President Hollande: Power and privacy in France

- Published

Valerie Trierweiler is First Lady, though not married to the president

This week we will learn much about the future of Francois Hollande's presidency. It is a decisive week. We may also learn much about the French press.

Tuesday was planned as the president's first press conference of the New Year and the occasion when he would try to relaunch his troubled presidency by outlining details of economic reforms.

Then his private life intervened. After a French magazine, Closer, on Friday revealed details of what it said was Francois Hollande's affair with the actress Julie Gayet, the Elysee Palace was quick to define this as a violation of the president's privacy. Most of the French press agreed.

The alleged affair scarcely made it on to the front pages. An instant poll revealed that 77% of the French people thought that the "love of the president" was a private matter that concerned only Francois Hollande. One senator probably summed up the view of most of the political class when he called it "voyeurisme intrusif".

But that line could not be held. There were a stream of unanswered questions: was there a security risk in the president of France moving around Paris on the back of a scooter? Was he vulnerable to attack or kidnap? When he remained at the apartment overnight did bodyguards stay with him? Who owned the apartment and were they trustworthy? What if news of the apartment had leaked to enemies of France or of the president? Were these risks that the president should have taken? Were public officials persuaded to cover up for the president?

All of these are questions that could be legitimately asked.

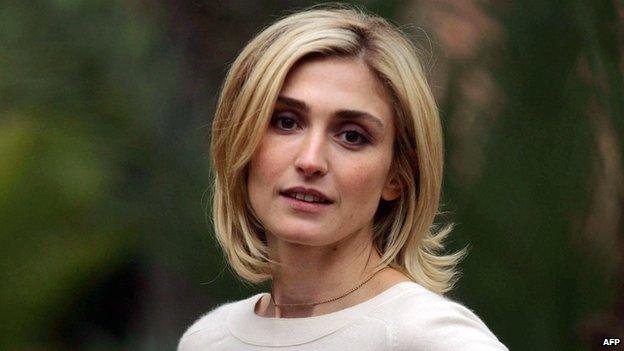

Julie Gayet, 41, has acted in several French films

Danger of ridicule

And then there are the more political questions: has the image of the president, under his black helmet on the back of a scooter, undermined the prestige and dignity of his office? Has he invited that most dangerous of sentiments for an elected politician - ridicule?

Whether France's press would pursue these questions remained unclear. Certainly there is a deep commitment to protecting the privacy of elected officials.

But then the socialist president's long-term partner Valerie Trierweiler checked herself into a hospital. Her staff said she was suffering from "a severe case of the blues". In an instant this increased the pressure on the president.

Even though they were not married she travelled as if she was France's first lady. Her spokesman Patrice Biancone said she had learned of the alleged affair from a magazine and had experienced "a big emotional shock".

Doctors have recommended that the former Paris Match journalist needs rest.

And so another set of questions arises: where does that leave the First Lady and do the French people have a right to know? Valerie Trierweiler has an office in the Elysee Palace with six staff - which is popularly known as "Madame's domain" - which is supported by public money.

Very few French politicians have dared step into this minefield, although Jean-Francois Cope, head of the opposition centre-right Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), said it was "disastrous" for the president's image. One columnist warned that when he tried to talk about his economic reforms he would be "inaudible".

The question for the Elysee is whether the president can successfully conduct a news conference tomorrow without awkward questions being asked about his personal life. Even if French journalists shied away from such questions almost certainly they would be asked.

And yet the future of his presidency depends on the economy. It remains sluggish. In his New Year's message the president said the state was "too heavy, too slow, too costly". So how does he intend to reduce the size of the state? There were hints of lower taxes for all.

Economic pressures

Having put up taxes in order to reduce the deficit, will he now reduce spending, and if so how? He promised businesses "a responsibility pact", whereby in exchange for taking on more staff taxes could be lowered. What are the details for such a reform? He spoke of "abuses" in the welfare system, but which ones will be singled out for reform? When he speaks of doing more while spending less, what does he have in mind?

His presidency hangs on the answers.

Will Francois Hollande, like his mentor Francois Mitterrand, reinvent himself as less a socialist and more a social democrat? Will a new, more market-orientated president emerge? Can he cast off the judgement that he is presiding over the "sick man of Europe"?

The risk is that, at some stage, the markets might insist on higher interest rates for buying French debt.

Credibility is the key and the president's personal life has become bound up with that.

- Published13 January 2014