European economy: How French and German states compare

- Published

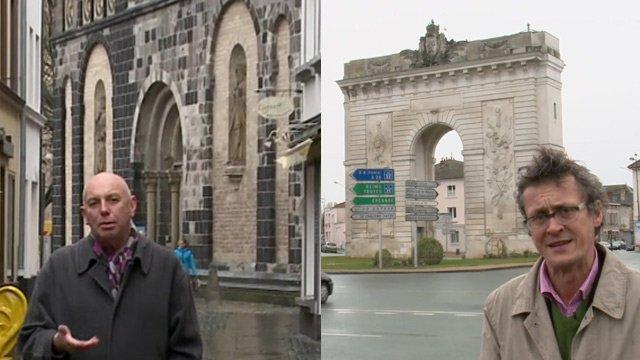

Hugh Schofield reports from Chalons-en-Champagne in France, and Stephen Evans reports from its German twin-town, Neuss

France has revealed that its sluggish economy grew by 0.3% in the last three months of 2013. With debt and deficit levels high, the government has begun taking steps to reduce the country's burgeoning public sector.

In France, if you want to run away to join a circus, the state can help.

Simply apply to the National Centre for Circus Arts (CNAC), which since 1985 has been based in the eastern town of Chalons-en-Champagne.

Every year around 20 undergraduates start the course, learning to become trapeze artists, acrobats and rope-dancers. All without charge.

Why - some might wonder - is the state using taxpayers' money to subsidise young people in tights?

Plenty of circus schools exist around the world, but in the vast majority of cases they are private. Students pay fees, or get sponsorships. But not at the CNAC.

The answer, according to the school's director Gerard Fasoli, is that "here in France, we regard the circus as part of culture, so it is perfectly normal that we use public money to train the next generation".

It is a perfect glimpse at how France is different. What in most other countries would be regarded as an extravagance - especially in these straitened times - is held up as a mark of pride.

According to Mr Fasoli, while there are certainly ongoing discussions about how to make savings, the culture ministry has no intention of cutting off the money. State-funded tightrope-walking is safe.

State spending is seen as a springboard for success by many in France

But with the French economy stalling, the mood in government is shifting

Administrative layer cake

Circuses aside, the state figures prominently in Chalons.

Historically the town has always been an administrative centre. But today the multiplication of tiers of government has made it a bureaucratic hive.

A walk down the main street makes the point. At one end is the headquarters (in a former Roman Catholic seminary) of the regional government of Champagne-Ardennes.

Walking beneath the monumental Porte Sainte-Croix, you pass the headquarters of the department (or county) of the Marne; then the departmental archive; then the prefecture, representing the national government. Finally - after a quick detour for the law courts and the army barracks - you come to the Hotel-de-Ville, where the municipality is based.

It is a perfect glimpse at the "millefeuille" of French government - so called after the multi-layered patisserie.

Chalons may display an unusual concentration of different types of "fonctionnaires" (civil servants), but it remains the case that across the country nearly one in four of the workforce is still employed by the state.

Ask most French people and they would probably say there is nothing intrinsically wrong in that. A big state has always been part of society.

But today even the Socialist government admits that the public sector needs to be reduced. They say it is an essential part of the task of restoring order to government accounts - without which debt and deficit levels will reach unsustainable levels.

France's problem is two-fold: first, finding the courage to wield the axe; and second, instilling a spirit of free enterprise to take over in those areas where the state has been excised.

Gradually across France attitudes to business creation are changing. Younger generations are more aware of changes happening in the rest of the world.

One layer of the thousand-leaved "millefeuille" of the French state

Painful change

But for many it is all too late.

"My children are grown up and they have all gone to pursue their careers abroad - in Asia," says Elisabeth Michel who with her chef husband Jacky runs the wonderful Hotel d'Angleterre in the town centre.

"There are so few opportunities here in France for young people who have ideas and want to make a mark. Life is made so hard, I tell you. In France there is a lot of questioning going on at the moment."

At the TI Automotive car parts factory, the town's biggest private employer, European Managing Director Oliver Schmeer - a German - takes a similar view.

He recognises that the Socialist government has changed its rhetoric, and now talks up the role of business in creating jobs. Last month President Hollande promised to cut social charges for companies, if they in turn promised to employ more workers.

But Mr Schmeer says that France, with its ultra-complex labour code, high taxes and militant trade unions, is stuck way below its economic potential.

"A lot of people in government still don't understand industry. They don't understand that we rely on customers to place orders, otherwise we have no jobs to offer. We can't offer jobs to people to build things that no-one wants," he says.

Chalons is not a rich town. Around two-thirds of adults do not even pay income tax, which shows that most are at the bottom end of the pay scale. Many shops are closed, driven out of business by out-of-town superstores. At night the town is dead.

At the job centre, they say that unemployment is around 10.6% - more or less in line with the (near-record) national average.

Unemployment benefit kicks in if you have been at least six months in a job and are made redundant. Normally you can expect a monthly pay-off worth around 70% of your former income, for up to two years. Though of course many job-seekers do not qualify for this and just get the basic dole.

There have been calls to change the system, to make it less generous: cutting costs and less automatic, so job seekers cannot turn down successive offers.

But with joblessness so high in France, there is little political capital to be gained from "bashing" the unemployed, as it is likely be portrayed.

Along with a big state, generous welfare is central to France's social contract. But the question is whether either can be sustained at current levels, without dragging the economy down.

Bread and circuses. It all costs money.

- Published12 February 2014

- Published14 January 2014

- Published14 January 2014

- Published9 January 2024