Ireland confronts past treatment of unmarried mothers

- Published

Bessborough House, where this photo was taken, was closed in the 1950s on a doctor's orders because so many babies were dying there

The Republic of Ireland is to investigate the homes for children born outside marriage and their mothers, run by religious institutions for most of the last century. It follows concerns over the deaths of almost 800 children at a convent-run mother-and-baby home in Galway over several decades and controversy about whether they were given proper burials.

The BBC's Fergal Keane considers what the inquiry might mean for survivors, and for Ireland.

Growing up in Cork, I was acutely aware of the stigma attached to unmarried motherhood. What teenager in Ireland could avoid the shame attached to pregnancy outside marriage? It was the dreaded scenario in all our minds, but for girls it could mean banishment and anguish.

This photo shows Teri Harrison aged 18, when she was taken to Bessborough House

In 1973, the same year that I moved to the Cork suburb of Blackrock, a young Dublin woman was driven through the gates of a large house about 10 minutes from where I lived. Teri Harrison was 18 years old and arrived at Bessborough House heavily pregnant.

In the language of the time her child was "illegitimate". The choice for an unmarried mother usually fell between giving the child up for adoption or taking the boat to England for an abortion. Secrecy was paramount.

Teri says that at Bessborough, and in another church home where she finally gave birth, she was stigmatised.

"Do you know the one thing that got to most of us, was the times they would say to you: 'You're here because nobody wants you. You're here because nobody cares about you. You're here because you have sinned.'"

This photo from the 1950s (courtesy of Brian Lockier) shows a nun and children at the Sean Ross Abbey - one of the institutions likely to be covered by the inquiry

Some nuns feel their efforts to help the children in their care have been forgotten

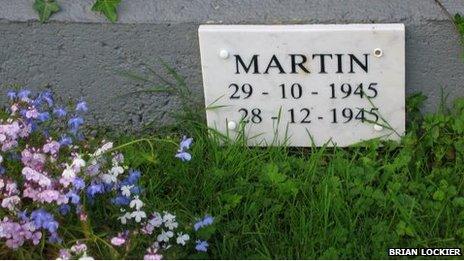

This baby was buried in a marked grave but many more were interred with no headstone

'Black pit'

Thousands of babies were adopted over the decades from the network of mother-and-baby homes operated by the Catholic religious orders. A much smaller number of Protestant-run homes may also come under the focus of the inquiry.

From the Catholic homes, hundreds of babies were sent to America, with allegations of children being trafficked to wealthy Catholic families seeking white children.

In Teri's case, her son was adopted at three months by an Irish family. She claims that she did not give her permission .

"He vanished into a black pit. Just a black pit. It's like… it's like his life was stolen and mine… I had three beautiful children after him. They are all adults now with their own children. And I look at them and I say: 'He should be here.' His birthday is every October on the 15th. He was born at 6.30 in the morning, he weighed 6lb 6oz (2.9kg) and he was beautiful. He was beautiful."

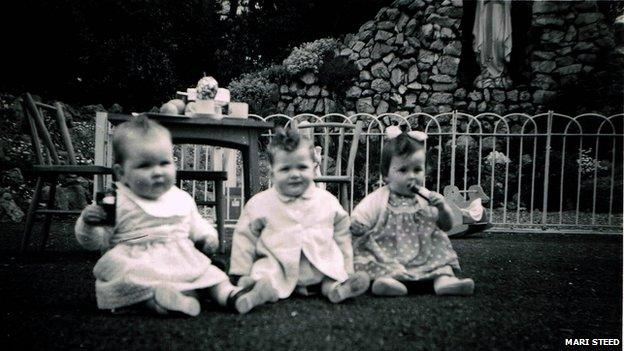

Many children were given up for adoption - some in Ireland, some bound for the United States

After decades of silence around the issue of unmarried mothers, Ireland is confronting the pain that touches families across the country.

Helen Murphy was adopted from Bessborough in 1962 and spent years trying to find her birth mother. Her own childhood was happy but she was conscious of an untold narrative in her past.

After finally discovering the identity of her birth mother, she found out that the woman had died three weeks previously. Her birth sister told her how her mother had wandered the streets of Cork trying to find her.

Helen explained: "There was this yearning in her to find her child. So I suppose she always knew she wasn't going to find me, somewhere deep inside. But she was looking for somebody who looked like the baby she had given up. I don't know because I've never been able to ask her: 'Did you really believe that you'd see me?'"

Some of the issues the commission of inquiry may look at include:

The high mortality rates in mother-and-baby homes: Bessborough was closed for a period in the 1950s by public health authorities because of concerns over the health of babies

The circumstances and location of the burial of babies who died in the homes

The use of infants in clinical drugs trials at some homes: Glaxo Smith Kline, whose predecessors ran the trials, has promised full co-operation with any inquiry

The number and manner of adoptions from the homes: thousands were adopted and hundreds were sent to America. The inquiry will want to know whether legal guidelines were followed

Among defenders of the Catholic institutions, there is a feeling that the good work done by religious orders has been forgotten in a rush to expose and condemn.

A former Mother Superior at Bessborough, Sister Sarto Harney, said there had been good staff at the home who had done their best to help the girls who came there.

Teri Harrison feels her son's life was stolen, as was her own

"I don't think it's fair… I think it's sad that is has come to this. We gave our lives to looking after the girls and we're certainly not appreciated for doing it."

Ireland has seen a plethora of inquiries over the last two decades from political corruption to sexual abuse in church run institutions. There is a certain weariness among the public at the prospect of more revelations. However, human rights campaigners, as well as the survivors of the institutions, believe the past cannot simply be pushed away.

Mairead Enright of the Faculty of Law at the University of Kent said the inquiry could help to create a new Ireland in which the attitudes of shame and exclusion could never again be fostered.

"There are plenty people in Ireland not much older than me who remember girls who were sitting next to them in school who weren't there the next day because they'd gotten pregnant and they'd been shipped off somewhere," she said.

"These homes were still operating in the 80s and 90s and it is faintly ridiculous to talk about the whole operation of the mother-and-baby homes in the past. That continues.

"It has had influence in families, it has had influence in how parents raised their daughters, in how women were perceived and how women conducted themselves, and it's also a set of issues that needs to be addressed in the present."

- Published23 June 2014

- Published8 June 2014

- Published5 June 2014