Dublin-Monaghan: Ireland's unsolved bomb massacre 40 years on

- Published

The aftermath of the Talbot Street bombing in Dublin

Forty years ago this month, bombs in Dublin and Monaghan, in the Republic of Ireland, killed 33 people and an unborn child - it was the most deadly attack in the political violence known as the Troubles. Victims and relatives have just announced their intention to sue the British government.

No-one was ever charged in connection with the atrocities on 17 May 1974. Survivors and relatives of victims have never given up trying to find out the truth - with continuing allegations of collusion between the UVF militants responsible and elements of the British security and intelligence services.

Dublin city centre was busier than usual just before 17:30 that Friday evening. A bus strike meant the streets were packed with people travelling home on foot.

Derek Byrne was just 14 and only a week into his first job working as a petrol pump attendant. Just as he was filling a car with petrol, a huge explosion struck on Parnell Street. His injuries were so horrific that emergency services thought he had died. He recalls waking up in a hospital mortuary.

"I just remember pulling back the sheets and then the lady in the morgue, she ran out," he says.

"I don't know whether it was hospital porters or doctors who came in. I was put on a trolley and brought straight to theatre. I was 18 hours in theatre and then 12 weeks in a coma after that."

The scars of that day remain: "Only five weeks ago I got the all-clear to have surgery around the heart to remove shrapnel. I'm still waiting to get the shrapnel removed - they also found some in my arms and then in my knee and that has to be removed, they said."

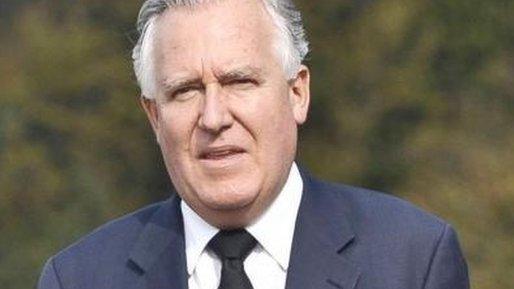

Derek Byrne today

Nearby, Bernie McNally was a 16-year old working in a shoe shop on Talbot Street. She heard the first bomb - before another huge blast outside. Two women she was talking to in the shop died.

"There was a big flash up in the sky and the bomb just exploded," she says.

"I was caught in the blast then. My friend May McKenna and a late-night shopper I went to get sandals for were killed. I got serious eye injuries and I eventually lost my right eye as a result of it. The devastation in the street was just unbelievable."

More died in a third bomb and another in Monaghan, 80 miles (129km) north. A monument on Talbot Street lists the victims - among them an entire family, an Italian man, a French Jewish woman whose family had survived the Holocaust, a World War One veteran and a pregnant woman.

Missing file

While Northern Ireland had been engulfed in violence since 1969, attacks by pro-British Loyalist militants south of the border where the anti-British IRA was active were very rare.

The 1974 Dublin and Monaghan bombs were the work of the Loyalist UVF - though this was not known until the group admitted responsibility in 1993 saying it was solely responsible, without any outside assistance.

Its statement gave no motive for the attack, though a former senior UVF member later said it was to "return the serve" in revenge for IRA violence in Northern Ireland.

Bernie McNally today

Mysteriously, back in 1974, police on both sides of the Irish border ended their investigations into the bombings within just months, with files going missing.

Persistent allegations of collusion between the killers and the British security and intelligence services have been made over the years. Former British military intelligence officer Colin Wallace, who served in Northern Ireland at the time, believes it is "inconceivable" that those involved were not under surveillance.

"A number of those involved were informants of the security services, who must have had advance warning," he says.

"There never has been a case before or since where Loyalist terrorists have been able to carry out bombings of such complexity. It's my belief that the explosives were supplied by the security forces or were recycled from explosives they'd captured."

Mr Wallace says that some of those responsible were allowed to continue operating as militants and were involved in other killings.

"The British Government spent millions on the Bloody Sunday inquiry, but there was much greater loss of life here while there has been a complete apparent lack of interest in finding out what happened," he says.

"In 1984, along with Captain Fred Holroyd, I sent a complete file to [then Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher - which then went missing. This is a jar of worms which nobody wants to open up - because it will reveal why these people who were connected to other killings were allowed to roam free for so long."

While some suspects have died, several are still living in Northern Ireland and elsewhere in the UK.

'Something sinister'

The British government has refused to address the allegations in full - for reasons of national security and to protect informants.

Former Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern set up two judicial inquiries into the bombings. One, by the late Justice Henry Barron, was denied access to British intelligence files on grounds of national security.

"We tried everything we could and I tried every way I could to get [then British Prime Minister] Tony Blair to... get the authorities to release those files," Mr Ahern told the BBC.

"We got a lot of information, it's true to say, and we got a lot of co-operation but that remains an outstanding issue.

He said there was still widespread suspicion of "collaboration" and "a cosy relationship" between Loyalist groups and British security forces, and that until those files were seen, "it's neither fanciful or absurd to believe that there is something sinister in it".

Back in Talbot Street, beside the monument, survivor Bernie McNally says she never believed she would still be searching for answers 40 years on.

"It's so important to get answers for all the families, particularly for those who lost their loved ones," she says. "You need to find answers. I was blessed and I have a life, I was lucky enough to survive it but I think for all those who didn't survive, answers need to be given."

For more on this story, listen to BBC Radio 4's World Tonight programme at 22:00 (21:00 GMT) on 14 May.

- Published30 April 2014

- Published7 April 2014