Abortion bill finds Spain a changed country

- Published

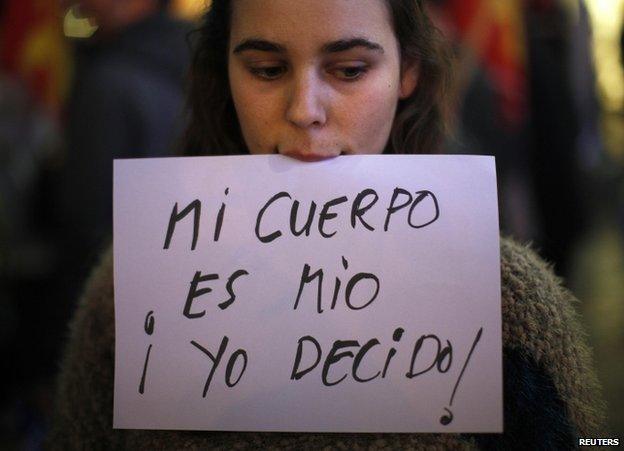

This woman at a recent pro-choice protest in Malaga held a sign which read "My body is mine. I decide!"

Thousands of demonstrators marched on the Spanish parliament on Saturday in protest at a draft law that would ban abortion except in cases of rape and when the mother's health is at serious risk.

The proposal has provoked some dissent within the ruling Popular Party and recent polls suggest the measure is likely to lose the party votes. So why has the issue returned to the centre of Spanish politics?

For many people living, or holidaying, in one of Spain's big cities, this country feels as liberally minded as any other in Europe.

However, scratch below the surface and there is another, more conservative, Spain, steeped in tradition and, often, in the Roman Catholic Church.

It is why the issue of abortion has resurfaced on to the political agenda, with the government proposing the toughest restrictions since abortion was legalised in 1985.

Some in Spain are uncomfortable with the social change that has come in the four decades since the death of the dictator Francisco Franco.

'Changed country'

Fernando Gotazar, from the pro-life organisation the Spanish Family Forum, believes that public opinion is turning against the current abortion law, passed by the previous Socialist government in 2010, which allows any woman to have an abortion within the first 14 weeks of her pregnancy.

"The main point is not to punish those causing abortion, it's to make a social climate in favour of life," he says.

He accepts that a high proportion of people in Spain who are against abortion are religious, but says there are also many who are not.

"The debate is not centred on religion," he insists.

The government's bill would also not allow women to abort in cases of serious foetal abnormalities.

Professor Ines Alberdi, a sociologist at Madrid's Complutense University, believes most people are opposed to the proposed restrictions: "Little by little, they have come to accept social change in areas like divorce, gay marriage and a woman's right to terminate an unwanted pregnancy."

She describes Spain as Catholic but only "culturally speaking".

"People like the rituals and tradition but at the same time they don't bother to follow the doctrine," she proposes.

Of those who want to return to prohibition, she says: "They are a minority, but they can't accept that the Church is no longer the moral authority in Spain."

'Pressure to abort'

Ines Cuartero now has two healthy young children.

Ines Cuartero's son, Juan Pablo, died aged 15 months (family photo)

However, when she was pregnant for the first time, she was told her unborn baby had a problem with his heart and would be born disabled.

"It's tough because, as a parent, you feel that some people believe that in some way the child that you love is worth less," she says.

Juan Pablo died aged just 15 months. But Ines never considered having an abortion.

She believes Spain's abortion law needs changing so that people in her position do not feel under pressure to abort.

"When you find yourself in that situation you feel defenceless." she says. "The doctors give you the option of aborting but they should also say to you that if you don't want to have an abortion, they will support you."

One woman tells the BBC her abortion would not have been allowed under the new legislation

'We cried a lot'

But "Laura", who did not want to give her real name when we met recently in Barcelona, faced her own moral dilemma when, to her surprise, she realised she was pregnant.

She and her partner had been taking precautions, as they already had two children, and they did not plan to have another.

"It was one of hardest things I've ever done," she says. "You have to decide to end a life."

She and her partner wanted to dedicate more time to their two young children, and so they decided that an abortion was the right thing to do.

"We cried a lot," she says. "It's not a decision you take easily. A doctor or a politician should not decide whether I will have a kid or not."

The pro-choice lobby, which has come out fighting since December when the draft law was published, believes the debate is a question of a woman's right to decide.

"I was born with rights which people fought for and won, so it's hard for me to think we're going backwards," says Nathalie Manero, 25, from the action group Deciding Makes Us Free.

Government figures show that the number of abortions has fallen in Spain since the 2010 law took effect.

"You reduce the number of abortions through good sex education and good contraceptive methods, not because of a more restrictive law," Ms Manero says.

Cross-party concern

Unlike the UK, Spain is not accustomed to politicians speaking out publicly against a policy of their own party.

However senior members of the Popular Party have openly criticised the proposed new law.

The party's chief in the southern region of Extremadura, Jose Antonio Monago, has said that "no-one can deny the right of a woman to become a mother, nor can they oblige her to become one".

The Popular Party committed itself to changing the law on abortion in their 2011 manifesto but it took the government two years to publish a draft law.

And it will probably be months until we know whether that law will be modified and, if so, by how much.

In many ways, the evolution of Spain's abortion law, and the ensuing debate on the issue, reflects the persistent struggle in a post-Franco, democratic Spain, between those who have embraced social change and those for whom the change has come too fast, or too far.

- Published20 December 2013

- Published21 August 2023