Bosnia's wartime rape survivors losing hope of justice

- Published

Lejla and Zihnija, who survived rape in the Bosnian war, told BBC News about their experiences.

The Bosna, the river that gave this country its name, flows northwards through the city of Zenica, slicing it in two. On its banks, the chimney stacks of the giant steelworks in the centre of the city funnel thick smoke into the surrounding valley.

In the garden of a women's refuge overlooking the plant, Lejla describes the brutality she suffered as a teenager.

"I was 14 and living with my grandmother when the war began," she says.

"I was captured and spent three years in a prison camp, where we were forced to do manual labour. Later, I was separated from the rest of the prisoners along with three other women and taken to a house.

"The soldiers would drink. We would have to serve them like slaves and they would rape us."

Estimates for the number of women like Lejla who were subjected to sexual violence during the Bosnian War range from 20,000 to more than 50,000.

The true figure will never be known, not least because many women have chosen to remain silent, fearing they will be stigmatised by society if they speak out.

No witness protection

As the Bosnian war slips further into history, it is becoming more difficult than ever for some women to talk openly about their experiences, according to Nela Porobic from the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

"What we are finding from our discussions with victims of sexual violence but also with the professionals working with them is that talking about sexual violence was actually easier in the midst of war and immediately after the things happened rather than now, with the passage of 20 years," she says.

"They feel society is tired, they don't want to hear about what happened, they want to move on - but these women can't move on."

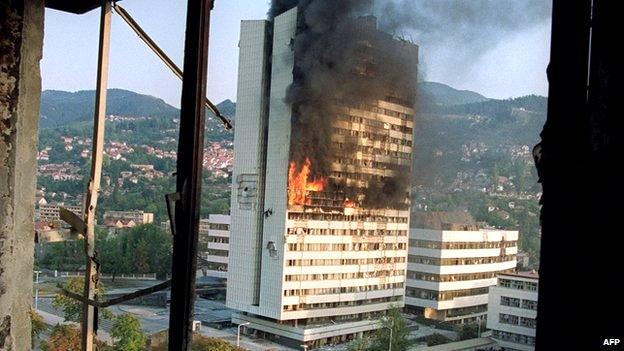

Civilians were often targeted in the Bosnian conflict

Researchers say the war in Bosnia created a "hierarchy of trauma". With so many atrocities committed between 1992 and 1995, sexual violence is viewed by some as a lesser evil than ethnic cleansing or torture.

For those seeking justice, the obstacles remain immense.

The courts are already trying to clear a backlog of some 1,300 war crimes cases. Only those cases regarded as the most serious, or involving high-ranking officers, are dealt with at the state level where witnesses are given anonymity and protection.

Cases involving women raped by rank-and-file soldiers are often passed to lower-level regional courts, where there is no witness-protection programme and victims may be asked to give evidence in front of their attacker.

'A shell of a man'

So far, there have been fewer than 70 prosecutions for crimes of sexual violence during the Bosnian War.

"Survivors of sexual violence feel that no one believes what happened to them," says Sabiha Husic, director of the Medica Zenica women's project.

"Most survivors tell me they don't want to go through with the legal process if it means they're going to have to give evidence to prove their case.

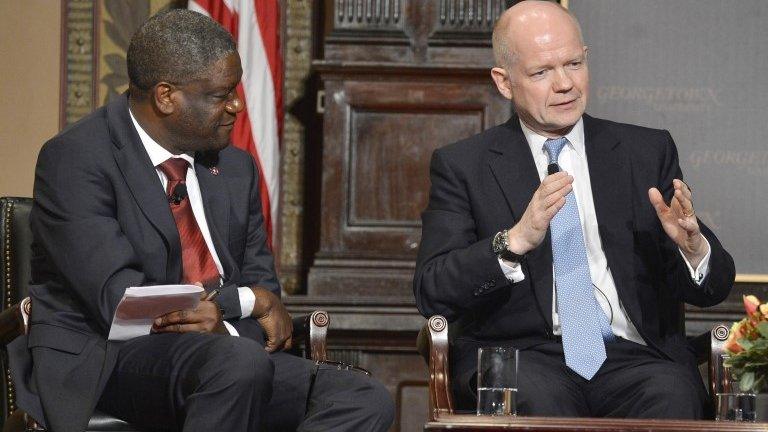

William Hague and Angelina Jolie are collaborating on a campaign to crack down on sexual violence in war

"We try to support and encourage them but sometimes when they are asked to appear in court, it's just too stressful and traumatic."

Men were also raped during the Bosnian War, often as a means of humiliation. Zihnija, a former soldier in the Bosnian army, shakes visibly as he recounts what happened to him.

"The military police took me to a basement and beat me unconscious," he recalls. "When I woke up, one of the officers took a shovel, ripped my trousers and put it inside me. Then they threw me back on the floor. They thought I would probably bleed to death.

"When you lose an arm of a leg you can see it - but when your soul is hurting it's invisible. I may look like a rock but I'm just a shell of a man. A shell."

Rapists still at large

The issue of sexual violence in conflict will be addressed at a major international conference in London in June, chaired by UK Foreign Secretary William Hague and the Hollywood actress and UNHCR special envoy Angelina Jolie.

The pair have been working together on the issue since Mr Hague watched Angelina Jolie's film about the Bosnian War, In The Land of Blood and Honey, two years ago. They travelled to Bosnia last week, and pledged to use the London summit to launch new guidance on documenting and investigating war zone rape and to increase the support given to survivors.

The war created a "hierarchy of trauma", researchers say, in which rape survivors have been overlooked

While better evidence-gathering may lead to more prosecutions in future conflicts, for some any improvements are already too late.

"The men who raped me are still at large," says one survivor, Edina, as Hague and Jolie toured the crumbling former UN peacekeeping compound in Srebrenica.

"I've found some of them on social networks. They walk around freely. They have Facebook profiles," she says. "I'm bitter towards the Bosnian government because the process of arresting and prosecuting the perpetrators is so slow. After 20 years, many victims have already died."

"They didn't live long enough to see justice being done." she says.

- Published26 February 2014

- Published29 May 2012