In pictures: Rounding-up of wild horses in Galicia, Spain

- Published

Every year, crowds flock to the Spanish village of Sabucedo, for a tradition that dates back to ancient times - cutting the manes and tails of the wild horses that live in the mountains of Galicia in north-west Spain.

The origins of the ritual are unclear but according to legend, the rite dates back to the 16th Century when the people of the village were spared the plague by their patron saint Lorenzo and in return sent horses into the wild.

But the undoubted drama of the "Rapa des Bestas" is to animal rights activists a show of unnecessary brutality.

Pictures by Daniel Rodrigues.

At 06:30 on a July morning, some 100 people - fathers, sons and friends - gather in Sabucedo. Prayers are said and they head for the hills in search of the "beasts". Fog hampers the search as they cover long distances across breathtaking landscape looking for the horses.

A severe winter with torrential rain and freezing temperatures has hit the wild horses of Galicia hard.

Riders join the hunt to corral the horses together and bring them down from the hills.

The wild horses are known in Galicia as "brutes" and, as the round-up gathers pace, some of the horses struggle with each other. The clashes can sometimes turn violent.

Young and old take part in the search and when they feel they have rounded up as many horses as possible, they had back down the mountain to Sabucedo.

Tourists stand on the mountainside to watch the men and horses return.

The horses are driven down the main street in the village. Their final destination is the Curro, a circular pen that resembles a gladiatorial arena. The aim will be to force the horses, as many as 200 in number, to lie still on the ground for their manes and tails to be cut.

There are clear parallels with Spain's historical passion for bullfighting and the round-up tradition is popular throughout the Galicia region. However, the Sabucedo festival, which last four days, is the most popular and the most spectacular.

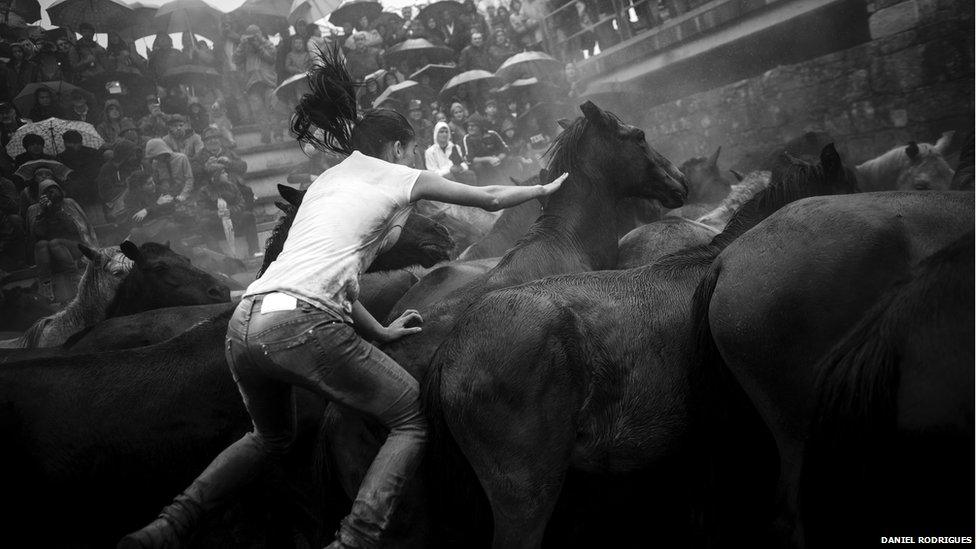

For up to two hours, a team from the village struggles with the horses in the Curro. It takes years of practice for the men and women of Sabucedo to work out how to overpower the wild horses. The children of the village look on because one day they, too, will take part.

The villagers reject the complaints of activists who condemn the brutality of the round-up. They argue part of the tradition now involves vaccination against diseases that the horses can pick up on the mountain.

Conditions inside the arena are crowded. Visitors to the village are only allowed to watch from outside the pen, because of the potential hazards.

Critics say that the act of wrestling the horses to the ground distresses the animals. Fights between the horses are not uncommon.

Legend has it that the strongest horses are considered sacred. So their ears are cut by villagers to differentiate them from the other animals.

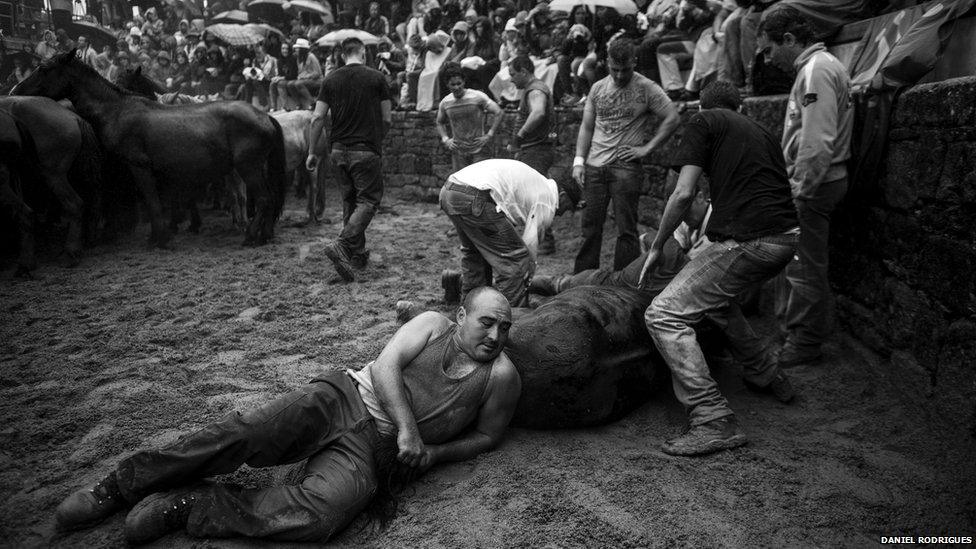

Once they are brought to the ground, the horses' manes and tails are cut. Four men are usually needed for the task: two to hold the horse's head, one for the tail and a fourth who cuts the mane and tail with scissors.

Rain and mud played a significant role in this year's round-up, which is rare even for this verdant region of Spain. By the end, the villagers are exhausted and the horses return to the mountains for another year.