Nato faces up to crises on its borders

- Published

More than 2,600 civilians and combatants have been killed since the Ukraine crisis erupted

Nato leaders meet for their summit in Wales amidst the most serious security crisis in Europe since the end of the Cold War.

Russia is back at the top of Nato's agenda. And this summit must seek to respond to the long-term challenge from Moscow while managing the evolving drama on the alliance's borders.

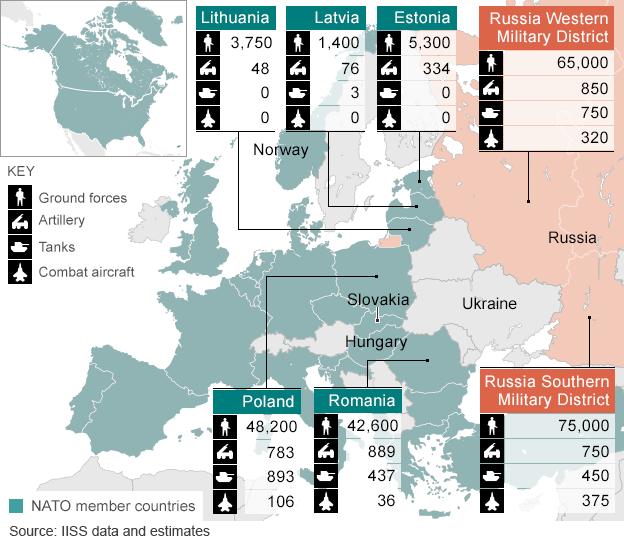

Nato has no doubts as to what is going on in eastern Ukraine. It insists that Russia's efforts to destabilise the country have gone way beyond simply arming separatist rebels. Russian units have been massed on the Ukrainian border.

And Nato analysts believe that significant numbers of Russian troops have actually moved across the border to operate inside Ukraine itself. The result - a series of significant reverses for the Ukrainian military.

So what is the impact on Nato? What might the alliance do? And what practically can it do to counter the chill wind coming from Moscow?

Western countries accuse Russia of much deeper involvement in eastern Ukraine than it admits

The challenge from Moscow is two-fold.

Russia is, firstly, overturning the post-Cold War security order in Europe; the vision of a new way of doing things set out most eloquently in the Nato-Russia Founding Act of 1997.

This document, signed in Paris by Nato leaders and President Boris Yeltsin, set out to build "a lasting and inclusive peace in the Euro-Atlantic Area".

It contained an explicit requirement to respect the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all states. Nato's view is that Russia's behaviour in Ukraine is a blatant breach of the principles contained in the Founding Act.

Secondly, Russia willingness to back separatist forces and to effectively nibble away at the territory of countries that used to be part of the Soviet Union - from Georgia to Ukraine - has revived fears among Nato members which border Russia, especially Poland and the Baltic republics.

Stirring wasps' nest?

So the principal task of this summit is to try to reassure worried Nato members and to send clear signals to Moscow about Nato's resolve. Nato already has significant rapid reaction forces. But these will be recast and their readiness improved.

A whole variety of steps will be taken under the heading of a Readiness Action Plan, the most striking of which will be a new multinational force capable of deploying to a threatened Nato country within 48 hours.

There will be a new headquarters further east - in Poland - and fuel, ammunition and other equipment will be pre-positioned. Facilities at Baltic and Polish air bases could be improved. This will all be bolstered by additional exercises.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has shown no sign of changing course so far

So much for reassuring allies. The Ukrainian president will meet Nato leaders, the only partner country afforded this privilege, in what is again a clear signal to Moscow. Nato's ties with Georgia will be stepped up to bring this aspiring member ever closer to the alliance. None of this will go down well in Moscow.

Some may applaud these steps as just sufficient to respond to Russia's overturning of international norms. But critics may argue that all this represents is the diplomatic equivalent of putting a stick into a wasps' nest and stirring it around.

Nato insists that it is not establishing new permanent bases closer to Russian soil (and thus it, unlike Moscow, is respecting the Nato-Russia Founding Act).

However, that is not going to cut much ice with the Russians who have already signalled that a movement of Nato forces eastwards will be met by a change to Russia's own military planning.

Economic sanctions have not changed Russian President's Vladimir Putin's mind and it is unlikely that Nato's new deployments will make him rethink his Ukraine policy either.

The rise of Islamic State has triggered a refugee crisis and will also be on the agenda at the summit

Arc of crisis

Of course Ukraine is not the only crisis acting as a backdrop to this summit.

The growing threat of instability in the Middle East will also be discussed; the murder of two Western journalists by Islamic State (IS) - a brutal jihadist movement that encompasses a large swathe of territory in both Iraq and Syria - highlighting the proximity of the arc of crisis stretching out towards Nato's borders.

Here too it is easier to describe the threat than to determine what to do about it.

This will not be a Nato matter as such but will figure prominently in informal discussions among the leaders, with President Barack Obama eager to sound out those governments who might be willing to join in further concerted action against IS.

Nato is however emphasising that the revamping of its reaction forces is not solely related to Ukraine and is equally applicable to the growing threats from elsewhere.

Nato could again offer training to Iraqi forces, though there would have to be a specific request from Baghdad.

There is though a great danger of overstating the nature of the threats posed by a resurgent Russia and even the barbarism of IS.

What promised to be a bland Nato summit focusing on what the alliance would do to in the wake of its withdrawal from Afghanistan has been transformed, and in the process Nato has acquired a refreshed raison d'etre.

But a resurgent Russia is not the Soviet Union Mark II. IS is unpleasant and a very real threat to the stability of several Middle Eastern states. But it is far from clear that Nato's military might is the most relevant Western response to the fears that it raises.

The summit will restate the allies' commitment to the future security of Afghanistan, though any green light for the new training and support mission there will depend upon obtaining the necessary legal agreements with the authorities in Kabul. And they must wait until a new president is elected there.

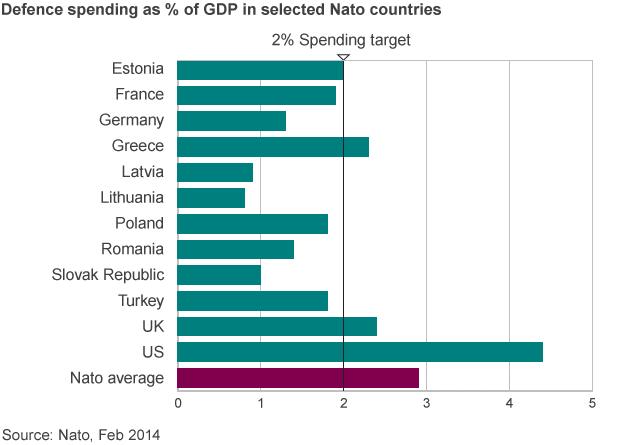

It will also inevitably touch on one of the thorniest issues that has dogged Nato's history - burden sharing.

Put simply, the US has always shouldered the lion's share of defence expenditure and has been more and more vocal in demanding that its European allies do more.

There is clearly an aspiration for countries to spend more of their GDP on defence, especially as their economies improve.

How specific such a commitment will be though is as yet unclear. But more capable, more deployable forces come with a hefty price tag.

Nato, according to its Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen, "needs to spend the right amount of money on the right things."