How France's National Front captured Henin-Beaumont

- Published

The Front could become France's largest party in the European election, some polls suggest

France's National Front is expected to score well in this month's European election, following a breakthrough at local polls in March. Henri Astier reports from Henin-Beaumont, its flagship municipality in the north, to examine whether its success there can be repeated nationally.

At the annual barbecue organised by the Henin-Beaumont shooting club, some are downing beers and others firing at clay pigeons. But the National Front (FN) activists who have come here have something else in their sights - potential supporters.

This is the kind of get-together they have attended for years.

"Whenever an association organises an event, we turn up to show that we support them in their activities. It enables us to be in touch with people and also have a good time!" Christopher Szczurek, a 28-year-old who looks after community links for the local FN, says in between kissing a dog and shaking hands.

Week in and week out, National Front teams have been working the crowd in fairs, markets, and car boot sales. Steeve Briois, the town's party leader, is regularly seen taking elderly ladies for a twirl in dance halls.

The National Front is connecting with Henin-Beaumont voters and their dependents

The efforts to connect with the people of Henin-Beaumont have been richly rewarded. At the recent municipal elections, the FN won more votes than all other parties put together, capturing the town in the first round.

This was quite a feat for a far-right party in a town that had been a socialist stronghold for 70 years. Mr Briois is now the most prominent among 11 new FN mayors across France.

The front's signature issues - such as security and immigration - have clearly struck a chord in Henin-Beaumont, and sympathisers are not hard to find at the barbecue.

"The housing estates are unsafe and I expect the Front to do something about it," says Romuald, 24, who like many supporters prefers not to give his full name.

Another shooting club member, 61-year-old Jean-Pierre, says: "I don't think I am being racist when I say that there may be rather too many immigrants. I live in an area where Roma people live in camps and we suffer thefts and poaching as a result. Enough is enough."

Rotten council

But to carry a left-wing mining town in a region ravaged by pit and factory closures, Mr Briois had to do more than beat the FN's traditional drum. He has soft-pedalled on ideology to emphasise practical support.

In every part of town FN representatives have been on hand to help residents with housing benefits and other services. "We have been elected because people know that we are accessible and there for them," says Ms Beigneux, 33, who is now in charge of social affairs at the town hall.

Such grassroots activism has been particularly effective as it stood in sharp contrast with the corruption and fecklessness of recent socialist administrations, argues Haydee Saberan, regional correspondent for Liberation newspaper.

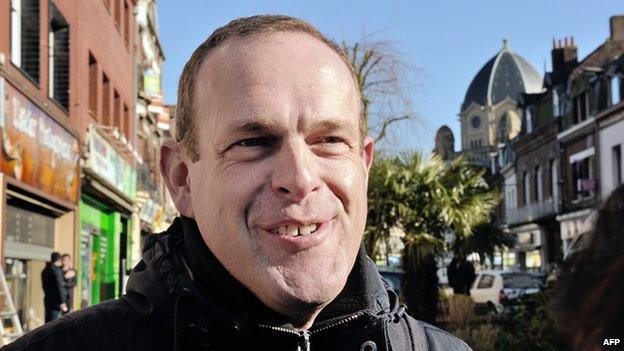

Steeve Briois is a close aide to FN leader Marine Le Pen

Ten years ago, the council was forced to almost double local tax rates in a failed attempt to fix local finances. "For the humble home-owners there, it was a disaster," says Ms Saberan, author of the book Bienvenue a Henin-Beaumont (Welcome to Henin-Beaumont).

The former mayor, who nearly bankrupted the town, was later jailed for embezzling public funds. He was succeeded by another socialist who was widely perceived as out of touch, says Ms Saberan.

All this has been a boon for the National Front. "We needed to change," says Maryline, 56. "I'm really happy that the FN won, with all the stuff that went before. The mayor helped himself and we were the ones who paid for all this. They didn't care about people."

Halal butchers are trading well and the town does not feel hostile to immigrants

Maryline is a care worker struggling to make ends meet on a 1,000-euro (£814) monthly salary. Like many other residents, she is pleased with Mr Briois's decision to cut local taxes by 10%. "That's a good start. It looks as though he's keeping his word," she says.

Even some socialists are willing to give the new mayor the benefit of the doubt. "I did not vote for him, but I'm keeping an open mind," says Francine, 79. "If he does well that's fine. If not, I'll complain."

Multiethnic far-right?

Making the FN brand appealing to Henin-Beaumont voters has meant muting the party's traditional anti-immigration message. Xenophobia, notes Octave Nitkowski, external, a prominent local blogger and author, does not sell well in a town built on wave after wave of foreign workers.

"First there were Belgians, then Italians, Poles, and North Africans. There are no separate communities. Everyone has mixed blood," says Mr Nitkowski - who himself has Polish, French and Arab ancestors. "That's why the front had to base its campaign on social issues."

Two months into the FN's rule, the town hardly feels hostile to migrants. In the central square, two halal butchers facing each other are doing brisk business. A headscarf-covered doll stares out of the window of an Islamic bookshop.

Several residents of foreign origin appear to be well disposed towards Mr Briois. "Whenever I've seen him he has treated me with respect and courtesy," an Algerian-born man says. "I won't turn my back on him now that he is mayor."

Shop owner Marie-Francoise Gonzalez is "appalled" by the FN's win

But for some in Henin-Beaumont, the new, inclusive image presented by the FN is only a facade.

Marie-Francoise Gonzalez. who runs a sandwich shop on the square, believes that although local FN have sanitised their language, they remain "fascist" at heart and their victory has encouraged prejudice among residents.

Racism is on the rise," she says. "I see it in my own shop: I hear things I haven't heard in 15 years! I am appalled."

The problem for the local left is that it is bleeding voters and that many are going over to the FN - not just in Henin Beaumont but across the region.

A retired dentist from neighbouring Billy-Montigny who describes himself as a lifelong socialist says he voted for FN for the first time in March. He is not alone. The national front leader there - who, tellingly, is a former communist - doubled his score in six years.

Henin model

Laurent Brice, the FN head for Pas-de-Calais area, says the party fielded candidates in 30 districts there in the municipal elections, up from just seven in 2008.

"People there are not afraid to stand under the FN banner," he notes. "This shows our strategy of putting down roots is working."

Could Henin-Beaumont provide a blueprint for success at national level? Mr Brice thinks so.

The Henin-Beaumont town hall was previously held by socialists for almost 70 years

"It is no accident that Steeve Briois has been appointed general secretary of the National Front, and is in charge of developing activist networks," he says.

As a senior aide to FN leader Marine Le Pen, Mr Briois has played a key role in detoxifying the brand nationwide.

But journalist Haydee Saberan doubts that Henin-Beaumont is necessarily a model for France at large.

Mr Briois' victory, she says, owes a lot to chance. His charisma, the implosion on the left and absence of the centre-right may be difficult to replicate elsewhere.

But that will not stop the FN trying to build on its local successes for the European elections. According to polls, what was once a fringe group may emerge as France's most popular party.

And the Front appears here to stay in Henin-Beaumont. "I believe they'll win again next time," resident Anne-Sophie Cailleaux - clearly not a supporter - says glumly.

- Published28 March 2014

- Published15 April 2014

- Published4 April 2014