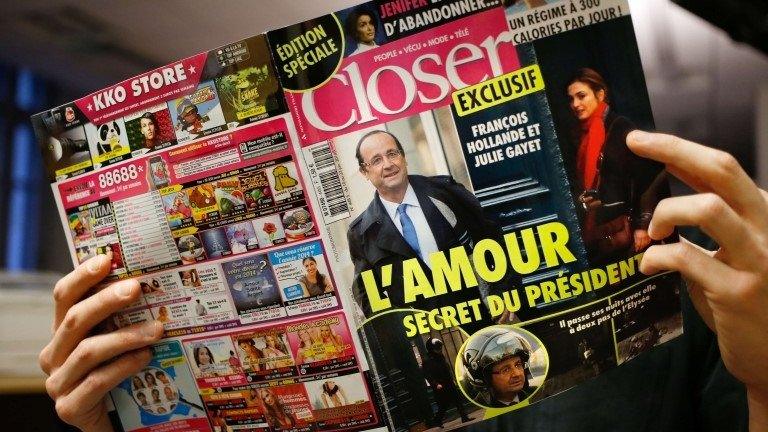

The very fact that Closer magazine has dared to go public with the story shows how things are moving.

President Francois Mitterrand's wife Danielle met her husband's secret daughter after his death

Such a report would have been unthinkable in the press a few years ago. True, the story of Francois Mitterrand's love-child with Anne Pingeot was first reported in Paris-Match. But that was almost certainly by prior arrangement with the people concerned.

The fact is that the limits of what constitutes privacy in France are being tested as never before. Technology is changing, the press is changing, and people's expectations are changing too.

Certainly French courts continue routinely to hand out damages to aggrieved celebrities.

But now judges are beginning to ask difficult questions about how far the celebrities have gone to entice media interest. By posing for money in the glossies, for example. And they adjust the damages accordingly.

And on the whole issue of public interest, a broader, more "Anglo-Saxon" reading is starting to make headway.

Only a few weeks ago, for example, publishers were given the go-ahead for a book disclosing the homosexuality of a leading member of the National Front. The judges said this was acceptable because it had a bearing in the debate on gay marriage.

Those in the know

In the Hollande-Gayet affair, there is at the very least a case to be made that disclosure is in the public interest.

Closer made a half-hearted nod in this direction by claiming there were security issues at stake. However given that the alleged love-apartment is in a guarded street next to the Elysee, that seems a little far-fetched.

Closer also printed topless photos of the Duchess of Cambridge in 2012

A more convincing case might be that Francois Hollande is the president of the French, and as such represents the French. So they have a right to know it, if he's planning to ditch his current "First Mistress" (Valerie Trierweiler) for another.

Or the French might like to know what lies behind the president's widely reported unhappiness at the moment. Is his unpopularity due to the dire state of the economy? Or is it his domestic situation?

But surely one of the strongest arguments in favour of disclosure is that, in fact, a lot of people had already heard rumours of the presidential affair.

It was just that, as usual, these people were the Paris "in-crowd" - the sort of people who gravitate around the same politico-journo-thespian circles that Hollande and Gayet both frequent.

Events of recent weeks - the rise of the new populism as represented by the comic Dieudonne - should have convinced anyone that one of the biggest problems in France is the growing divide between those inside the "system" and those out of it.

The long-standing complicity of insiders in keeping certain facts to themselves has certainly not helped.

- Published10 January 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published28 November 2014

- Published14 September 2012

- Published12 November 2013

- Published4 December 2013