Anglo-Irish Bank: The background to Golden Circle deal

- Published

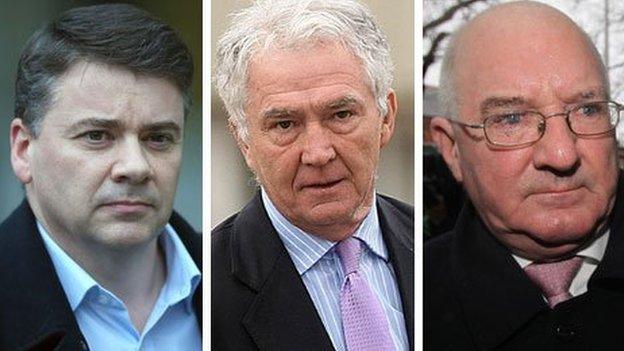

Pat Whelan, Sean FitzPatrick and Willie McAteer: Whelan and McAteer were found guilty of providing illegal loans to prop up the share price of the former Anglo Irish bank: Mr FitzPatrick, centre, was cleared of the charges

It was a Belfast judge who first called the 'Golden Circle' deal for what it was.

Back in 2011, Mr Justice Deeny heard a case involving a former Anglo Irish Bank client.

Part of the hearing touched upon the controversial transaction.

The judge was blunt in his assessment. The lending of money on favourable terms to buy shares in the bank was "improper and unlawful".

Almost exactly three years to the day, that view has been confirmed by a Dublin jury.

The Anglo bankers Pat Whelan and Wille McAteer were deeply involved in the nuts and bolts of that improper and unlawful deal.

Though for all that has been written about the greed, arrogance and recklessness of Anglo, this deal was more about survival than turning a profit.

Seán Quinn, then Ireland's richest man, had built a huge shadow holding in the bank.

Mr Quinn had used a financial product, known as a CFD, to effectively control about 25% of the bank's shares.

The CFD was really a highly leveraged bet that Anglo's share price would keep rising.

But the price was falling and Mr Quinn's losses were mounting.

When the bankers first learned about the size of the Quinn stake in 2007, they were horrified.

Having the fate of the bank tied so closely to one man, who was in danger of getting into big financial problems, would ruin its credibility with international investors and depositors.

As turbulence increased across the whole western financial system, the Quinn problem grew in urgency.

So there was undoubtedly relief, and probably some elation, when in July 2008, the deal was done to place a large chunk of the Quinn position with 10 loyal customers.

Those emotions may not have been explicitly shared by Ireland's financial regulators, but they knew exactly what was going on and approved of it.

Pat Whelan told the court that there seemed to be a "hotline" between the bank and the regulator, Patrick Neary.

And in many ways this case acts as a reminder, as if one was needed, of just how thoroughly Ireland's regulators and politicians were captured by the interests of finance in the run-up to the crash.

In his evidence, Mr Neary revealed a peculiar lack of curiosity for someone who was supposed to be acting as a watchdog.

He told how Seán Quinn fetched up unannounced to his office in January 2008 as market rumours swirled about the Quinn CFD.

Mr Neary didn't ask directly about the CFD, concluding that Mr Quinn's investments were his own business.

Ireland suffered from people like Mr Neary failing to ask the hard questions of people like Mr Quinn.

But this soft-touch regulation was the product of a political environment.

Look at CFDs, the tool Seán Quinn used to make his ruinous bet on the bank.

In 2006, the Irish tax authorities announced plans to apply stamp duty to CFDs - a tax which applied to normal share dealing.

Dublin's finance sector launched a furious lobbying operation and the plan was effectively killed off by Finance Minister Brian Cowen.

Mr Cowen later became Taoiseach (prime minister) and it was on his watch that the excesses of banking and finance finally sank the country's economy.

- Published11 April 2014