Why Crimea is so dangerous

- Published

The peninsula of Crimea in southern Ukraine is at the centre of what is being seen as the biggest crisis between Russia and the West since the Cold War.

Troops loyal to Russia have taken control of the region and the pro-Russian parliament has voted to join the Russian Federation, to be confirmed in a referendum.

Why has Crimea become a flashpoint?

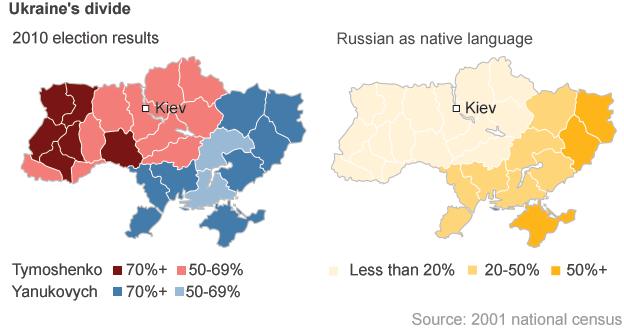

Crimea is a centre of pro-Russian sentiment, which can spill into separatism. The region - a peninsula on Ukraine's Black Sea coast - has 2.3 million people, a majority of whom identify themselves as ethnic Russians and speak Russian.

The region voted heavily for Viktor Yanukovych in the 2010 presidential election, and many people there believe he is the victim of a coup - prompting separatists in Crimea's parliament to vote for joining the Russian Federation and a referendum on secession.

Is Crimea truly Ukrainian?

Watch a short history of the Republic of Crimea

Russia has been the dominant power in Crimea for most of the past 200 years, since it annexed the region in 1783. But it was transferred by Moscow to Ukraine - then part of the Soviet Union - in 1954. Some ethnic Russians see that as a historical wrong.

However, another significant minority, the Muslim Crimean Tatars, point out that they were once the majority in Crimea, and were deported in large numbers by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in 1944 for alleged collaboration with Nazi invaders in World War Two.

Ethnic Ukrainians made up 24% of the population in Crimea according to the 2001 census, compared with 58% Russians and 12% Tatars.

Tatars have been returning since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 - causing persistent tensions with Russians over land rights.

Will Crimea break away?

It appears to be heading that way with a referendum due on 16 March.

The region remains legally part of Ukraine - a status that Russia backed when pledging to uphold the territorial integrity of Ukraine in a memorandum signed in 1994, also signed by the US, UK and France.

Crimea is an autonomous republic within Ukraine, electing its own parliament, with a prime minister appointed with approval from Kiev. But now Crimean MPs have appointed a pro-Moscow leader, Sergei Aksyonov, who wants Crimea to unite with Russia, and has called the referendum.

What will the referendum decide?

A billboard sets out the choices for the vote: Crimea with a swastika, or Crimea in Russia

Voters will be asked two questions?

Are you in favour of re-uniting Crimea with Russia as a constituent part of the Russian Federation?

Are you in favour of restoring the Constitution of the (autonomous) Republic of Crimea of 1992 and retaining the status of Crimea as part of Ukraine?

Under Ukraine's constitution, external, "issues of altering the territory of Ukraine are resolved exclusively by an All-Ukrainian referendum". Equally, Crimea is entitled to call what are termed local referendums, external.

There seems little doubt of a Yes vote. Kiev has dismissed the referendum as illegal, but is hardly in a position to stop it going forward. And the West says it will not recognise the result.

What's Russia's position?

Russia's lease on the Sevastopol base lasts until 2042

Thousands of pro-Russian troops are in control of Crimea. Moscow denies they are Russian soldiers, calling them Crimean "self-defence" forces - though correspondents say they are too well-trained and equipped to be an irregular militia.

President Vladimir Putin has defended Crimea's decision to stage the referendum as "based on international law".

Russia has a major naval base in Sevastopol, where its Black Sea fleet is based. Under the terms of the lease, any movement of Russian troops outside the base must be authorised by the Ukrainian government.

There have been reports of Russian envoys distributing Russian passports in the peninsula. Russia's defence laws allow military action overseas to "protect Russian citizens".

Could the Crimean crisis spark a war?

Mr Putin has obtained parliamentary approval for troop deployments not just in Crimea, but Ukraine as a whole. Moscow, which regards the new authorities in Kiev as fascists, could send troops to "protect" ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine. That would enrage nationalists in western Ukraine, who hold positions in the new government.

Western powers have strongly condemned the Crimea takeover. Nato is unlikely to react militarily, but has sent extra fighter planes to Poland and Lithuania and is conducting exercises.

The US and EU are considering sanctions, but President Putin may believe that they will not last - as was the case after the Georgian war of 2008. Then, Georgian forces were routed by the Russian military when trying to retake the Georgian breakaway territory of South Ossetia. Russian forces are still in control, and Moscow has recognised both South Ossetia and a second Georgian region, Abkhazia, as independent.

Wasn't there once a war in Crimea?

Crimea has been fought over - and changed hands - many times in its history.

The occasion many will have heard of is the Crimean War of 1853-1856, known in Britain for the Siege of Sevastopol, the Charge of the Light Brigade, and the nursing contributions made by Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole.

The war was a result of rival imperial ambitions, when Britain and France, suspicious of Russian ambitions in the Balkans as the Ottoman Empire declined, sent troops to Crimea to peg them back. Russia lost.