Cameron's allies against Juncker fall away

- Published

- comments

David Cameron opposes Mr Juncker's instincts for closer ties with Europe

A senior British diplomat has said David Cameron , externalwill "not row back", that he will fight on to prevent Jean-Claude Juncker becoming head of the European Commission.

But even as British officials were saying the prime minister would insist on a vote at the summit on Friday, some of David Cameron's potential allies were falling away. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte said: "If an explicit vote is called for, we will support Juncker's candidacy... we will not block it."

Another member of the so-called reform camp, Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt, said that if Mr Juncker attracted a qualified majority of the heads of government, including support from the European Parliament, then Sweden would join the majority.

Only two weeks ago Prime Minister Reinfeldt was declaring his opposition to the process by which the candidate of the largest grouping in the European Parliament became Commission president. He opposed the fact that only Mr Juncker's name had been put forward because it excluded the names of others.

So what has happened? Countries and leaders with genuine concerns about both Juncker the man and the process by which he was selected do not want to stand against the majority.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel told the Bundestag it would be no "tragedy" if Mr Juncker was elected by a qualified majority. In the past the EU president has been elected unanimously.

The British Prime Minister does not back Mr Juncker for the role, as the BBC's Europe editor Gavin Hewitt reports

What none of these leaders are saying is that Mr Juncker is the best person for such an important and high-profile post or that they agree that the biggest bloc in the European Parliament essentially gets to chose the Commission president. Even in Brussels those doubts are widespread but in the end leaders do not want to be accused of defying the voters.

Even though only 9.7% of the European electorate - according to one estimate - voted for centre-right parties backing Mr Juncker's candidacy, most MEPs insist that the former Luxembourg prime minister has a democratic mandate.

It also weighs heavily on the leaders that the parliament almost certainly would reject any other candidate and that would lead to institutional paralysis.

Outmanoeuvred

So we are left with a British prime minister fighting on - with perhaps only the Hungarians as an ally - defending a principle he insists is widely supported. He believes that allowing the parliament to select who leads the Commission is not in line with the treaties. He says that it changes the institutional balance by the back door. He thinks it is "profoundly wrong" and carries the risk of politicising the Commission.

It is one of the great unanswered questions in this drama: how did it end up with so many leaders agreeing to a candidate and a process which they do not believe in? How did it get this far? How were the leaders so outmanoeuvred by the parliament?

Jean-Claude Juncker is confident he will become the next EC president if "common sense prevails"

Ironically, even as the 11th hour approaches, increasing doubts about Mr Juncker are appearing in the German and European press. Questions are being raised about the fees he receives for addressing executives. Friends of Mr Juncker insist he has broken no rules, but Bild magazine says he "wants to say only the bare essentials about his well remunerated speeches. That might work in his home country of Luxembourg which is famous for its banking secrecy, but not in Brussels".

The deputy economics editor of the French paper La Tribune says that Mr Juncker "does not embody the renewal Europeans yearn for".

So what happens next? There are strong hints from the Germans that Mr Juncker will embrace much of Mr Cameron's reform agenda and will try to talk to him. The UK may be offered a consolation prize with the next British commissioner taking a top economic post. Even though the prime minister will not take Mr Juncker's call at the moment, he most probably will in the future.

Mrs Merkel, Mr Rutte and the Swedish prime minister have reiterated their support for Britain's continued membership of a reformed European Union. In truth, bigger battles lie ahead.

There is, of course, an element of domestic politics at play with David Cameron's strategy. Facing down the lacklustre Mr Juncker seems to be playing well with British voters. It is certain that come the UK's national election, potential UKIP voters will be reminded of the PM's lone stand in Brussels.

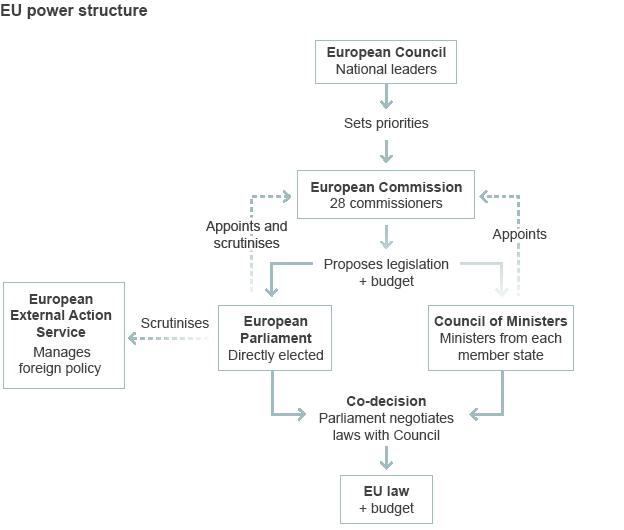

But David Cameron is also fighting for a principle that nominating Mr Juncker would be an "irreversible step which would hand power from the European Council [heads of state and government] to the European Parliament". Why does that matter? Because the prime minister in his bid to sell a reformed Europe to the British public needs the reverse to happen: a shift in power back to national parliaments.

This fight over the former prime minister of Luxembourg is part of the longer struggle to reform the EU.