Hollande-Trierweiler split: A bachelor in the Elysee

- Published

Well, that's one experiment I will not be doing again in a hurry.

Such, presumably, is the feeling of French President Francois Hollande as he looks back at the end of 20 months in the Elysee presidential palace with his now ex-partner Valerie Trierweiler.

His instincts told him it would be problematic - having a strong-willed, independent-minded, unmarried professional journalist sharing his presidential home. And his instincts were right.

Now, following this painfully public separation, his instincts have another piece of advice: this time, stay single.

And so, in January 2014, there commences in France one of those rare periods when the head of state is unaccompanied by an official consort.

The boffins have been through the annals to reveal that there have only ever been three bachelors in the presidency.

The first was Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (the original Napoleon's nephew), a notorious philanderer who was single when he became president of the Second Republic in 1848. (He married later, after he became emperor.)

The second was the now-forgotten Gaston Doumergue, who served from 1924 to 1931 and finally married his long-standing mistress 12 days before leaving office.

And the third was Mr Hollande's predecessor and rival, Nicolas Sarkozy, who had a brief lonely period at the Elysee between his two wives Cecilia and Carla.

Otherwise, French leaders have always been married. Over the decades - especially in today's Fifth Republic with its quasi-monarchical institutions - having a first lady has somehow become part of the presidential package.

But of course there is nothing in the constitution that mentions a first lady: it has all been purely ad hoc. And so now the absence of a consort should change little beyond the protocol.

"Being single in the presidency won't affect the dignity of the office. Not in a mature democracy," says Jean Garrigues, professor of contemporary history.

"No, what's far more damaging is claiming to be a 'normal' president, behaving like any ordinary man in the street, and getting caught on a scooter coming back from one's mistress."

Marriage protection?

One aspect of the affair that has been much remarked on is whether it would have made a difference if Mr Hollande and Ms Trierweiler had actually been married.

Marriage, the argument goes, would have given Ms Trierweiler a more secure footing in the Elysee. Marital infidelities would have been seen as just that - something to be regretted and contained, but not necessarily the first step to eviction.

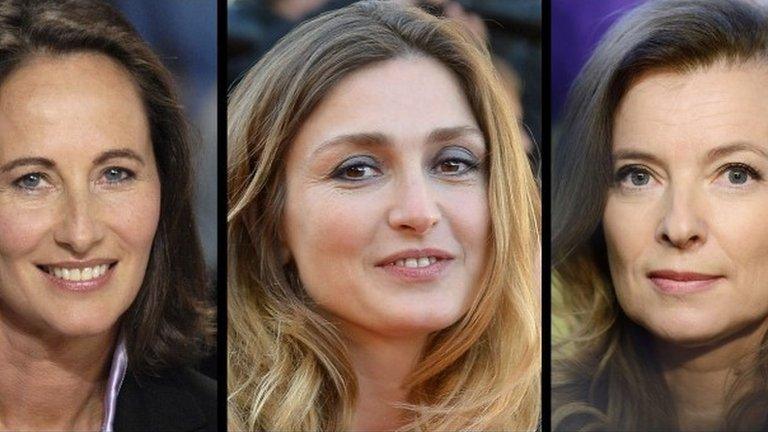

Valerie Trierweiler struggled in the popularity stakes

By choosing to be modern libertarians - refusing to be encumbered by the bonds of wedlock - the couple exposed themselves to the remorseless logic of romanticism: once love has gone, why bother?

Once Mr Hollande began to get irritated by his partner's evident lack of aptitude for her role, the path was laid to dissolution. There was nothing in the way to stop it.

Which leads to the question of the president's own behaviour.

It is fair to say that Valerie Trierweiler was never a popular figure.

There is a famous video of Francois Hollande, on a walkabout in provincial France, being approached by a middle-aged lady who says: "Don't marry her, Mr President! We don't like her!"

But the distressing saga of the last two weeks has awakened a sympathy for the former first lady.

From hard-headed conniver, her image has changed to one of victim.

No-one can doubt the depth of her suffering - especially after all she invested in helping Mr Hollande to the helm of state.

Less of a leader?

Meanwhile, the president, many would argue, comes out looking diminished.

Leaving aside the mockery occasioned by the original pictures in Closer magazine, the president then spent more than two weeks dithering, before finally dismissing Ms Trierweiler in a blunt - and some would say heartless - 18-word communique.

The statement, which he personally read out over the phone to the political editor of the AFP news agency, is entirely in the first person singular. It is I, Hollande, bringing to an end my shared life with Valerie Trierweiler.

President Hollande is already deeply unpopular

In no sense is it a statement of a joint arrangement, by the couple. It is an assertion of Mr Hollande's personal authority, at a time when he knows it has been called into question.

But having to assert authority is in itself often an admission of its lack.

According to Anna Cabana, a biographer of Ms Trierweiler, many women will see the president's behaviour as distinctly "inelegant".

It is an oft-repeated nostrum that the French keep separate in their minds the private and the public, and will not be swayed in their judgement of the president by considerations of his infidelity.

In fact it is more complicated than that. The events of the last two weeks have been followed by every sentient being in the land, and they cannot help but filter through into perceptions of their leader.

If he were a much-loved president, it would matter less. But he is already deeply unpopular.

In this affair, he has been variously ridiculous, undignified, irresolute and inelegant. That cannot help.

So who can blame him for wanting an uncomplicated private life?

If actress Julie Gayet has plans for the Elysee, she would be advised to keep them on hold.

A second first partner - or should that be a first second partner? - there will not be.

- Published25 January 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published2 April 2014

- Published14 January 2014