Bayern Munich's Uli Hoeness: Mr Football in the dock

- Published

Uli Hoeness was first a striker for Bayern Munich, then its manager and is now its president

He is Germany's Mr Football. Not only was Uli Hoeness a star on the field but a great mover and shaker off it.

As president of Bayern Munich, one of the world's greatest clubs, he was the man with whom everybody from Chancellor Angela Merkel down was pleased to be seen.

In a court room in Munich on Monday, the allure and the glamour seemed a long way away.

He is accused of not declaring 33,526,614 euros (£28m; $46.5m) in income, on which he should have paid 3,545,939 euros and 70 cents.

His lawyer has now said that this figure of unpaid tax is actually higher - about 18.5m euros.

Mr Hoeness came forward to admit the account's existence only after the media got wind of it. He received a phone call warning him of the investigation when he was having lunch with Chancellor Angela Merkel, a measure of the exalted circles in which he moved.

In court, he stood in the darkest of suits; smiling politely - and perhaps nervously - to the lawyers in their robes around him.

At 62, he is portly, perhaps twice the weight he was when in 1974, as a magical forward, he helped Bayern Munich win the European Cup and Germany the World Cup.

But before the judge he still keeps his shoulders back and looks people in the eye.

Uli Hoeness's story is true rags to riches.

He was the son of a butcher who then expanded the family business into large-scale sausage-making. His skill with money made him more money, but his skill with his feet made him famous.

After he had hung up his Bayern boots, he became the club's general manager and then president, a position he still holds. He turned the club he played for into one of the world's greatest sporting institutions.

But he has tripped up over his financial affairs. He does not dispute that he had a bank account in Switzerland in which he had deposited millions of euros without informing the German tax authorities.

The prosecution says the Bayern president should get seven years behind bars.

An added difficulty for the football star is that the judge in this case, Rupert Heindl - dubbed "judge merciless" by the German press for jailing a pensioner - is thought not to like deals whereby transgressors avoid jail by repaying what they have gained illegally.

Uli Hoeness is still popular among Bayern fans who credit him with building up the club

The trial is seen by German media as one of the most spectacular of the year

His original intention to admit guilt privately and repay tax came unstuck when the existence of the secret account emerged in the press. Before that revelation, Hoeness may have hoped to make good the financial damage and move on, with his reputation intact, but then the publicity made that impossible.

His reputation is damaged but it is far from destroyed.

He remains a popular figure. Fans of Bayern Munich invariably voice their condemnation of the secret account but usually go on to say how much they still like him and how much he has done for their club.

When he offered his resignation as Bayern president, the fans at the meeting chanted his name and he wept: a grown man with a giant reputation for crying copiously, the apparent penitent bowing for forgiveness before his followers.

The judge is not likely to be so generous. Nor are the German tax authorities. They have been determined and clever in their pursuit of the rich who fail to pay their dues.

Investigators are making use of CDs full of information about accounts of rich Germans with Swiss banks, much to the anger of the Swiss authorities.

The German authorities accept that the information they bought may have been illegally obtained by the seller, but the argument is that this is a small crime compared with that of the collective fraud against the public by failing to pay millions - perhaps billions - of euros in tax which is needed for schools, hospitals and other public services.

The second strand of their tactic is to promise an amnesty for those who come forward.

Uli Hoeness (R), here with Bayern chairman Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, remains popular with fans

They pay the back tax plus interest but escape jail.

But the fly in the ointment for those fearing they are about to be fingered is that the amnesty does not apply if the investigation was already under way - hence Uli Hoeness's difficulty.

And the former football star is not alone.

There has been a string of revelations of unlikely people with secret Swiss bank accounts.

The German press has been dwelling on the revelation of the accounts of a prominent left-of-centre politician, of the editor of one of the country's most august newspapers and of one of the country's most vocal feminist activists.

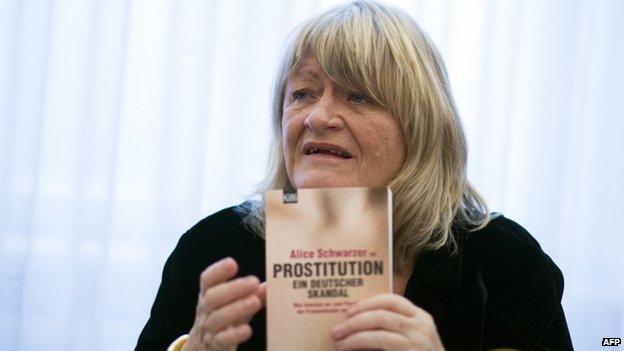

Alice Schwarzer is a big television personality who tours the country's studios and halls, opining to big audiences about everything from prostitution to Roman Polanski.

She said on her website: "The motive for everything I do is justice. A life in which I hadn't done everything I could to implement this ideal would have been a wasted life."

Then it was revealed that since the 1980s she had also had a secret Swiss bank account, unbeknownst to the German tax authorities. After it was revealed, she issued a statement: "Yes, I had a bank account in Switzerland. I regret it with all my heart."

Feminist journalist Alice Schwarzer has criticised Germany's prostitution laws saying it is "a paradise for pimps"

She has now paid back 10 years of tax plus interest (though it is not clear if she is exempt from paying tax from further back because of a legal statute of limitations). And she has escaped jail.

Ms Schwarzer blames the trouble she's now in partly on the media which she thinks came after her unfairly because of her strong stand on women's rights.

She remains defiant: "Yes, I have made a mistake. I was careless but I've made good the error. I have settled about €200,000 in taxes plus interest on arrears".

The case, she says, has been settled so she asks incredulously for what reason she continues to face denunciation.

Uli Hoeness, however, is making no such claims of defiance. He does not see himself as deeply wronged.

- Published24 April 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published26 May 2013