Vatican faces test of attitude to abuse

- Published

The Vatican has refused to provide some of the information requested by the UN panel

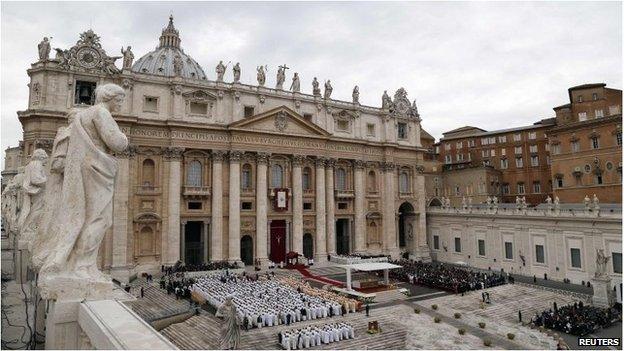

For the first time on an international public stage, a senior Vatican official will be asked to explain the Roman Catholic Church's handling of child sex abuse.

The momentous occasion will be closely watched by those who want the Vatican to address not just cases of abuse by priests, but suggestions that there were systematic efforts to cover them up.

Thursday's hearing, before the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child in Geneva, Switzerland, will also give an indication of how far the Vatican is prepared to go to co-operate with a major external inquiry into its conduct.

As a signatory of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, although not a member of the UN, the Vatican is required, at regular intervals, to provide the committee with information on how it is respecting children's rights, and to answer questions about concerns.

The announcement by the Vatican in December that it would not be sharing the results of its own internal inquiry into sex abuse with the UN committee has angered many; one group campaigning for the rights of victims called it "shameless and unacceptable".

The committee was bluntly informed by the Vatican that "it is not the practice of the Holy See to disclose information on the religious discipline of members of the clergy or religious according to canon law".

This was, the Vatican said, "to protect the witnesses, the accused and the integrity of the Church process."

Duty to protect

The chair of the committee, Kirsten Sandberg, said the Vatican, like all signatories to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, would be closely questioned at the hearing.

"We discuss all the issues under the convention," she explained. "So of course that dialogue in itself is a way of making the state conscious of what we think are the concerns."

Significantly, one of the convention's key elements is a child's right to protection from violence and sexual abuse.

Given the widespread allegations, and indeed documented cases, of abuse by Catholic clergy in church-run schools and institutions, the Vatican's responsibility to protect is sure to be raised by the committee.

Furthermore, Ms Sandberg explains, the UN committee will consider not only a report submitted by the Vatican on its compliance with the convention, but also 'shadow reports': information from other groups, including those representing victims.

Charles Scicluna, the Vatican's chief sex crimes investigator, will be taking the questions

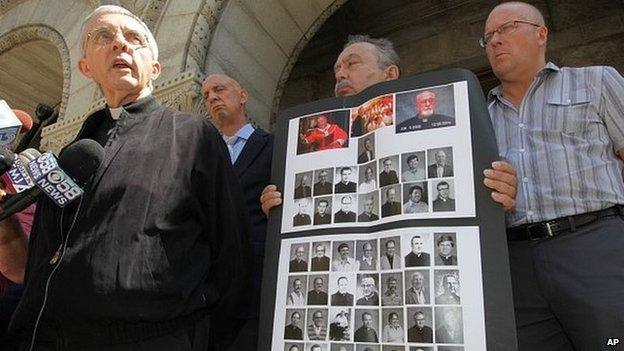

One of those groups is the Survivors Network for those Abused by Priests, or Snap. The group, supported by the US Center for Constitutional Rights, has submitted a 23-page report to the UN committee, detailing what it says is "the failure of the Holy See to uphold core principles enshrined in the Convention on the Rights of the Child".

Pam Spees, a lawyer with the centre, views the UN committee hearings as a promising sign "that this is part of a larger shift to bring more accountability and transparency to what has been an extremely non-transparent organisation".

Members of Snap have also travelled to Geneva. Among them is Miguel Hurtado, himself a victim of abuse as a child. For him, the hearings in Geneva are very important.

"I think it brings the message that sexual abuse, by a priest, is a human rights violation," he said.

"No institution, however powerful, has the right to police itself… this is a human rights violation, a crime, and it should be dealt with accordingly."

No enforcement

But, like many arms of the United Nations, the committee on the rights of the child has no power to enforce, even if it is aware that serious abuse is taking place.

Instead, the committee operates on a recommendation basis: where it has concerns, or feels that change is needed, it offers advice.

Campaigners for abuse victims have been demanding greater accountability from the Vatican

While this may sound like a rather ineffective way of doing things, Kirsten Sandberg points out that many countries have implemented committee recommendations, from ensuring all children are registered at birth (crucial in later life to ensure a place in school, or access to health care), to focussing on the rights of girls to education, to raising the age of criminal responsibility, and introducing child friendly courts and legal services.

She also believes that the UN committee hearings, which are public, and are webcast, are a powerful spotlight on countries which neglect children's rights, in particular if they fail to act on the committee's advice.

"If time after time they come back and haven't done what we've told them of course it will give a bad impression with the public," she explains. "I think that has an effect."

Pam Spees agrees, pointing out that now that the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child has summoned the Vatican, other UN committees are taking a closer look too. On the grounds that rape and sexual violence constitute cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, the Vatican has been asked to appear before the UN Committee on Torture later this year.

"Up to now the Vatican hasn't had to answer to an international body in a formal setting'" she said.

"So the fact that this issue is being taken seriously is momentous."

- Published5 December 2013

- Published3 December 2013

- Published24 August 2013

- Published5 April 2013