Ukraine crisis: Is this Cold War Two?

- Published

We overdo the talk of turning points and milestones in covering summits, but, when it comes to the G7 at The Hague, it's very hard to see it in any other terms.

Events in Ukraine have profoundly changed Western perceptions towards Russia and it's very hard to envisage any rapid return to business as usual.

Arriving in the Netherlands for this summit, President Barack Obama said the US and Europe were united in imposing sanctions that would bring "significant consequences to the Russian economy".

Michael McFaul, the former US ambassador in Moscow, wrote on Monday morning that President Putin "embraces confrontation with the West… [and] has made a strategic pivot".

A Ukrainian soldier stands guard near a tank position close to the Russian border

Carl Bildt, Sweden's foreign minister, added on Twitter that Mr McFaul's gloomy prognosis was understating the problem since the Russian president was "building on deeply conservative orthodox ideas"., external

When the people responsible for good East-West relations are saying this, you know that this is no flash in the pan.

So is this Cold War Two or a lesser realignment in world politics?

Much depends on Russian actions during the coming days: an invasion of eastern Ukraine would likely trigger a full-scale trade war, but consolidation of the hold on Crimea, with continued covert support to militant Russian groups in Donetsk or Kharkiv, would pose a trickier dilemma to Western policymakers.

Climate of tension

However, since the Kremlin is not only unlikely to reverse its stance in Crimea but is also now brandishing the possibility of intervention in support of Russians in Moldova or the Baltic republics (members of Nato after all), it is evident that the new climate of tension is not going to be soothed rapidly and may get far worse.

Up to now the public perception of European dependence on Russian trade has led many to assume that meaningful sanctions or a real realignment are unlikely.

But those who hold that view may be under-estimating the degree to which European leaders are already agreeing (so far in private) to harsher measures and the extent to which they feel guilty at not having acted more effectively years ago.

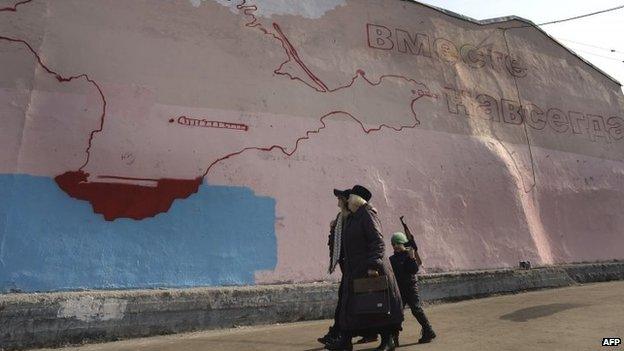

A mural in Moscow depicts the Crimea peninsula and declares "Together Forever"

The "targeted measures" enacted so far by the US and EU simply penalise some of Mr Putin's friends and political allies. The Level 3 sanctions already agreed in principle by EU leaders last week target certain Russian enterprises and would take us into genuine trade war territory.

Last week also, the European Commission pledged to step up work to reduce energy dependence on Russia. And it is in this area that European leaders have shown their resentment at having been taken in by Mr Putin before and allowed things to return to normal.

The interruption of Russian gas supplies in 2006 and the 2008 war with Georgia were events that prompted previous pledges to lessen energy dependence.

But back then many privately blamed Georgia for provoking the Russian military and couldn't wait to get back into business with a booming BRIC economy.

Merkel's stance

There is a seriousness now about reducing Russian gas imports further, buttressing Ukraine's ability to do the same, and agreeing further measures in advance of the next Russian move, not after it.

As the Swedish prime minister told Newsnight earlier this month, a trade war will hurt Russia more than it will hurt the EU.

Russia accounts for 7% of European exports, but those coming the other way represent 21% of Russia's trade.

Nobody personifies this sense of wanting to avoid getting taken in again by the Kremlin more than Germany's Chancellor, Angela Merkel. While it is true that German trade remains highly significant in her calculations, her political stance has become noticeably harsher in recent days.

How far all this will go, even without further Russian military action against Ukraine or Moldova, remains unclear.

The G7 talks are on the sidelines of a long-planned summit on nuclear threats

If the EU's project to reduce its dependence on Russian energy bears fruit, it is possible that the recent growth in trade across the old iron curtain will be reversed.

Other debates will take place among the G7 leaders, in the corridors of the Berlaymont, headquarters of the European Commission, and at Nato: to what extent are previously planned diplomatic engagements with Mr Putin now toxic? How can partnership with Ukraine be strengthened? And does the long slide in European defence spending need to be checked?

Some of these answers are becoming clearer. There will be no G8 summit in Sochi, there could be further steps against President Putin's inner circle, and increased deployments of Nato forces to the Baltic republic will be maintained.

But many uncertainties remain, including, at the most dramatic level, whether further Russian military action might lead to large-scale sanctions, US troop cuts in Europe being reversed, and a new diplomatic ice age.