MH17 plane crash: Can Russia be blamed for Ukraine rebels?

- Published

Russia has denied responsibility for the actions of the rebels

The US has repeatedly accused Russia of backing rebels in Ukraine, saying the Russian government "created the conditions" that led to the MH17 disaster. Can Russia be held legally accountable for the actions of the rebels?

If it is proved that the rebels shot down the Malaysia Airlines plane, Russia will have some serious questions to answer.

It is alleged to have armed, trained and funded the separatists. But is this enough to establish Russia's legal responsibility?

In international law, there are two classic cases that have dealt with the issue of state responsibility for the actions of armed rebels in another country.

The cases pushed the law in dramatically different directions.

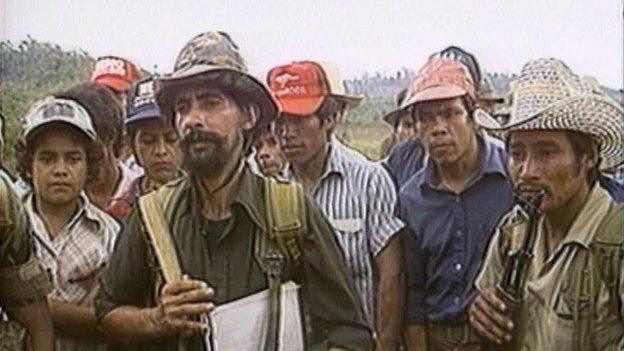

The Nicaragua Case, 1986

The US was not responsible for the Nicaraguan Contras, despite funding and arming them

Nicaragua sued the US at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the mid-1980s for supporting the Contras, a rebel group attempting to overthrow the left-wing Sandinista government.

The court did not doubt that the US had supported the Contras, or that the Contras had committed war crimes.

But the court ruled in its 1986 judgment, external that the US could not be held responsible for the Contras' crimes.

"The Court has taken the view that United States participation, even if preponderant or decisive, in the financing, organising, training, supplying and equipping of the Contras... is still insufficient in itself... for the purpose of attributing to the United States the acts committed by the Contras," it said.

This became known as the "effective control" test, and sets a high threshold for state responsibility.

Under this test, Russian President Vladimir Putin and his government would have little to worry about in the unlikely event of them being hauled before a tribunal.

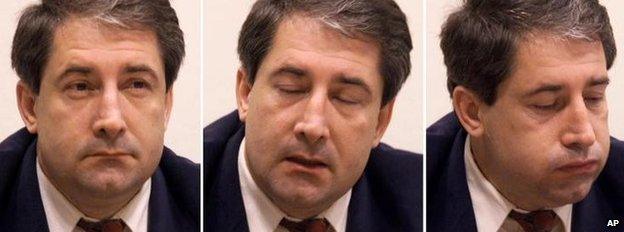

The Tadic Case, 1999

Dusko Tadic was convicted of war crimes in a long running series of trials and appeals

A decade later, judges at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia took a very different view.

The tribunal had to decide whether the Yugoslav government could be held responsible for the Bosnian Serb forces fighting in Bosnia.

"The control required by international law may be deemed to exist when the state has a role in organising, co-ordinating or planning the military actions of a military group," the court said in its 1999 sentencing of Bosnian Serb Dusko Tadic, external.

"Acts performed by the group or members thereof may be regarded as acts of de-facto state organs regardless of any specific instruction by the controlling state."

This became known as the "overall control" test, and set a much lower threshold than in the Nicaragua case.

Russian officials would find it difficult to avoid responsibility under this test.

Academic literature has mushroomed around the cases, and particularly these two opposing viewpoints.

Humanitarian groups much prefer the second test, governments are generally more comfortable with the first.

International law is often defined by its pliability.

As a result, the plausible deniability Russia has practised in its diplomacy may serve it just as well in the legal arena.