Ukraine-Russia gas row: Red bills and red rags

- Published

The political pressure is rising as the pipeline pressure falls

Ukraine says Russia has cut off gas supplies, in what is a major escalation of a dispute between the countries.

Gazprom, the Russian state energy firm, has pledged to continue supplies to Europe, but says it is Ukraine's responsibility to ensure gas flows through the country.

We examine what's behind the row, and its potential impact on Europe and its gas supplies.

What is the row about?

The immediate dispute is about Ukraine's unpaid gas bill to Russia. For months, Gazprom had threatened to halt supplies, only for Ukraine to make part payments just before the deadlines imposed by Russia.

However, it seems that Russia has lost patience. Gazprom has now in effect installed the world's largest pre-pay meter. It wants Ukraine's state-owned Naftogaz to pay upfront for its gas.

Gazprom says it is owed an immediate $1.95bn (£1.15bn) out of a total outstanding bill of $4.5bn.

Despite continuing talks in Brussels to try to resolve the dispute, Gazprom and Naftogaz have filed lawsuits against each other at the Stockholm arbitration institute.

Is this just about unpaid bills, or something more?

There is definitely a bigger picture. Lurking behind all this is the power struggle between the interim Ukrainian government, which leans towards the EU, and Russia, which wants to keep Ukraine firmly within its sphere of influence.

In February, months of street protests culminated in the removal from power of Ukraine's pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych. He had decided not to sign an association agreement with the EU, opting instead to join Russia's customs union.

But the interim government in Kiev has reversed course. In return, the EU is providing development assistance, a loan of 1.6bn euros (£1.3bn; $2.2bn), the temporary removal of customs duties on Ukrainian exports to the EU, and a programme to lessen Ukraine's energy dependence on Russia.

That angered the Kremlin, and Gazprom raised the price Ukraine would have to pay for its gas in future by 81%.

Previously, Ukraine's gas imports were subsidised in return for Russia's lease of the naval base at Sevastopol in Crimea, the home of the Russian Black Sea fleet. But since Russia annexed Crimea last month, that agreement is no longer valid.

Before Russia scraped the discount, Ukraine paid $268 per 1,000 cubic metres. The price now is $485.50 per 1,000 cubic metres, the highest in Europe.

Will anyone outside Ukraine be affected?

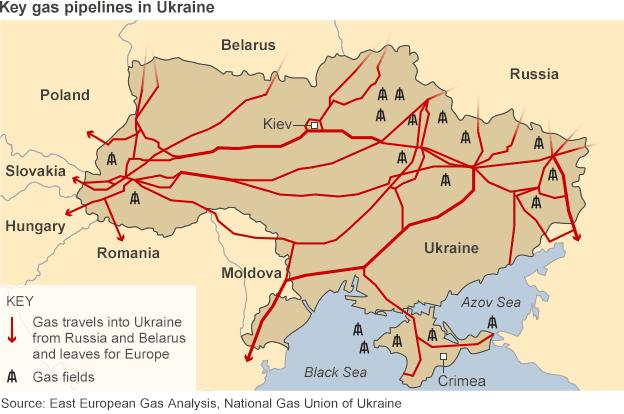

Quite possibly - the EU gets about a third of its gas from Russia, with some 50% of this flowing through Ukraine.

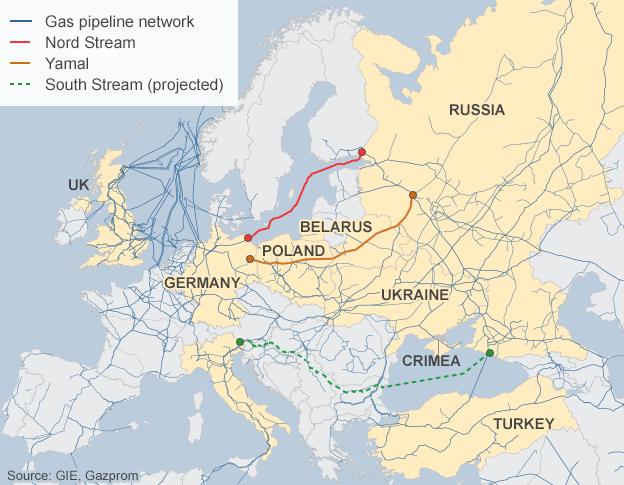

Outside Ukraine, two other pipelines link Russia to the EU: the North Stream (under the Baltic) and the Yamal, which flows through Belarus and Poland.

Germany and Italy are the two biggest customers for Russian gas. However, Germany is building more coal-fired power plants and renewable energy installations, including offshore wind farms.

Another pipeline, the South Stream, is under construction, running from Russia under the Black Sea to Bulgaria and then splitting into two branches, north through Hungary to Austria, and south to Italy. The project website says the South Stream is scheduled to begin supplying gas late next year and be completed in 2018-19, external.

However, Bulgaria has halted construction of its section of the pipeline, prompting Russia to accuse the European Union of imposing "creeping" economic sanctions.

Interconnectors between different pipelines could also help. South-eastern EU countries such as Austria and the Czech Republic receive their supplies via Ukraine and are most at risk if Russia turns off the taps. However, they could receive relief supplies via the interconnectors flowing down from Germany.

Other countries, such as Poland, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland, are looking to diversify their energy supplies, for example by bringing in more liquefied natural gas (LNG) from non-European countries, such as Qatar, or shale gas from North America.

One factor working in the favour of EU consumers is the weather: energy use falls in summer, reducing dependence on imports.

South Stream project website, external

Analysis from The Economist on reducing EU dependence on Russian gas, external

Reuters: EU imports from Russia could fall 25% by 2020, external

Hasn't Gazprom promised to maintain Europe's supplies through Ukraine?

It has, promising to supply Europe at "full volume". Gazprom added, though, that it was Ukraine's responsibility to ensure shipments passed through the country uninterrupted.

History suggests that Europe should remain cautious.

On New Year's Day 2006, Russia said it wanted to increase the Ukraine price per 1,000 cubic metres by more than 400%. When Ukraine said no, Russia turned off the country's supplies.

Within hours, other countries - including Austria, France, Germany and Italy - began reporting pressure drops in their pipelines of about 30%. The dispute was settled three days later, but prompted much nervousness in the EU about its dependence on Russian energy.

Three years later, again on New Year's Day, Russia again cut supplies. This was during a very cold spell, leaving countries such as Bulgaria and Slovakia with serious cuts to supplies. Industrial plants were shut down, while people struggled to heat homes and schools.

After more than two weeks of shortages, Russia and Ukraine reached an agreement that was supposed to run for 10 years.

Germany is Russia's biggest EU customer for gas but relations have turned distinctly frosty since the crisis in Ukraine erupted

How reliant is Ukraine on Russian gas?

Traditionally, more than 50% of Ukraine's gas needs have came from Russia, although the country has also been a big importer from Turkmenistan.

Last year, Gazprom exported about 26 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas to Ukraine, more than half the 50.4bcm it consumed.

Although Ukraine's nuclear and coal sectors produce more electricity than gas, the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES) says that "industry and municipal infrastructure are highly dependent on gas".

The OIES estimates that Ukraine's gas requirement for this year will be about 50bcm, with about 20bcm produced inside the country.

If the worst came to the worst, and Russia halted supplies, Ukraine would have to find alternative suppliers for some 30bcm.

Talks are under way within the EU about helping Ukraine in an emergency by sending gas via pipelines in Slovakia.

Surely, a serious cut in gas exports would also hurt Russia

Almost certainly.

The question is, would President Putin be prepared to suffer short-term pain for long-term gain (whatever that gain might be)?

The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies estimates that last year, 53% of Gazprom's export revenues - or $33.3bn - went through Ukraine.

Any escalation of the gas dispute could seriously dent Moscow's tax earnings.

It may also be a reputational disaster. Gazprom, and Russia generally, won't want to be known as an unreliable supplier.

That would curtail international investment in the country's oil and gas sectors, and spur on the West to find alternative sources of energy.

But, while the West might want to reduce its dependency on Russia, Moscow has showed it is capable of reducing dependency on the West. In May, President Putin signed a multi-billion dollar, 30-year gas and investment deal with China.

- Published1 May 2014

- Published13 November 2014

- Published23 April 2014

- Published24 March 2014